André Breton lured Frida to be in a Surrealist show, but she found herself misled, miserable and mad as hell — until Mary Reynolds stepped in.

An exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago covers Frida’s turbulent time in Paris in 1939.

Paris was supposed to be her big moment. But when Frida Kahlo landed in the so-called City of Light in 1939, all she found was a hospital bed, missing paintings, and a bunch of filthy Surrealists who couldn’t get their act together.

Thanks to an interesting lecture by Alivé Piliado Santana, curatorial associate at the National Museum of Mexican Art (where we check out the Day of the Dead ofrendas every year) and Tamar Kharatishvili, research fellow in modern art at the Art Institute of Chicago, I’ve come away with a far deeper — and far juicier — understanding of this chapter of Frida’s life I didn’t previously know about.

“They are so damn ‘intellectual’ and rotten that I can’t stand them anymore .... I [would] rather sit on the floor in the market of Toluca and sell tortillas, than have anything to do with those ‘artistic’ bitches of Paris.”

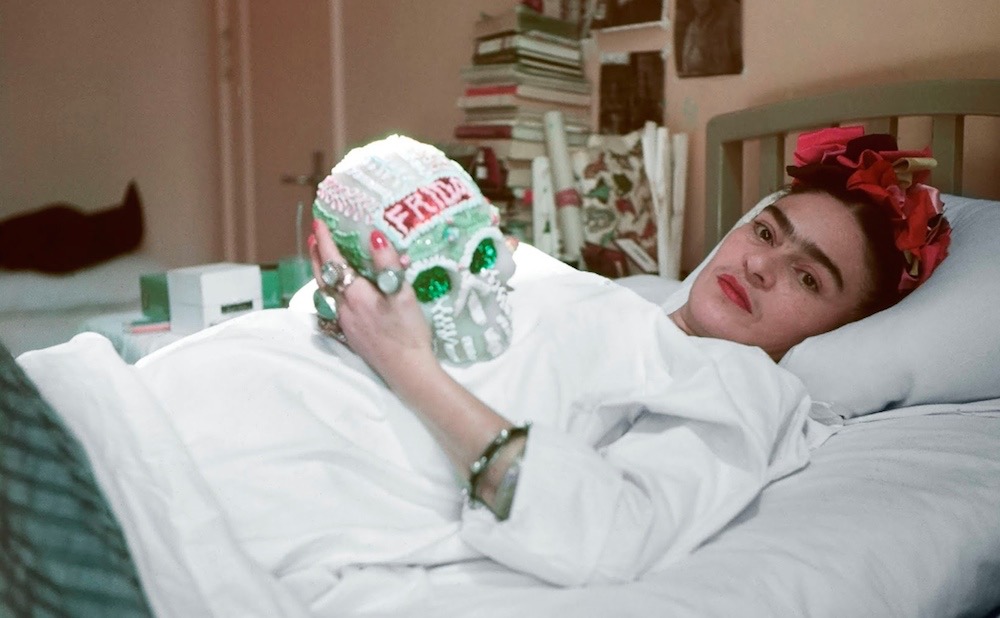

Wild child Frida in 1938

Here’s what I learned about the messy, maddening and frankly fascinating story of Frida’s Parisian misadventure, the forgotten women of Surrealism, and how a kindred spirit named Mary Reynolds helped turn Frida’s time in Paris into something meaningful.

André Breton, leader of the Surrealists and organizer of the 1939 Mexique exhibition — though “organizer” might be generous, considering Frida arrived to find no gallery, no show, and her paintings stuck in customs.

Frida’s Disastrous Arrival in Paris

It all began with an invitation that felt like a breakthrough. André Breton — the self-appointed “pope of Surrealism” — had reached across the Atlantic with a tantalizing offer. Frida Kahlo’s paintings, he declared, belonged on the world stage. He wanted her to come to Paris for a major exhibition he was organizing called Mexique.

Frida was excited for a chance to showcase her work in the artistic capital of the world, among the greats. It felt like a turning point — a chance to step out from her hubby Diego Rivera’s shadow and claim her place in the international art scene.

But somewhere along the way, wires got crossed. Frida thought Mexique would be a solo show.

It wasn’t.

Self-Portrait With Monkey, painted by Frida Kahlo, posing with one of her pets, in 1938 right before she left for Paris.

Frida prepared for the journey with cautious excitement. Before she left, photographer Nikolas Muray, with whom she was having a passionate affair, captured her in a series of now-iconic portraits: defiant, radiant and ready for her European closeup.

She could never have predicted how quickly things would unravel.

The troubles began before she even set foot in Paris. Her paintings, packed carefully for the voyage, were held up in customs. Instead of gliding smoothly into galleries, they sat in bureaucratic limbo, tangled in red tape. But there was still hope. Surely, Breton — the grand architect of the Surrealist movement — would have everything else ready.

He didn’t.

Frida arrived in Paris only to find chaos. There wasn’t even a gallery chosen for her show. No opening date on the calendar. No buzz of anticipation. Breton had made grand promises — but had done nothing to deliver on them.

A portrait of Frida taken by Nikolas Muray before she left for Paris

A Hospital Stay

On top of the professional humiliation, Frida’s health collapsed. She hadn’t arrived in perfect shape to begin with — just before leaving Mexico, she had undergone spinal surgery to try to ease the constant pain from an earlier accident. The long journey, the cold Paris winter, the stress of a botched exhibition, and the miserable conditions she found herself in were a brutal combination.

Part of her fury stemmed from Breton’s own visit to Mexico, where she and Diego had opened their home (now the Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo House-Studio Museum) to him and his wife — only to find that in Paris, Breton offered no such hospitality in return.

Almost as soon as she arrived, Frida developed a raging kidney infection, with a spiking fever that landed her in the hospital. She was exhausted, furious and rapidly losing faith in the promises that had brought her to Paris in the first place.

She pinned her illness squarely on the Surrealists’ squalor, convinced that their slovenly habits had done her in.

When she was discharged, still weak and recovering, she faced the grim reality of her accommodations: a dingy hotel, damp and depressing, in a city that felt far from the glamorous art capital she had imagined.

The final page of one of Frida’s letters to Muray. She didn’t exactly fall for Paris: “to hell with everything concerning Breton and all this lousy place,” she wrote, sick of the Surrealists and ready to go home.

She didn’t hold back. In a letter to Muray, she unloaded: “They are so damn ‘intellectual’ and rotten that I can’t stand them anymore .... I [would] rather sit on the floor in the market of Toluca and sell tortillas, than have anything to do with those ‘artistic’ bitches of Paris.” She thought the Surrealists were puffed up with self-importance yet utterly useless when it came to helping her. Only Marcel Duchamp, she noted acidly, “has his feet on the earth.” The rest, in her eyes, were pompous windbags throwing parties while her paintings languished in customs and her health deteriorated. And at the center of this mess, of course, was Breton himself, whose grand promises had led her straight into disaster.

What was meant to be her grand European debut had turned into a perfect storm of illness, neglect and bitter disappointment. She was stranded in Paris, her art trapped in customs, her patience wearing thin — and the Surrealists, led by Breton, had left her to flounder.

A photo booth pic of Mary Reynolds

Enter Mary Reynolds: An Unexpected Friendship

Just when Frida might have written off Paris entirely, in stepped Mary Reynolds — artist, bookmaker and all-around lifeline.

Unlike the aloof Surrealist men swanning around Paris, Reynolds opened her doors and, more importantly, her heart. Frida, still recovering from illness and spiraling frustration, moved out of her bleak hotel and into Reynolds’ home at 14 rue Hallé.

It wasn’t just a change of address — it was a change of atmosphere. Where Breton had offered chaos, Reynolds offered comfort. Her house in the southern part of Paris was a hub of creativity, conversation and, during the darkening shadow of World War II, quiet resistance.

Mary Reynolds with her partner, Marcel Duchamp

Mary Reynolds: The Unsung Hero of Surrealism

Reynolds deserves far more credit than she usually gets. A fiercely independent artist herself, Reynolds was a master of bookbinding — her works were collected by her partner, Marcel Duchamp (the guy who turned a urinal into modern art’s most notorious statement and further shocked audiences with Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2), along with other avant-garde heavyweights of the time.

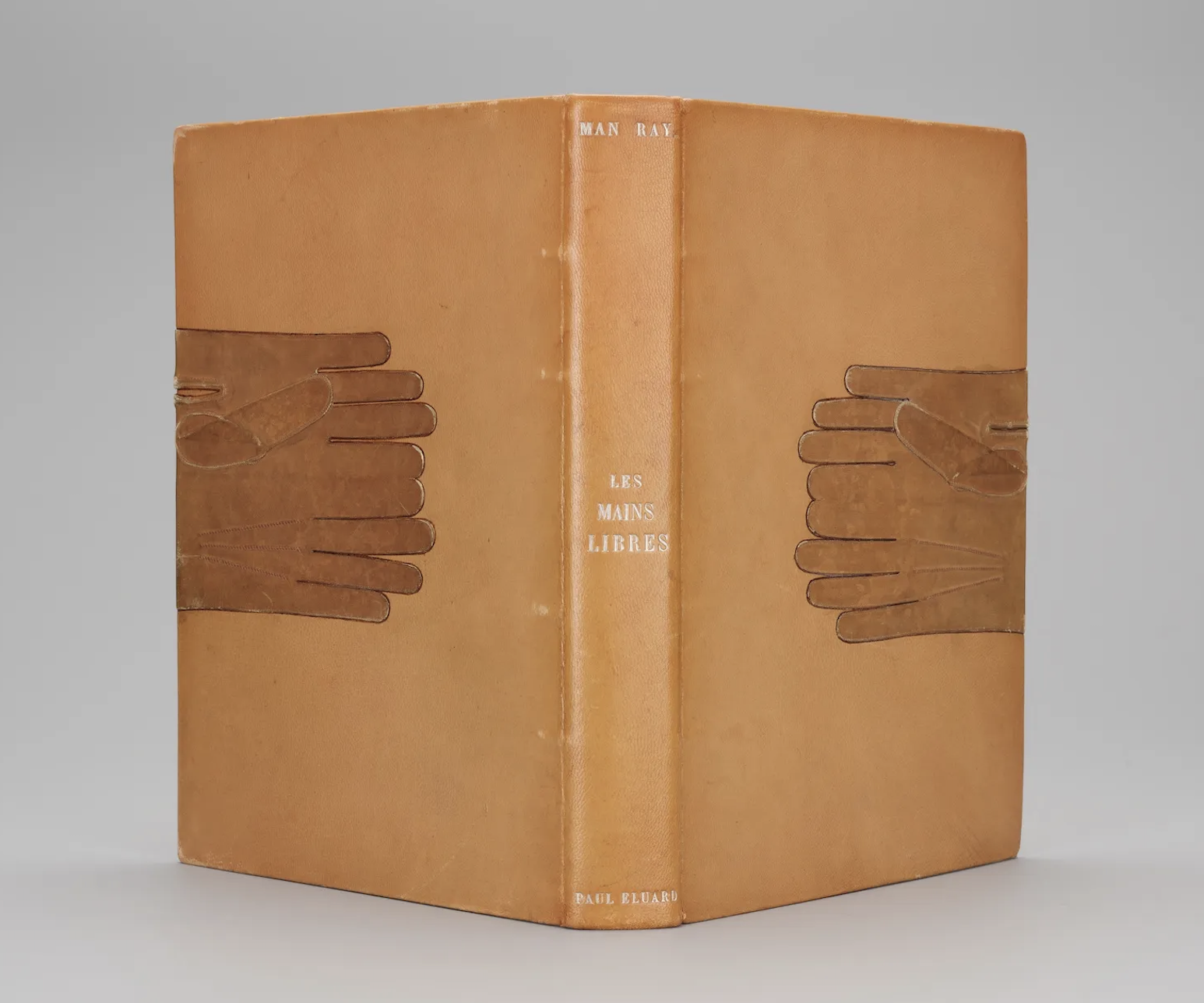

Reynolds took bookbinding to a whole new, surreal level: She used objects on the covers like kid gloves for Free Hands (Les Mains Libres), a thermometer in A Harsh Winter (Un Rude Hiver), and a teacup handle in Saint Glinglin — a nod to a scene where a character smashes plates with a golf club.

Reynolds was a genius when it came to bookbinding. Here’s the striking cover of Les mains libres (Free Hands) by Paul Éluard, with glove-like cutouts.

Her house was a living, breathing collage of Surrealist art and ideas. Duchamp, Alexander Calder and countless others had left their fingerprints — and actual works — all over her walls.

For Frida, Reynolds’ home was proof some Surrealists weren’t all talk and no action. Here was a woman making her own art, supporting her peers, and backing it all up with real-world bravery.

A delightful drawing of Mary Reynolds and her cats by Alexander Calder, the American modern sculptor best known for his mobiles

Kahlo and Reynolds: Finding Solidarity

The connection between Frida and Reynolds was electric. Both women were navigating the male-dominated art world on their own terms, refusing to be footnotes in movements led by men.

Their bond also feels emblematic of something bigger: a reminder that amid all the philosophical posturing of Surrealism, real solidarity happened where women supported each other, shared ideas, and, frankly, kept the whole thing afloat.

In Frida’s letters, you can almost feel the tone shift once she moves into Reynolds’ home. It’s not quite relief — her Parisian experience remained fraught — but there’s a spark of light. Reynolds gave Frida what Breton could not: genuine human connection in a city that had otherwise let her down. She stayed at Reynolds from February 22 to March 25, 1939.

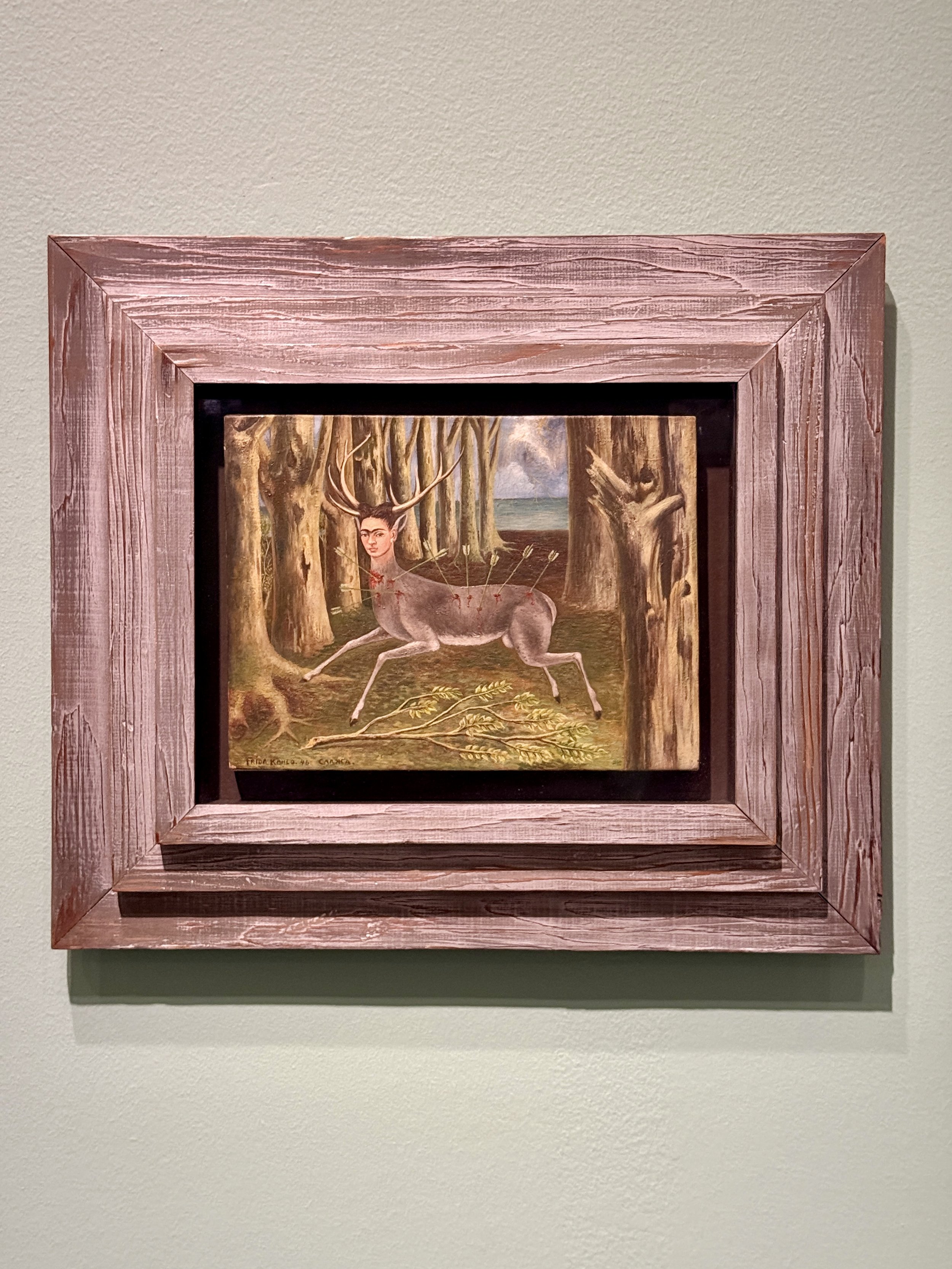

The Wounded Deer from 1946, painted after yet another failed surgery, this haunting self-portrait shows Frida as a deer riddled with arrows, calm-eyed in the face of relentless pain.

Frida and Surrealism: A Love-Hate Relationship

Here’s the irony: While the Surrealists were practically falling over themselves to claim Frida Kahlo as one of their own, Frida herself wanted nothing to do with the label.

Breton had famously declared her work “a ribbon around a bomb” — which, to be fair, is a great line. But Frida saw things differently. She didn’t consider herself a Surrealist at all. “I never painted dreams,” she once said. “I painted my own reality.”

Frida’s work, raw and visceral, didn’t need the Surrealist manifesto to explain it. Where the Surrealists dabbled in subconscious symbolism and found objects, Frida’s paintings were autobiographical to their core — her pain, her identity, her relationships all laid bare.

Self-Portrait With Cropped Hair from 1940. Freshly divorced, Frida depicts herself as wearing one of Diego’s suits, scissors in hand, her hair in clumps on the floor.

The Surrealists saw her as exotic, a muse from afar who fit their aesthetic fantasies. But Frida wasn’t interested in playing that role. She wasn’t a curiosity or a symbol — she was an artist, plain and simple. Her use of indigenous Mexican motifs, her explorations of physical and emotional suffering — these weren’t Surrealist exercises; they were her lived truth.

Still, despite her reluctance, Frida’s art undeniably aligned with many Surrealist themes. Dreams and reality intertwining, the use of found materials, the exploration of identity — it was all there, just coming from a much grittier, more personal place.

And she did, after all, agree to be a part of a Surrealist show in Paris. Which, by the way, finally came together. It ran at the Galerie Renou et Colle from March 10 to 25, 1939. Frida’s take on her fellow Mexican artists that Breton chose to showcase with her work? In one of her letters to Muray, she described them as “all of this junk.”

Photographer Nikolas Muray and Frida Kahlo had a passionate affair, and he was her confidante during her bad experience in Paris.

Nikolas Muray: The Confidant Behind the Letters

Long before Paris turned into a disaster, Frida had another anchor: Nikolas Muray. Photographer, Olympic fencer (yes, really) and one of her many lovers, Muray was one of the few people Frida trusted enough to confide in during her Paris ordeal.

Her letters to him are the sharpest, funniest and most brutally honest accounts we have of her time in France. She wrote to Muray not just to update him, but to release steam — to unload her frustrations about the Surrealists, the filth of the city, her failing health, and her utter disappointment in Breton’s empty promises.

The Tree of Hope, Remain Strong, painted in 1946 after spinal surgery. This double self-portrait splits her in two: One body lies wounded on a hospital gurney, while the other sits upright, dressed and defiant, clutching a back brace.

What Happened After: A Brief, Blazing Connection

For all the depth and warmth of their connection in Paris, Frida and Reynolds’ friendship seems to have been brief. After that whirlwind winter of 1939, there’s no evidence they kept up correspondence. Aside from one endearing letter where Reynolds talks about how empty the house felt without Frida, there aren’t any further exchanges that we know of.

Life pulled the two women in different directions. Frida returned to Mexico, her health still fragile but her art beginning to gain traction.

Reynolds, meanwhile, risked her life in the French Resistance. Her Paris home, once a haven for artists and thinkers, became a literal refuge for those fleeing Nazi persecution. She didn’t leave Paris until 1942, escaping across the Pyrenées on foot and finding a flight to New York. But she never stopped fighting for what mattered.

Their paths never formally crossed again, at least not that we can prove. But their legacies continued to intertwine, quietly and profoundly, through the art they made and the communities they helped build.

The Frame, an oil painting on tin with a vibrant folk art border, from 1938. Frida’s Paris show wasn’t a total disaster — the Louvre bought this piece for their colletion.

A Happy Ending to Frida’s Time in Paris

In spite of it all, Frida’s Paris disaster managed to end on a high note. Against the odds, her work finally made it onto the walls of a gallery — and not just any gallery. By the end of the show, the Louvre itself (yes, the Louvre) purchased one of her paintings, The Frame, making Frida the first 20th century Mexican artist in the museum’s holdings. Today (when not loaned out to travel), this emblematic self-portrait is part of the Musée National d’Art Moderne’s collection at the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

DID YOU KNOW? The Pompidou has a branch in Málaga, Spain?

Even more surprising, amid the wreckage of her Surrealist experience, Frida forged real friendships with a few kindred spirits. Man Ray, Duchamp and some others proved to be exceptions to the pompous crowd she had loathed. Some Surrealists were pas mal, after all. –Wally