14 ways this powerful Ancient Egyptian woman used genderbending to become a female pharaoh, as revealed in Kara Cooney’s “The Woman Who Would Be King.”

Ancient Egypt wasn’t a bad place or time to be a woman. They had a surprising amount of rights and freedom — even to become pharaoh, like Hatshepsut.

Everyone knows all about Cleopatra, the clever seductress of two powerful Roman men who ruled over Ancient Egypt.

But without her forebear Hatshepsut, there might never have been a Cleopatra. Surely Cleopatra looked upon the woman who rose to the upper echelon of power as a true inspiration.

What made Hatshepsut’s success all the more remarkable was how unprecedented it was. Sadly, for the most part, feminism hasn’t progressed beyond the traditional patriarchy over the past few millennia. Case in point, the United States has yet to elect a woman as president.

In the ancient world, having a woman at the top of the political pyramid was practically unheard of. Patriarchal systems ruled the day, and royal wives, sisters, and daughters served as members of the king’s harem or as important priestesses in his temples, not as political leaders. Throughout the Mediterranean and northwest Asia, female leadership was perceived with suspicion, if not outright aversion.

–Kara Cooney, “The Woman Who Would Be King: Hatshepsut’s Rise to Power in Ancient Egypt”

LEARN 9 FASCINATING FACTS about Hatshepsut’s early life here.

In terms of the ancient world, Hatshepset truly was a remarkable woman. As our guide Mamduh mused, “They should make a movie about her — maybe many movies.”

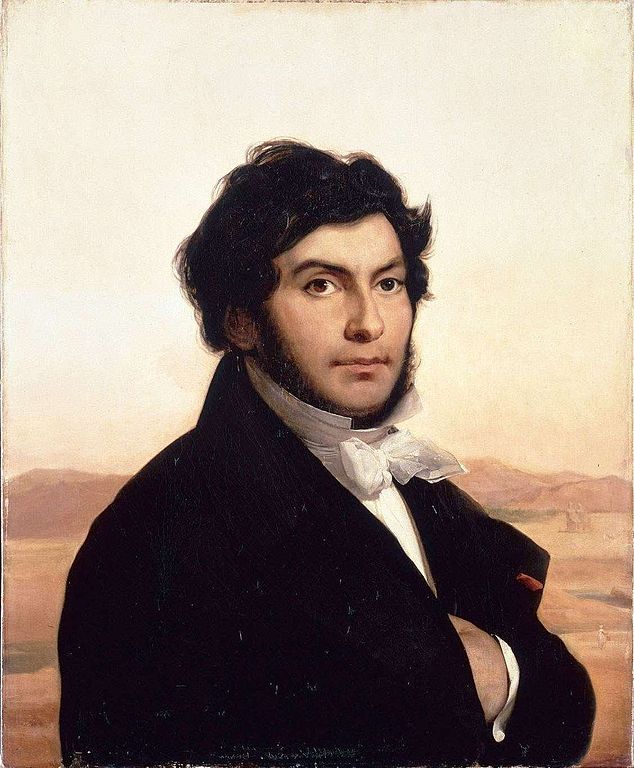

Thank Sobek for Jean-François Champollion! He was the first to find references to our remarkable pharaoh in the modern era.

“History records only one female ruler who successfully negotiated a systematic rise to power — without assassinations or coups — during a time of peace, who formally labeled herself with the highest position known in government, and who ruled for a significant stretch of time: Hatshepsut,” writes Kara Cooney in The Woman Who Would Be King.

During her prosperous reign, gold, cedar, ebony and other goods flowed through Egypt, and the temples, shrines and obelisks raised in her name were so impressive that later pharaohs endeavored to be buried nearby, creating the Valley of the Kings.

Incidentally, we have French archaeologist Jean-François Champollion to thank for rediscovering the first hints of Hatshepset’s existence in 1928 — apparently, deciphering the Rosetta Stone wasn’t enough of a claim to fame.

“Even Hatshepsut must have felt that her cross-dressing image was a bit too shocking for the time. ”

So how exactly did Hatshepsut move beyond being a queen regent to divine ruler? I do wonder how she viewed herself — could she be the first trans leader in history?

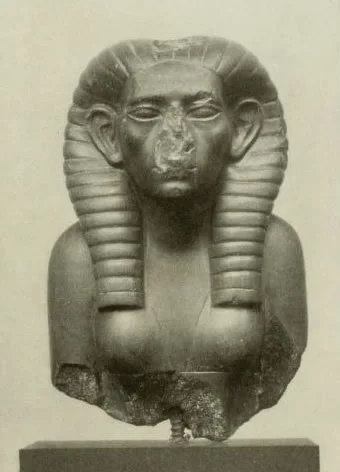

The loss of a nose makes this statue of Egypt’s first female king, Sobeknefru, a bit too creepy.

1. There was actually a female king of Egypt before Hatshepsut.

Just like Cleopatra, Hatshepsut had a role model from the past. Sobeknefru, daughter of Pharaoh Amenemhat III of the Twelfth Dynasty, ruled Egypt around 1800 BCE — about three centuries before Hatshepsut was born.

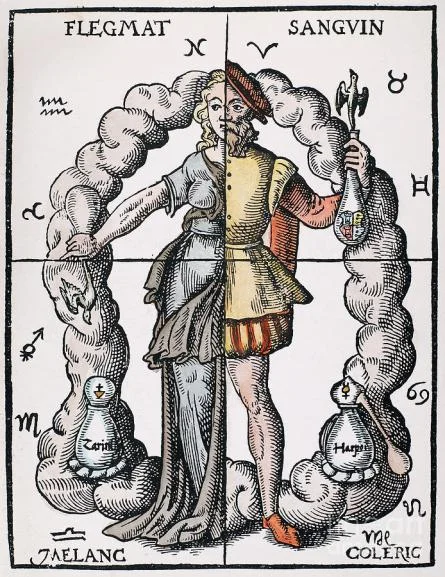

2. There wasn’t even a proper word for queen — so Sobeknefru blended masculine and feminine iconography.

The queens of Ancient Egypt were known as hemt neswt, or wife of the king — “a title with no implications of rule or power in its own right, only a description of a woman’s connection to the king as husband,” Cooney writes. To truly be seen as the ultimate ruler of the country, Sobeknefru had to take on the masculine title of “king.”

“Clothing was more problematic,” Cooney continues, “and Sobeknefru depicted herself wearing not only the masculine headdress of kingship but also the male royal kilt over the dress garments of a royal wife.”

THE FIRST FEMALE KING OF EGYPT, Sobeknefru, was named for the crocodile god, Sobek.

Learn more about his worship from our post on the temple of Kom Ombo.

3. A title shift on Hatshepsut’s monuments at Karnak might be the first clue of her massive ambitions.

A few years before she even became king, Hatshepsut dropped the title of God’s Wife, opting instead for the title of King’s Eldest Daughter. While the role of high priestess was one of the most powerful in Ancient Egypt, the adoption of this new title set the stage for a legitimate claim to the throne.

“Some Egyptologists see this rejiggering of her personal relationships as the crux of her power grab, a shift that moved her from a queen’s role to an heir’s, as the rightful offspring of Thutmose I and one who could make a heritable claim to the throne despite her female gender,” Cooney writes.

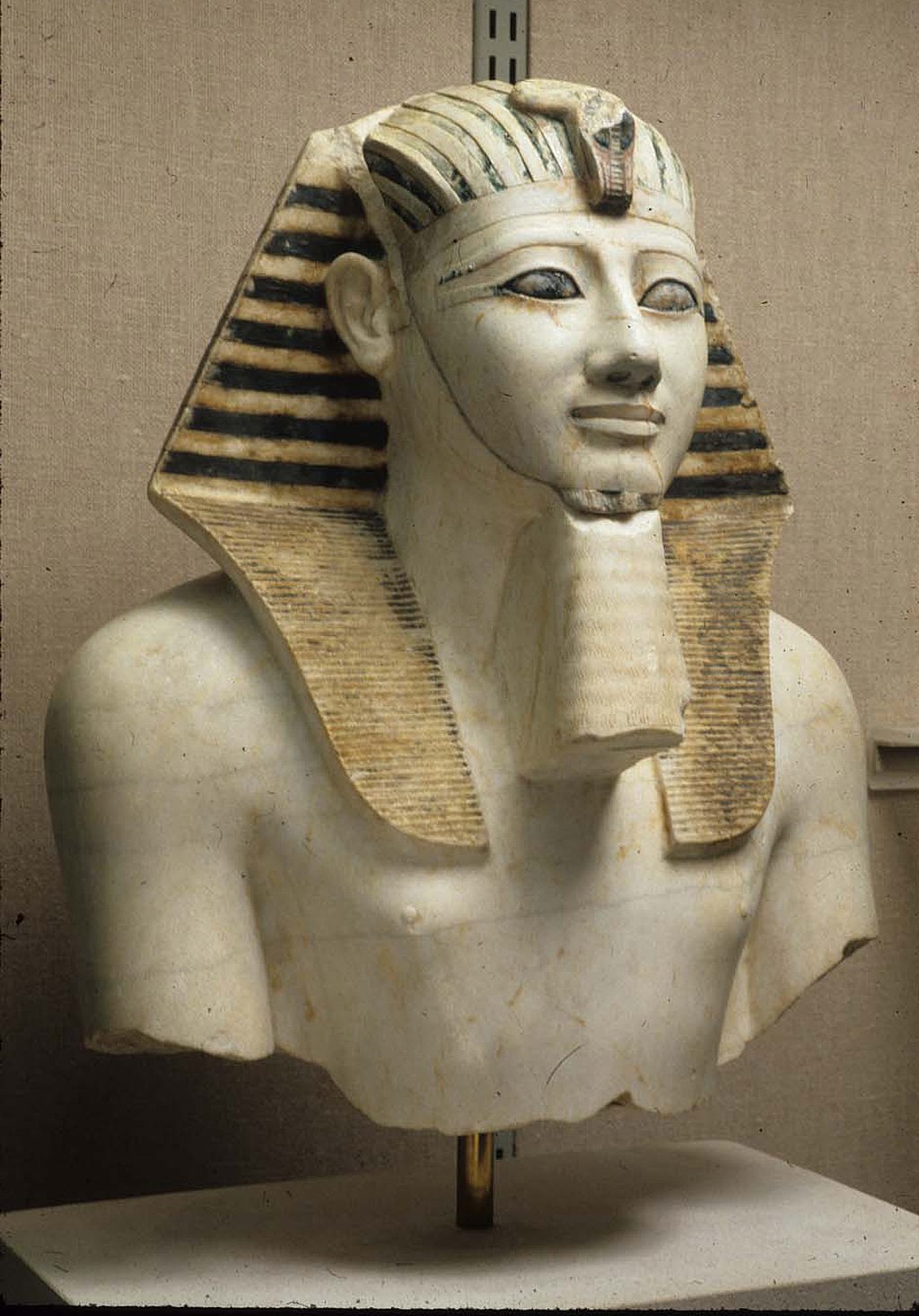

4. Like Sobeknefru before her, Hatshepsut reinvented her image as a nonbinary gender.

Another section at Karnak, the most massive temple complex of the day, in the royal city of Thebes, present-day Luxor, depicts Hatshepsut in men’s garments along with women’s.

The block “shows Hatshepsut wearing the gown of a queen on her body but the crown of a king upon her head,” Cooney writes. “The atef crown — a fabulous and extravagant amalgamation of ram’s horns and tall double plumes — was depicted atop her short masculine wig, probably to the shock of the craftsmen in charge of cutting the decoration. It was a confusing image for the Egyptian viewer to digest: a female king performing royal duties, offering jars of wine directly to the god, and all before any official coronation.”

5. She also took on a throne name, a privilege reserved for kings — again, before she was even crowned.

In the text on the same monument at Karnak, Hatshepsut called herself the One of the Sedge and of the Bee, which is translated as King of Upper and Lower Egypt.

What’s more, she introduced a throne name, Maatkare, The Soul of Re Is Truth. This act was “inconceivable,” according to Cooney. “Hatshepsut was transforming her role into a strange hybrid of rule ordained before it had officially happened,” she writes.

Part of her throne name is the goddess of truth and justice, “implying that at the heart of the sun god’s power was a feminine entity, Ma’at, the source that was believed to keep the cosmos straight and true,” Cooney writes, continuing, “Hatshepsut’s throne name communicated to her people that her kingship was undoubtedly feminine, and that feminine justice was necessary to maintain life with proper order, judgment, and continuance.”

6. About nine years into Thutmose III’s reign, Hatshepsut was crowned pharaoh — meaning there were two kings simultaneously on the throne.

When Hatshepsut was about 24 years old, in 1478 BCE, “the impossible happened,” as Cooney states. Thutmose III might have been a child, but he was still officially the king. Yet Hatshepsut, that wonderful feminist icon, decided to stop being the queen regent and that she would share the throne with her young nephew.

In this carving from her funerary temple, Hatshepsut is shown as a male, wearing the false beard and crown of the pharaoh.

7. Hatshepsut’s coronation was an elaborate affair that was, apparently, attended by the gods themselves.

The coronation took place in the temple complex of Karnak over the course of several days. If we’re to believe Hatshepsut, her dead-but-deified father, Thutmose I, was the first to place the crown upon her head. The cow-headed goddess Hathor was also present, shouting a greeting and giving her a big hug. And the chief god, Amen-Re (also spelled Amun-Ra), “personally placed the double crown upon Hatshepsut’s head and invested her with the crook and flail of kingship, saying that he created her specifically to rule over his holy lands, to rebuild his temples and to perform ritual activity for him,” Cooney writes.

What better way for Hatshepsut to be seen as a legitimate monarch than by having received the blessings of the gods? She really wanted to hammer home the supposed events of her coronation day — she had images of the gods crowning her chiseled into the major house of worship of the time, Karnak, as well as her funerary temple at Deir el-Bahari.

SEE THE WONDROUS ARCHITECTURE of Hatshepsut’s funerary temple — and learn more about this surprisingly modern-looking structure.

8. Upon being crowned, Hatshepsut changed her birth name — yet another instance of gender ambiguity.

Hatshepsut added Khenemetenamen to the front of her name, “which, although unpronounceable for most of us,” Cooney writes, “essentially meant ‘Hatshepsut, United with Amen,’ communicating that her spirit had mingled with the very mind of the god Amen through a divine communion.”

Interestingly, she kept a feminine ending as part of the construction of that mouthful of a name. “There was no subterfuge about her femininity in her new royal names, but her womanly core was now linked with a masculine god through her kingship,” Cooney adds.

9. Hatshepsut’s royal names didn’t hide the fact that she was a woman. She was out to change the very perception of a king.

Egyptian kings liked to prove how macho they were, choosing names like Ka-ankht, Strong Bull. Hatshepsut’s Horus name was Useret-kau, Powerful of Ka Spirits, tying herself not to physical (and sexual) prowess, but to the mysterious might of the spirits of the dead.

Like her new birth name, Hatshepsut used the feminine -t ending. “She and her priests knew her limitations as a woman and seemed interested in flexibility rather than deceit,” Cooney explains. “She became king in name and title, but she knew that she could not transform into a king’s masculine body. She couldn’t impregnate a harem of women with any divine seed. There was no need for her royal names to point out those deficiencies or to lie about her true nature. Instead, she and her priests focused on how her femininity could coalesce with and complement masculine powers.”

Only kings wore these long false beards — though only Amun knows why!

10. Hatshepsut immediately upgraded her existing iconography once she became pharaoh.

All of the images of her as queen under Thutmose III were altered to show her as the senior king of a co-regency. “No longer would she be depicted as subordinate to Thutmose III,” Cooney writes. “Every sacred space in Egypt was changed, especially in the cultic centers of power, where an image translated into reality and to write or depict something was to make it come into existence.”

11. The color of Hatshepsut’s skin in her statuary demonstrated her progression from female to male.

Females in Ancient Egyptian art were shown with yellow skin, while males were red ochre. It’s thought that women were inside more often (weaving in the harem, one supposes) and didn’t get as tanned as the manly men out on military expeditions and the like. While Hatshepsut’s early statues stuck with the traditional yellow skin tone, later depictions, such as the ones showing her as Osiris, the god of rebirth at her funerary temple, are of an orange hue — a strangely androgynous colorization that must have baffled people at the time. By the end of her reign, Hatshepsut had adopted the red skin associated with males.

Statue after statue of Hatshepsut in a mummy pose like the god Osiris lines her funeral temple. The color has long since faded, but these carvings once had orange skin — in-between the yellow used for women and the red used for men.

12. In addition to skin color, Hatshepsut’s statues started taking on more and more male characteristics.

Early on, Hatshepsut’s genderbending positioned her as truly androgynous. On a lifesize statue from her funerary temple, she has a woman’s facial features, graceful shoulders and small, pert breasts — but she’s shirtless and wearing a king’s kilt. Even Hatshepsut must have felt that this cross-dressing image was a bit too shocking for the time. It was placed in the innermost chambers of her temple, away from the public, where only the most elite would ever see it. This drastic hybrid sexuality was never replicated.

Eventually, Hatshepsut’s statues had broader shoulders, and her breasts became the firm pecs of an idealized young man.

Because Hatshepsut presented herself as a male, Egyptologists can’t tell whether this is a statue of her or of her co-king, Thutmose III.

13. Hieroglyphic text went back and forth between referring to Hatshepsut as a female and as a male.

Sometimes she was “she;” sometimes she was “he.” On occasion, she was the Son of Ra, the sun god; more often she was referred to as the Daughter of Ra. Once in a while, she was called the “good god,” but most of the time — even accompanying a masculinized image of her — she was the “good goddess.”

14. Like many a pharaoh, Hatshepsut told a story of her divine birth.

The combo god Amun-Ra is said to have visited her mother in her bedchamber. “She awoke because of the fragrance of the god,” the text reads. I’m sure a bit more happened than this, but Hatshepsut chose to depict the moment as her mom and Amun-Ra sitting across from each other, hands touching, gazing sweetly into each other’s eyes.

This avant-garde woman rose to the highest political rank in a society over 3,000 years ago. So it shouldn’t surprise us to learn that after her death, her successor tried his very best to wipe all references to his aunt being king from the face of the planet. –Wally