From a haunted prison to a hotel with its own morgue, here are five terrifyingly popular U.S. destinations for ghost hunters, thrill seekers and paranormal tourists.

Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia, where solitary confinement originated

For those of us who like our vacations with a side of dread, the U.S. has you covered. Cursed plantations? Check. Derelict prisons? Yep. A floating hotel with a body count? You bet. These are the kinds of places where whispers echo in empty rooms, photos blur for no reason, and something unseen always seems to tug at your shirt.

Whether you’re a seasoned ghost hunter or just want to say you slept in the most haunted hotel in America, these are the must-visit spots that will make your heart race — and maybe stop.

1866 Crescent Hotel & Spa in Eureka Springs, Arkansas

Where the cancer cures were fake, but the bodies were real.

Originally built in 1886, the Crescent Hotel started as a luxury resort — and quickly spiraled into something much darker. After a short-lived first act, it was purchased in 1937 by Norman Baker, a con artist who turned the building into a sham cancer hospital. He operated without a license, performed grotesque procedures, and stored bodies in a basement morgue that still exists.

Back when the property was the Crescent College for Women

Guests and ghost hunters report sightings of Baker himself, nurses in old-timey uniforms, and figures wandering the halls at night. Want proof? You can join nightly ghost tours that take you to the most haunted corners of the property — including Baker’s old morgue.

1886 Crescent Hotel & Spa

75 Prospect Avenue

Eureka Springs, Akansas

Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Solitary confinement never really ends … if your ghost sticks around.

Once home to over 85,000 inmates — including Al Capone — this Gothic fortress pioneered solitary confinement, which sounded humane in theory and turned out to be more of a psychological torture chamber. The prison operated from 1829 to 1971 and is now a National Historic Landmark.

Its crumbling halls, rusted doors and echoing cellblocks give off a presence that’s hard to ignore. Visitors report disembodied voices, cell doors slamming on their own, and shadowy figures pacing inside locked cells. Cellblock 12 and the guard tower are said to be the most active — if you believe in that sort of thing. And even if you don’t, you’ll probably walk faster through them.

Sounds a bit like the derelict insane asylum attached to the Richardson Hotel in Buffalo, New York, which is also worth touring.

If you’re also going to Pittsburgh, be sure to creep yourself out at Trundle Manor.

Eastern State Penitentiary

2027 Fairmount Avenue

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

The Queen Mary in Long Beach, California

All aboard — for a cruise you’ll definitely want to disembark from.

This ocean liner hosted royalty, celebrities and WWII troops — and now ghosts. Docked permanently in Long Beach, the Queen Mary is considered one of the most haunted ships in the world.

Say hi to Jackie! She drowned in the pool but now giggles through the hallways.

Visitors regularly report paranormal activity, including screams, slamming doors and the ghost of a crewmember who was crushed by a watertight door in the engine room. Then there’s Jackie, the little girl who allegedly drowned in the pool and now giggles through the halls — creepy kid laughter being the ultimate test of your fight-or-flight response.

If you visit around Halloween (known to witches as Samhain), don’t miss the ship’s Dark Harbor event — a screamfest that brings its haunted legends to life.

The Queen Mary

1126 Queens Highway

Long Beach, California

St. Augustine Lighthouse in St. Augustine, Florida

Helping ships find the shore — and maybe helping spirits climb the stairs.

The current lighthouse was completed in 1874 — but the land has a longer, darker history. Tragedy struck during construction, when two young daughters of the superintendent drowned in the bay. Ever since, strange sightings have haunted the tower.

Visitors report hearing footsteps on the spiral stairs, catching glimpses of shadowy figures, and even being touched by something unseen. The Dark of the Moon tour takes you up the tower at night — just you, a flashlight … and your frazzled nerves.

St. Augustine Lighthouse & Maritime Museum

100 Red Cox Drive

St. Augustine, Florida

Myrtles Plantation in St. Francisville, Louisiana

Cursed ground, murder and ghosts with unfinished business. Southern hospitality not guaranteed.

The Myrtles has everything you could want in a haunted Southern plantation: hidden pasts, murder, mystery and a good chance of ghostly encounters. Built in 1796, the property is said to be cursed from the start, allegedly located on an indigenous burial ground. Several people died violently here, and stories of hauntings are as thick as the Spanish moss out front.

The enlarged section of this image is said to be the plantation’s famous ghost, a former slave named Chloe.

The most infamous ghost? Chloe — a formerly enslaved woman who was reportedly mutilated for eavesdropping and later hanged after poisoning members of the household. Her apparition has supposedly been caught in photos and is said to still roam the grounds.

Other spirits include William Winter, shot on the porch in 1871, and his young daughter, who died of yellow fever.

The Myrtles Plantation

7747 U.S. Highway 61

St. Francisville, Louisiana

An aerial view of Eastern State Penitentiary, which is no longer operational — just attracting visitors who appreciate the macabre.

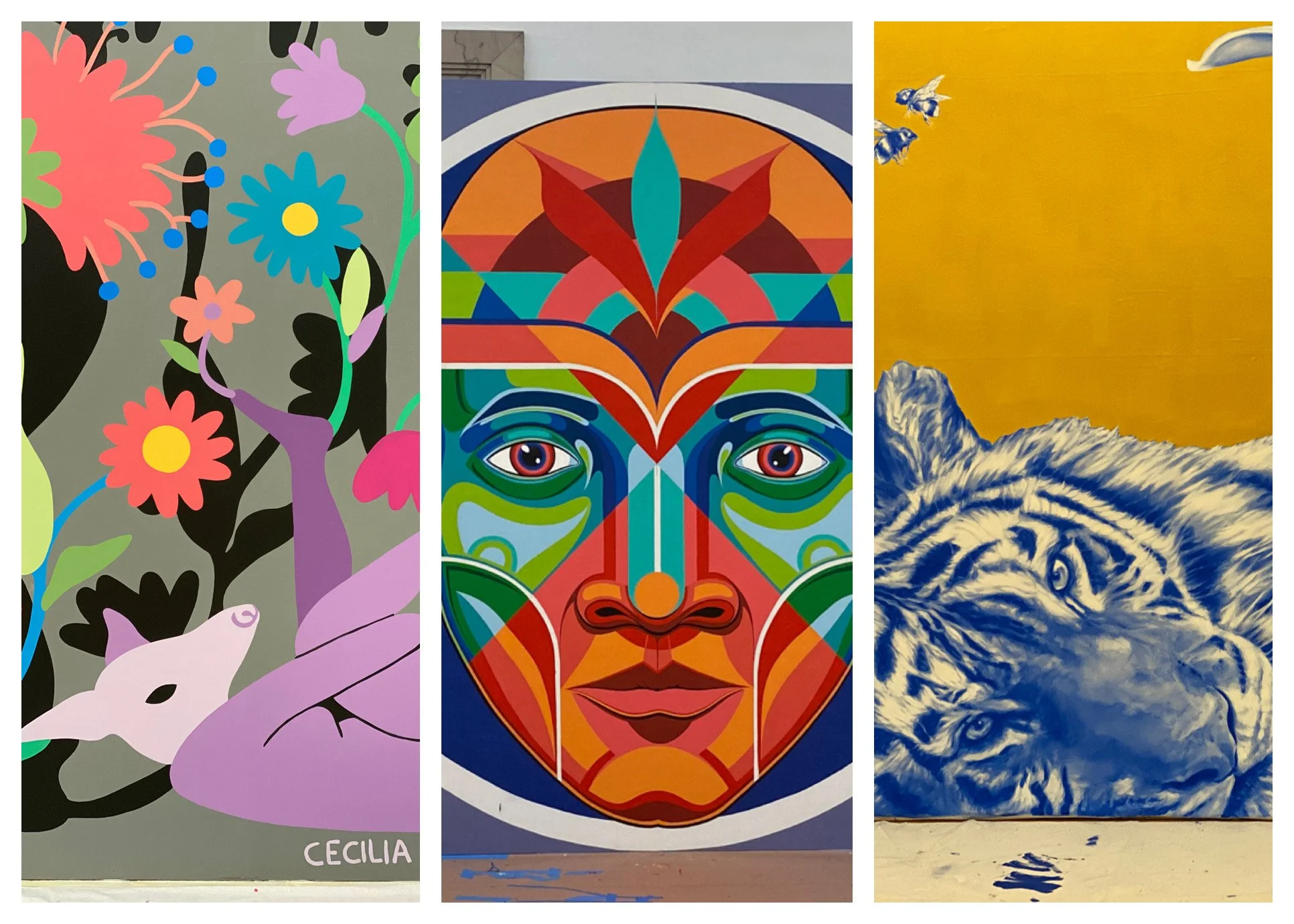

Haunted Hotspots

Some people go to the beach — others go looking for the ghosts of 19th century criminals. These haunted destinations deliver the perfect mix of history and horror, where the stories are real, the wallpaper is peeling, and the room you booked might come with a ghost you didn’t. –Armughan Zaigham