Many, if not most, of the Scriptures were written by people falsely claiming to be the apostles or other leaders of the early Christian church, says biblical scholar Bart D. Ehrman. That means a lot of books of the Bible are actually forgeries.

The book of Mark, like the rest of the Gospels, was written anonymously. Why, then, do we believe they were products of the men that bear their names?

If your answer to any conundrum is, “It’s one of God’s miracles,” then this article is not for you. I seek the truth in facts — fully admitting that as we gain more and more knowledge, our previous beliefs can shift.

I don’t subscribe to the school of thought that blind faith can solve any mystery. I think about what is scientifically feasible, what archaeology and history research reveals, and base my judgments from there. Virgins do not give birth; men are not raised from the dead; and illiterate peasants do not write well-argued religious tracts.

“Most of the apostles were illiterate and could not in fact write.

They could not have left an authoritative writing if their souls depended on it.”

All that being said, this post is not about my beliefs. These are the findings of Bart D. Ehrman in his 2011 work, Forged: Writing in the Name of God — Why the Bible’s Authors Are Not Who We Think They Are.

“Most of the apostles were illiterate and could not in fact write,” Ehrman declares. “They could not have left an authoritative writing if their souls depended on it.”

Bart D. Ehrman was once an evangelical Christian who took everything in the Bible literally. Now he’s a biblical scholar whose works, like Forged, offer shocking truths about the supposed word of God.

So who wrote the New Testament, then? Most of the texts were composed by people with extensive schooling — that is, undoubtedly, members of the upper class elite.

Why would someone lie about writing these works? “Quite simply, it was to get a hearing for their views,” Ehrman explains. “If you were an unknown person, but had something really important to say and wanted people to hear you — not so they could praise you, but so they could learn the truth — one way to make that happen was to pretend you were someone else, a well-known author, a famous figure, an authority.”

Here are four shocking revelations about who actually wrote the New Testament (or, perhaps I should say who didn’t write it):

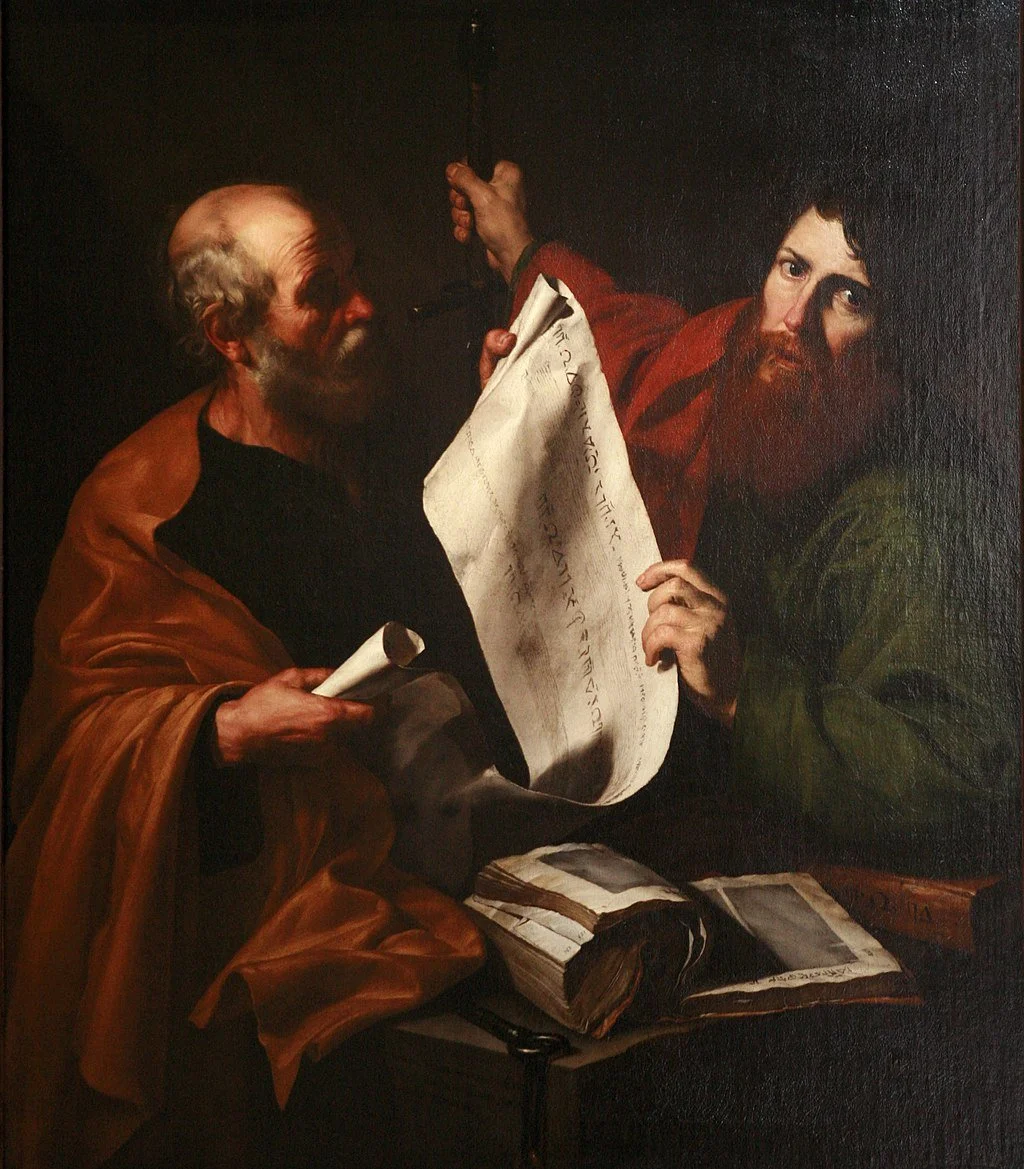

Peter and Paul had differing views of Christianity, but both were chosen as the “authors” of forged books in the Bible to lend authority to the writings.

1. Ancient writers forged writings to address infighting among early Christian groups.

Many people think of Christianity as always having been a well-defined, cohesive religion — as if the books of the New Testament were handed down from on high like the tablets of the 10 Commandments Moses received. But the truth is, the fledgling religion was a big old mess for hundreds of years.

“Christians in the early centuries of the church were in constant conflict and felt under attack from all sides,” Ehrman writes. “They were at odds with Jews, who considered their views to be an aberrant and upstart perversion of the ancestral traditions of Israel. They were at odds with pagan peoples and governments, who considered them a secretive and unauthorized religion that posed a danger to the state. And they were virulently at odds with each other, as different Christian teachers and groups argued that they and they alone had a corner on the truth and other Christian teachers and groups flat-out misunderstood the truths that Christ had proclaimed during his time on earth.”

So, numerous writers turned to forgery to give more weight to their arguments — and nowhere was that more prevalent than among varying factions of early Christians. Those works favored by church leaders centuries after Jesus were chosen to become the New Testament. Those that were deemed heretical (such as, say, the Gnostic Gospel of Judas), were not only left out but hunted down and destroyed in an effort to totally obliterate their teachings.

The book of Jude was written too late to have been authored by Jesus’ brother.

The New Testament book of Jude, for example, claims to be written by Jesus’ brother. But the author is talking about false teachers (which he strangely calls “waterless souls” and “fruitless trees, twice dead, uprooted”) who have infiltrated the religion and need to be rooted out — something that didn't happen until much later than Jude’s lifetime.

James was the head of the first Christian church, but couldn’t have written the book of the New Testament that bears his name.

And the book of James was supposedly penned by another of Jesus’ brothers, this one the head of the first Christian church, in Jerusalem. But not only was this book written after James’ death, the author is fluent in Greek and its rhetoric. Even if the timing worked out, the historical James, Ehrman says, was an Aramaic-speaking peasant who almost certainly never learned to read.

The New Testament itself declares that Peter was illiterate — so how the heck could he have written all those Bible books?

2. Peter was an illiterate fisherman who died years before 1 and 2 Peter were written.

Like the book of James, the book of 1 Peter was written by someone who was very well educated, spoke Greek and practiced rhetoric.

What do we know of Peter from the Bible? He was a fisherman from the town of Capernaum in Galilee. Archeological and historical records reveal that “Peter’s town was a backwoods Jewish village made up of hand-to-mouth laborers who did not have an education,” Ehrman writes. “Everyone spoke Aramic. Nothing suggests that anyone could speak Greek. Nothing suggests that anyone in town could write. As a lower-class fisherman, Peter would have started work as a young boy and never attended school.”

In fact, in Acts 4:13, Peter and his companion John are described as agrammatoi, a Greek word meaning “unlettered” — that is, illiterate.

There’s also the issue of timing. Tradition holds that Peter was martyred in Rome under Nero in 64 CE. But the author of 1 Peter alludes to Rome as “Babylon” — that is, the destroyer of Jerusalem and the Temple. The Romans didn’t destroy Jerusalem until 70 CE, six years after Peter died.

Peter, like all of the apostles, believed that Jesus’ Second Coming would take place during his lifetime.

In addition, the author of 2 Peter comes up with a defense as to why Jesus hasn’t returned as the Messiah. To God, “one day is as a thousand years and a thousand years are as one day.” So time is relative and just be patient.

But such an argument wouldn’t have been necessary for a disciple writing so soon after Jesus’ crucifixion. The Second Coming was predicted “within this generation” (Mark 13:30) and before the disciples “tasted death” (Mark 9:1). At the time Peter lived, Jesus could have still been right on schedule.

Paul actually did write some of the books of the New Testament — well, seven of the 13 attributed to him.

3. Good news! More than half of the letters attributed to Paul in the New Testament are authentic.

That means, of course, that six of the 13 are forgeries, though. Almost all biblical scholars agree that these seven letters were indeed written by the apostle Paul: Romans, 1 and 2 Corinthians, Galatians, Philippians, 1 Thessalonians and Philemon.

In the other books of the Bible attributed to Paul, there are words and phrases and writing styles not found in those that have been verified. And there are points made about Paul’s religious philosophy that just don’t jibe with what we know about his beliefs. For instance, the man was anti-marriage (even though he himself got hitched). In 1 Corinthians 7, Paul preaches that people should remain single. Why worry about procreation when the Rapture is going to happen any day?

But in the Pastorals (as 1 and 2 Timothy and Titus are referred to), “Paul” is insisting that church leaders be married. Side note: Why has this not become an argument to end the tradition of priests being celibate?

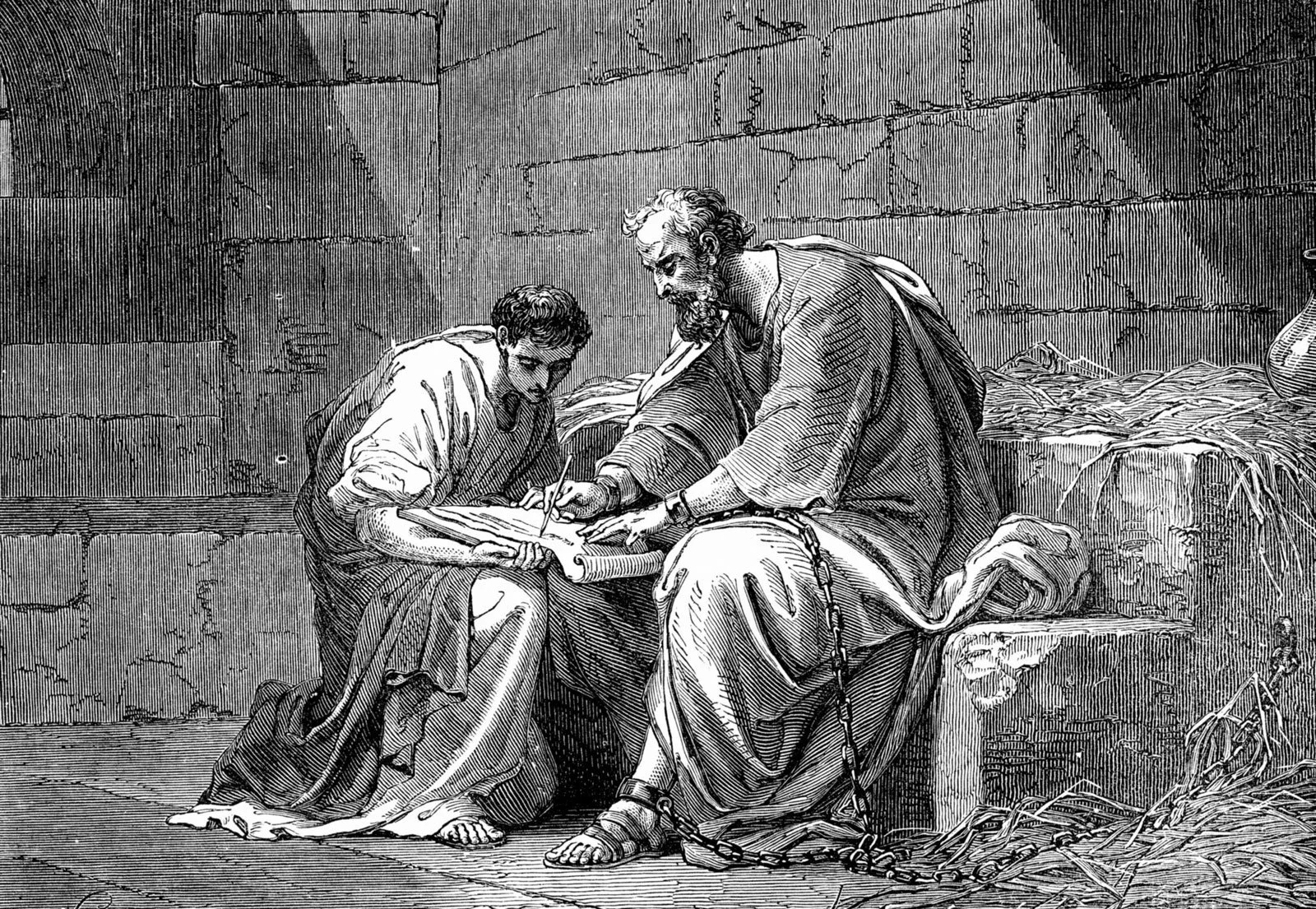

Scholars agree that at least a couple of the letters Paul wrote while under house arrest in Rome were actually penned by him.

Which brings us to another problem of timing: When Paul was alive, there weren’t any church leaders. His view was that every Christian was endowed with a supernatural gift (healing, say, or speaking in tongues) and all were equal: “In Christ there is neither slave nor free, neither male nor female,” he declares in Galatians 3:28.

Paul believed Jesus’ Second Coming would happen unexpectedly, “like a thief in the night” (1 Thessalonians 5:2), and he would be around to experience it. It wasn’t until a generation or more later, when people were still waiting, that some found it necessary to think more long term and offer up excuses.

“The author of 2 Thessalonians, claiming to be Paul, argues that the end is not, in fact, coming right away,” Ehrman explains. “There will be some kind of political or religious uprising and rebellion, and an Antichrist-like figure will appear who will take his seat in the Temple of Jerusalem and declare himself to be God.”

How could the same Paul declare in 1 Thessalonians that Jesus’ return would happen soon and suddenly, and then in 2 Thessalonians renege on that and state that a whole series of events had to take place first?

And in Ephesians, there’s also an issue with Paul’s biography. The writer includes himself as someone who, before meeting Jesus, was guilty of “doing the will of the flesh and senses.” But that doesn’t fit with the man who says, in undisputed letters, he had been “blameless” when it came to the “righteousness of the law” (Philippians 3:4-5).

An angel is said to have whispered the words of the Gospel to St. Matthew. But it turns out there’s evidence Matthew didn’t actually write the book of the Bible named for him.

4. One-third of the authors of the books of the New Testament — including the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John — were actually anonymous.

In fact, those texts remained anonymous for about a century. It wasn’t until around 180-185 CE that the Gospels were definitely named for the first time, by a church father and heresy hunter named Irenaeus.

And how did those authors get chosen? To lend the Gospels authority (and help assure they made the cut when choosing what would go into the New Testament), the writers were declared to be two disciples and two close associates of disciples.

Matthew, for instance, was a Jew, and tradition held that he had written a Gospel. So the first was assigned to him since it was deemed the most “Jewish.”

Church leaders ascribed authors of the Gospels about 100 years after they were written — anonymously, no less. There’s no evidence Mark actually wrote the book that bears his name, for example.

The second Gospel was determined to be by Mark on the scantest of evidence; he seems to have been chosen because of his connection to Peter.

When you hear the reasons the Gospels were assigned authors, like the book of Luke, you’ll realize how flimsy the evidence really is.

The author of Luke also wrote the book of Acts, where he proclaims to be a companion of Paul’s. “Because Acts stresses that Christianity succeeded principally among Gentiles, the author himself may have been a Gentile,” Ehrman writes. “Since there was thought to be a Gentile named Luke among Paul’s companions, he was assigned the Third Gospel.” So it goes.

John, the son of Zebedee, was assigned the Gospel with his name by process of elimination.

John, meanwhile, was supposed to be written by “the Beloved Disciple” it mentions (John 20: 20-24). In early tradition, the closest apostles to Jesus were Peter, James and John. Peter was named elsewhere in the book, and James had already been martyred. So that left John, the son Zebedee, as the author of the fourth Gospel.

Not the most convincing of evidence — but the Gospels couldn’t remain anonymous if they were going to become part of the Bible.

But wait — there’s more. In addition, Ehrman writes, “The anonymous book of Hebrews was assigned to Paul, even though numbers of early Christian scholars realized that Paul did not write it, as scholars today agree. And three short anonymous writings with some similarities to the Fourth Gospel were assigned to the same author, and so were called 1, 2 and 3 John. None of these books claims to be written by the authors to whom they were ultimately assigned.”

For biblical literalists, this evidence must be disturbing. Not only does it show that the New Testament contains lies, it makes us question the very beliefs at the core of what we know as Christianity.

That’s something to take up with God — or, perhaps, Ehrman. As he writes, “The use of deception to promote the truth may well be considered one of the most unsettling ironies of the early Christian traditions.” –Wally