Say bonjour to a taste of France at the hottest bakery and breakfast spot in Oaxaca City, Mexico.

The open-air dining area of Boulenc has a bohemian vibe and an eye-catching pendant.

For Wally and me, the best places are often the ones shared among friends. This is how we came to make a pilgrimage to Boulenc, after one of my coworkers stayed at the attached hotel for a couple of days and raved about the food and atmosphere.

However, we didn’t realize how easy it is to pass by.

“Let’s talk about the real reason you go to Boulenc: the food and drink, which is beautifully presented and delicious.

They definitely serve up one of the best breakfasts in town. ”

Somehow we found ourselves getting lost in Oaxaca de Juárez, Mexico more often than we typically have in other cities. Centro, the “downtown” of this laidback town, has a dense and irregular network of streets that more than occasionally change names.

The unassuming façade of Boulenc is easy to pass by.

For this reason, we walked past the faded blue façade on Calle Porfirio Díaz a couple of times before realizing it was Boulenc. If the metal grille doors covered with flyers and a chalkboard that lead to the main dining patio happen to be closed, you’d never know you’ve reached one of the culinary hotspots of Oaxaca.

However, we were determined — and by our third day in the enchanting city, we arrived early and soon found ourselves having breakfast there. Boulenc is attached to and part of the panadería, or bakery, that brought the artisanal bread movement to Oaxaca nearly a decade ago.

Stop into the bakery next door for some delicious pastries and artisanal breads.

Juan Pablo: The Pope of Pastries

But let’s start at the beginning. The bakery’s mastermind and co-founder, Juan Pablo Hernández aka “Papa,” first took an interest in teaching himself how to bake bread, specifically sourdough, while working at a friend’s restaurant.

No one knows for certain how Papa acquired his nickname. However, Boulenc’s co-owner Bernardo Dávila has a theory. They’ve been friends since their teens, and Juan Pablo has had the moniker since he was very young. Bernardo thinks that it could be because Juan Pablo attended a Catholic school, and at the time, the name of the sitting pope was John Paul II aka Juan Pablo. In Spanish, the word for Pope is Papa — not to be mistaken with Papá, which means Dad.

Since his friend’s restaurant was only open for lunch and dinner, Juan Pablo asked if he could use the kitchen before it opened for the day to experiment and learn to make different types of non-traditional loaves, including the bread that started it all, sourdough.

Great food, great service and a charming boho chic vibe to boot

Starting From Scratch: The Rise Of Boulenc

In January 2014, Juan Pablo invited his good friends Bernardo and Daniel López to Oaxaca de Juárez to convince them that it was the right time to open a bakery. He had been selling his artisan bread as a side hustle. He had created a logo and landed on Boulenc, which comes from the word for bread maker in the Picard dialect of France.

“We came to Oaxaca right before the boom,” Bernardo recalls. “We knew that it had to be located in Centro, because that’s where all the restaurants and tourists are.”

The trio found a suitable location that was formally an art gallery space. It was within their budget — and became the first incarnation of Boulenc. It didn’t have much, Bernardo says, but it did have three capable co-owners who were up for the challenge.

Boulenc moved to a larger space and now has a boutique hotel attached (and some cool murals in the restaurant).

Their instincts had proven right. The bakery was quite popular and quickly found devotees. About two years later, one of their loyal customers asked if they might be interested in relocating to the colonial-era home across the street at Calle Porfirio Díaz 207.

“It’s a huge house,” Bernardo says. “When we went to check it out, there were just three people living there with three massive Neapolitan mastiff dogs. It was a little weird but it was also a good deal, so we said yes.”

So, in 2016 Boulenc relocated and went from being a cafeteria counter limited to seven customers to a full-blown restaurant that can accommodate up to 25 people.

Juan Pablo is known for his amazing pastries and breads.

A Passion for Baking and Local Ingredients

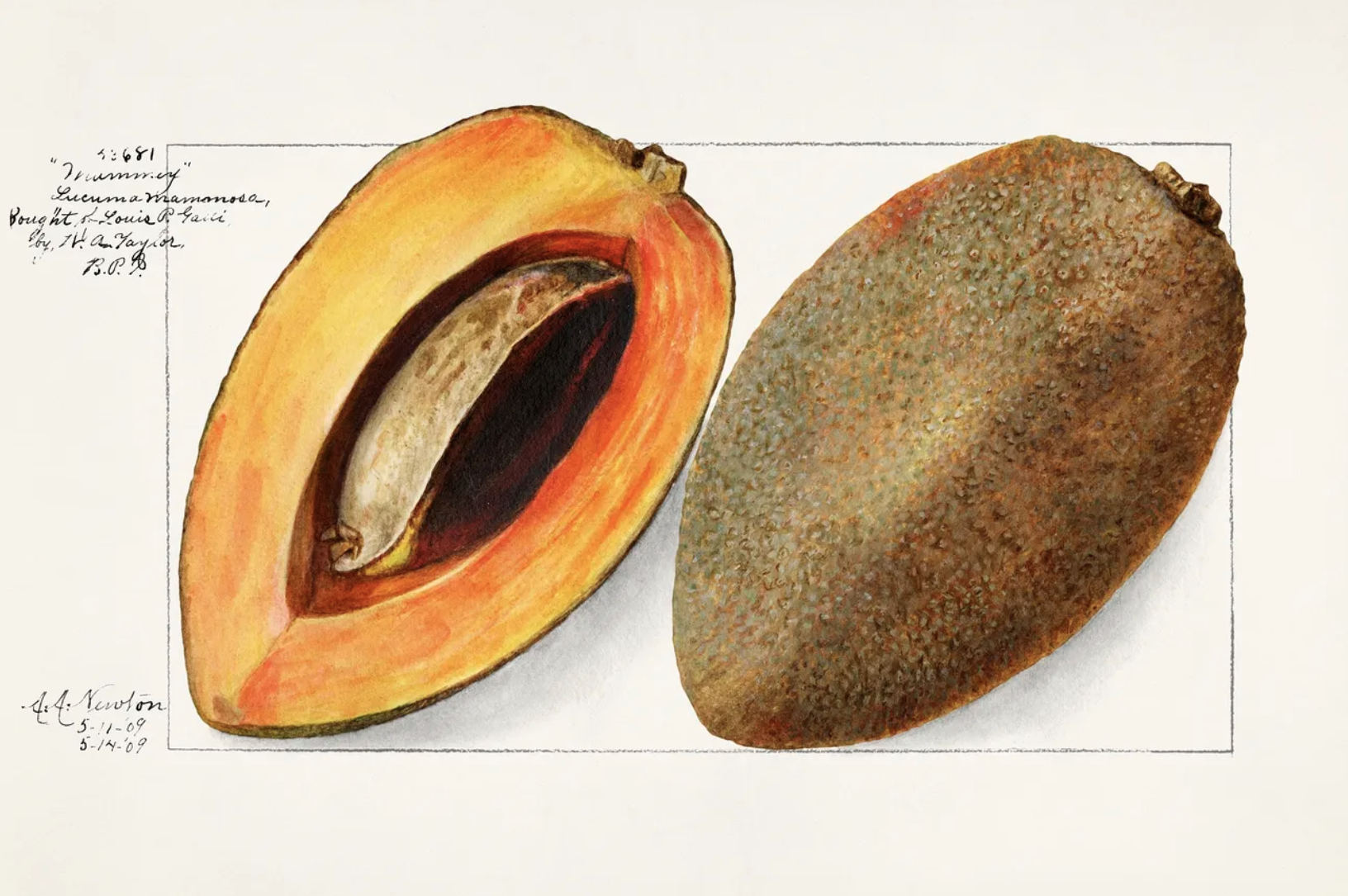

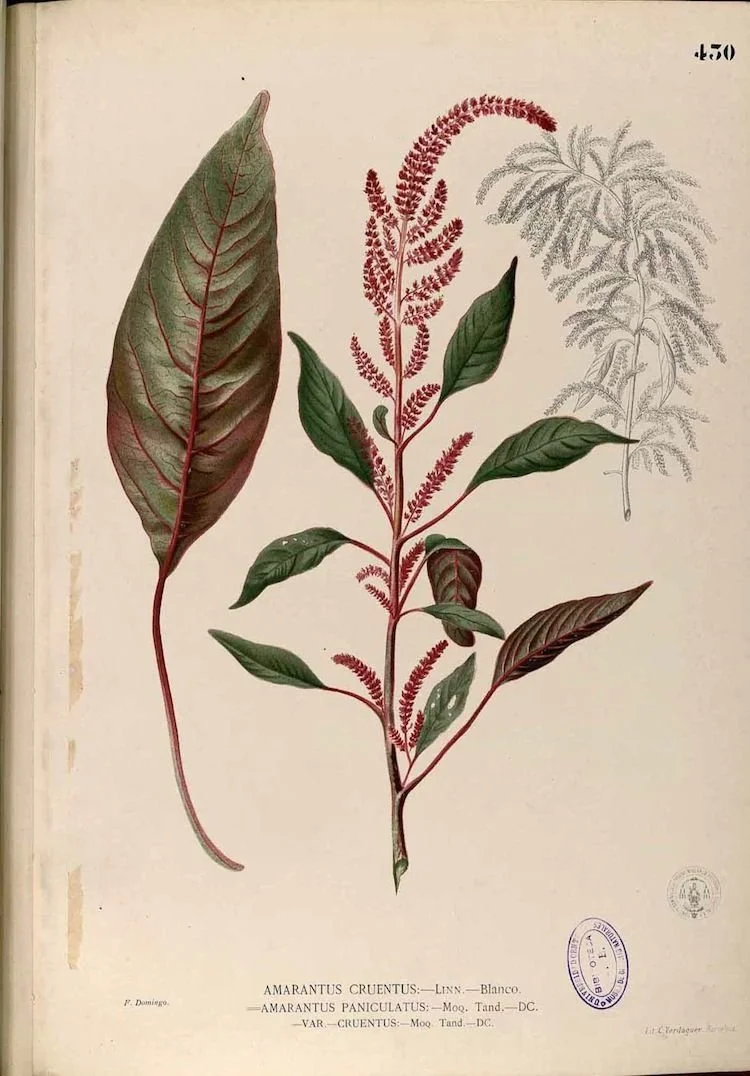

Juan Pablo is known for his passion for baking and his use of fresh, regional ingredients. He sources his flour from a nearby mill in Nochixtlan, and fruits, nuts and other ingredients from small local producers.

“I believe in using natural, healthy ingredients and making everything from scratch,” Juan Pablo told Plate magazine. “I’m very particular about the ingredients that I use, and I like to know where they come from.”

Boulenc has something for everyone, and serves breakfasts, salads, sandwiches, pizzas and a variety of beverages too long to list here. If you just want to grab something to go, there are European-style artisan breads, delectable pastries and coffee you can get at the bakery counter next door to the restaurant.

The bar at Boulenc has a cool wire sculpture created by the owners’ friends at Máscaras de Alambre.

A Fresh Start

Boulenc expanded the business by renovating and adding Boulenc Bed and Bread, a seven-room boutique hotel.

Paulina García, another co-owner of Boulenc, moved from Saltillo, Mexico and began making jams and preserves in the kitchen above the restaurant patio before experimenting with fermented foods. Eventually she and Daniel opened Suculenta, a provisions store next door to the café.

Both projects were completed and opened to the public in 2020.

Despite their success, the founders of Boulenc are constantly trying out new recipes and techniques.

“I’m always experimenting and trying new things,” Juan Pablo told the Oaxaca Times. “I’m constantly looking for ways to improve and refine our recipes, and to create new flavors that people will love.”

Most recently, the founders organized and attended a five-day cheesemaking workshop with David Asher from the Black Sheep School of Cheesemaking at a ranch outside of Oaxaca de Juárez. And knowing them, they’ll find a way to introduce some incredible homemade cheeses in the future.

Be sure to stop into Boulenc at least once during your time in Oaxaca — you won’t be disappointed!

Breakfast at Boulenc

Over the seven days that Wally and I stayed in Oaxaca, we came to Boulenc twice, and that’s high praise since they had tough competition from our hotel’s in-house coffeeshop, Muss Café.

Boulenc’s dining room proper is just beyond the doors I mentioned earlier. Inside is a tranquil, open-air courtyard with rustic wooden tables and chairs.

The walls of the interior courtyard reminded me of another excellent restaurant we dined at in Fez, Morocco called the Ruined Garden, which occupied part of a former dar, or traditional Moroccan home.

But let’s talk about the real reason you’re here: the food and drink, which is beautifully presented and delicious. They definitely serve up one of the best breakfasts in town.

During our first visit, I ordered a velvety cold brew that was so good I didn’t need to add milk. Wally had an iced latte, and since he ordered a second one, I know that he enjoyed his drink, too.

For breakfast, I got a stack of warm, fluffy pancakes made with rice, oat and almond flour served with bananas, blueberries, blackberries, strawberries and figs. This was accompanied by maple syrup served out of a copita, a small gourd cup, and housemade granola. Wally had the turkey ham and cheese croissant with a fried egg, chipotle mayonnaise and fresh tomato. Not traditional Mexican fare, but sometimes when you travel, you crave something continental.

There’s not a lot of seating, and Boulenc is a popular spot, so be sure to get there early.

A word of advice if you’re interested in having breakfast at Boulenc: Arrive early to avoid waiting in line. It’s a popular spot, and Wally and I made sure to arrive just before 8:30 a.m, when the restaurant opened. We were able to get right in. Breakfast is served until 1 p.m.

The restaurant runs like a well-oiled machine. The staff are friendly, knowledgeable and attentive, which made for a wonderful experience. And while we certainly didn’t feel rushed, there was already a line forming when we left at 9:15.

To one side of the restaurant is the bakery; on the other is Suculenta, an adorable provision shop.

After breakfast, we popped into Suculenta. You’ll find delicious jarred foods, cheeses, natural wines, organic fruits, vegetables and more.

We bought mustard with capers, mango and pineapple marmalade, a cocoa peanut butter and jabón de cacao (an exfoliating soap with cacao nibs from Mamá Pacha Chocolate).

Suculenta offers a selection of homemade condiments and other items, all charmingly packaged.

A variety of booze is on offer at the tienda, with a focus on natural wines.

If the store’s not open, you can also purchase a variety of their goods at the bakery counter.

The verdict: You might have to keep your eyes peeled to find it, but be sure to add this to your Oaxaca itinerary. And should you have to join the queue, know that it’s worth waiting for. –Duke

Boulenc

Calle Porfirio Díaz 207

Ruta Independencia

Centro

68000 Oaxaca de Juárez

México