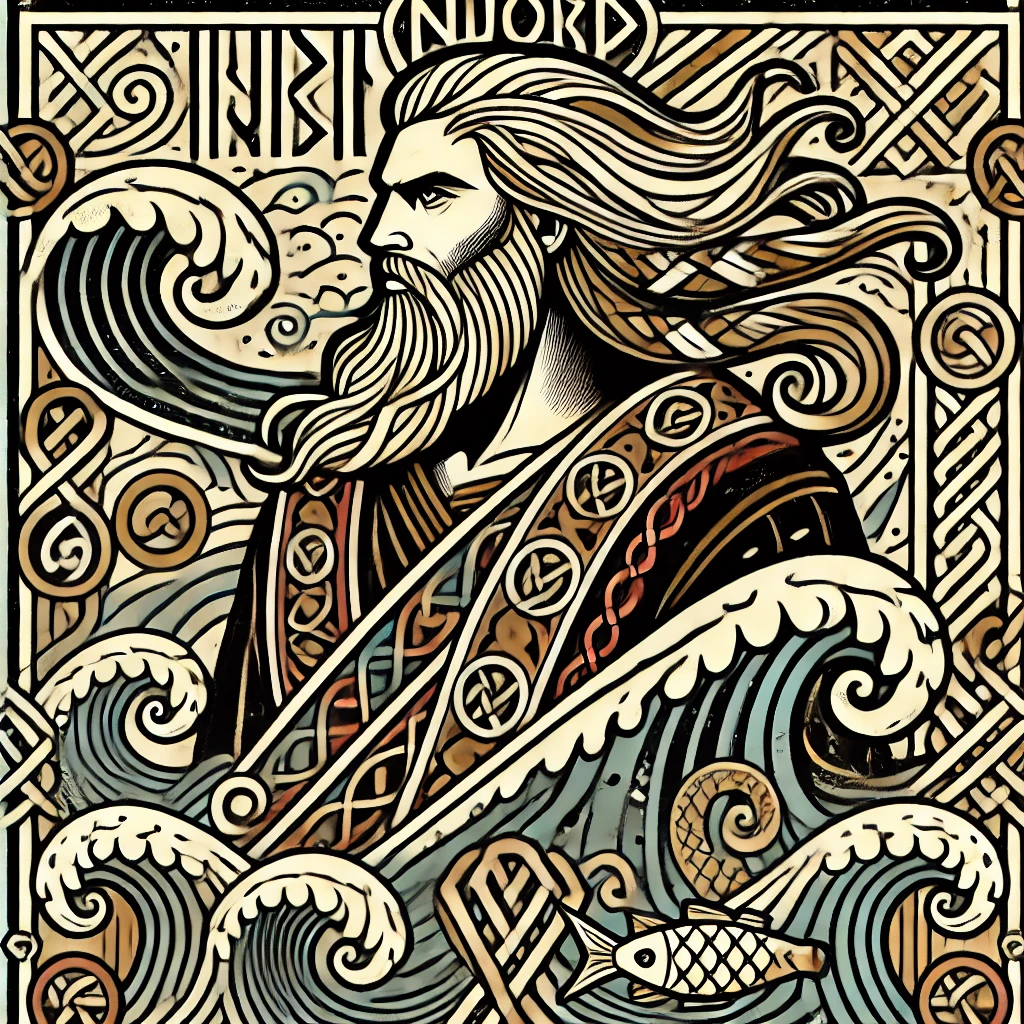

Long held up as a reason God hates gays, the Bible’s tale of Sodom and Gomorrah is soaked in fire, lust and cruelty — and its true meaning might not be what you expect.

The tale of Sodom and Gomorrah is so disturbing, I have to imagine it’s skipped over in Sunday school.

We read parts of the Bible as literature in my Honors English class (it was the ’80s, and it was in California). I couldn’t believe what I was reading: attempted gang rape of a couple of angels, a father offering his daughters to be raped instead, a city wiped out by fire from heaven, and a woman killed in a bizarre fashion for daring to look back on the destruction of her city. And all that’s before the insane incest episode.

If the men of your town want to gang rape a couple of angels, you could offer up your virgin daughters instead, like Lot did.

The Story of Sodom and Gomorrah Retold

The tragic tale of Sodom and Gomorrah begins with Abraham receiving three visitors near his tent (Genesis 18:1–2). One is presented as the Lord himself, the others as angelic messengers. (Follow the link if you’re curious about what God looks like, according to descriptions in the Bible.)

After announcing that Abraham’s barren wife Sarah will bear a son, the conversation shifts:

“Because the outcry against Sodom and Gomorrah is great and their sin is very grave, I will go down to see whether they have done altogether according to the outcry that has come to me” (Genesis 18:20–21).

It’s Noah’s Ark and the Flood all over again.

But Abraham does something no one expects: He bargains with God. “Will you indeed sweep away the righteous with the wicked?” he demands. Starting at 50 innocents, Abraham haggles down, until God finally agrees that if 10 righteous people can be found, the cities will be spared. Spoiler: It’s not looking good.

Two angels arrive at Sodom in the evening. Lot, Abraham’s nephew, sees them at the city gate and insists they stay at his house. Hospitality is a sacred duty in the ancient world — it involved food, shelter and protection for strangers.

RELATED: What did angels and monsters of the Bible actually look like?

But soon the men of the city surround Lot’s house and demand, “Bring them out to us, that we may know them” (Genesis 19:5). The Hebrew verb yadaʿ (“to know”) can mean simply “to be acquainted,” but this is unmistakably a sexual context: The crowd is demanding sexual access to the strangers — in plain terms, a gang rape.

Lot steps outside and does the unthinkable. “I beg you, my brothers, do not act so wickedly. Behold, I have two daughters who have not known any man; let me bring them out to you, and do to them as you please” (Genesis 19:7–8). In protecting his guests, Lot offers his own innocent daughters to the mob. It’s one of the Bible’s most horrifying moral reversals: The sacred code of hospitality is upheld by sacrificing family.

The crowd surges forward, but the angels intervene. They strike the men blind and warn Lot: Gather your family, because the city is about to be destroyed. Lot hesitates, so the angels drag him, his wife and his daughters outside the city and command them not to look back.

Then comes the fire and brimstone:

“The Lord rained on Sodom and Gomorrah sulfur and fire from the Lord out of heaven. And he overthrew those cities, and all the valley, and all the inhabitants of the cities, and what grew on the ground” (Genesis 19:24–25).

As they flee, Lot’s wife can’t help herself; she looks back — and she is instantly turned into a pillar of salt. The text doesn’t explain why. We’ll get into that later.

By morning, Abraham looks down and sees the aftermath: The cities are ash. The people have been slaughtered.

Was the sin of Sodom actually not homosexuality, but inhospitality? That’s what a prophet states in the Bible.

What Was the Sin of Sodom, Really?

Ask most people what Sodom and Gomorrah were destroyed for, and you’ll get one answer: homosexuality. The very word sodomy was coined from this story. For centuries, preachers and politicians alike have pointed to Genesis 19 as God’s final word on same-sex relations.

But here’s the problem: The text itself is more complicated — and so is the Bible’s own commentary on it. Let’s break down the main theories.

1. The homosexuality reading

On the surface, it seems straightforward. The men of Sodom demand Lot’s guests be brought out so they can “know” (rape) them (Genesis 19:5). For traditional interpreters, this sealed the case — Sodom was destroyed because of same-sex desire.

This reading has dominated Christian tradition for centuries. Theologians from Augustine to Aquinas hammered it home. English law codified it: “Sodomy” became shorthand for outlawed sexual acts, especially between men. Even today, when someone thunders about “the sin of Sodom,” they usually mean homosexuality.

2. Inhospitality and cruelty

But later prophets in the Bible revisit the story — and they say something else entirely. Ezekiel, writing in the 6th century BCE, names Sodom’s real guilt:

“This was the guilt of your sister Sodom: she and her daughters had pride, excess of food, and prosperous ease, but did not aid the poor and needy” (Ezekiel 16:49).

For Ezekiel, the problem isn’t sex. It’s arrogance, greed and cruelty to outsiders. Rabbinic tradition runs with this, imagining Sodom as a place where feeding the poor was a crime, and where cruelty to strangers was institutionalized. Michael Carden, author of Sodomy: A History of a Christian Biblical Myth, calls this the “counter-myth”: Sodom as the anti-charity city, not the gay city.

3. Sexual violence, not orientation

Another line of argument: The story isn’t about homosexuality at all, but about rape. The mob’s demand to “know” the strangers isn’t a request for consensual intimacy — it’s the threat of gang rape as a weapon of humiliation. In the ancient world, raping a man wasn’t about desire; it was about domination.

Scholars like Daniel M.G. Peterson (Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society, 2016) argue that Genesis 19 is about violent abuse of guests, not a blanket condemnation of same-sex relations. Todd Morschauser (Journal for the Study of the Old Testament, 2003) adds that the real violation here is against the sacred duty of hospitality — a core social law in the ancient Near East.

4. Angelic lust and “strange flesh”

And then there’s Jude 7, one of the New Testament’s strangest verses. It says Sodom and Gomorrah “indulged in sexual immorality and pursued strange flesh.” What’s “strange flesh”? Some scholars, like Richard Bauckham, argue it means the townsmen were lusting after non-human beings: the angels. This ties Sodom’s sin to another bizarre biblical episode, Genesis 6, where “sons of God” mated with human women. In this reading, Sodom’s crime is literally interspecies sex. Philo and Josephus, Jewish writers of the 1st century CE, leaned into the same interpretation.

So which is it?

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: The Bible itself doesn’t give a single answer. Genesis suggests violent sexual intent. Ezekiel condemns arrogance and neglect of the poor. Jude hints at lust for angels. And later interpreters layered centuries of theology on top.

The result? Sodom has been weaponized in debates over everything from sexual orientation to social justice to migration. Which makes the story less about what really happened in some desert city, and more about what every generation wants it to mean.

Did a Meteor Destroy Sodom and Gomorrah?

Modern scientists have even tried to explain this “fire from heaven” literally. In 2021, archaeologists at Tall el-Hammam in Jordan argued the site was destroyed by a cosmic airburst — a meteor exploding in the sky with the force of a nuclear bomb. They pointed to melted pottery, “shocked quartz” (minerals only formed under extreme heat), and destruction debris. The resemblance to Genesis 19 was uncanny: an entire city leveled in an instant.

But in 2025 the journal Scientific Reports retracted the paper, citing flaws in methodology and dating. Critics warned the evidence could just as easily be explained by conventional fire. Still, the idea isn’t so far-fetched. Events like Tunguska in 1908 prove that airbursts can flatten cities. If something like that happened near the Dead Sea, it’s easy to see how storytellers would remember it as divine fire raining from the sky.

Don’t look back. You might get turned into a pillar of salt like poor Lot’s unnamed wife.

Lot’s Wife: Punished, Petrified or Politicized?

When fire rains down on Sodom, Lot’s family flees into the hills. The angels warn them not to look back. But then comes the infamous moment:

“But Lot’s wife, behind him, looked back, and she became a pillar of salt” (Genesis 19:26).

No explanation. No name. Just a glance — and she’s erased.

This hauntingly brief verse has spawned centuries of speculation, interpretation and flat-out weirdness.

1. The moralistic reading

Most traditional commentators take it at face value: Lot’s wife was punished for disobedience. The church fathers doubled down on this, making her the ultimate warning against nostalgia for a sinful past. Augustine in City of God saw her as an allegory for those “who set their heart upon the things they left behind.” In Christian sermons she becomes a cautionary tale: Look back, and you’ll turn to salt, too.

But this interpretation is shaky. Genesis doesn’t say she disobeyed an explicit command not to look back (only that the family should “not look behind you” in Genesis 19:17). Was one backward glance really enough to justify obliteration?

2. The misogynist scapegoat theory

Feminist scholars point out that Lot escapes with impunity despite offering his daughters to a mob, yet his wife is destroyed for… turning her head. Phyllis Trible, in Texts of Terror, argues the story reflects a patriarchal worldview, where women’s bodies and choices are more heavily policed than men’s. Her erasure is less about sin than about the text’s need to silence her.

3. Geology and topography

Mount Sedom is a giant salt diapir (an underground dome of salt pushed up by tectonics) that produces natural pillars as it erodes. One pillar, still standing today, is even called “Lot’s Wife.”

Geologist Amos Frumkin has studied the region extensively, showing how the salt formations collapse and reform over time. In 2019, researchers mapped Malham Cave beneath it — the world’s longest salt cave, stretching more than six miles. This landscape generates what might be considered women of salt. The biblical story may have been a myth grafted onto a strange geological reality.

4. Josephus and the “I saw it myself” school

The Jewish historian Josephus (Antiquities 1.203) claimed he personally saw her salt statue near the Dead Sea: “I have seen it, and it remains at this day.” He wasn’t alone — later pilgrims also reported a “Lot’s Wife” pillar, treating her as a literal tourist attraction.

But note: Josephus is writing centuries after the supposed event. Was he describing an actual salt formation — one of many human-shaped columns along Mount Sedom — or simply playing into readers’ appetite for proof?

5. The metamorphosis theory

Others see the salt transformation not as punishment but as mythic metamorphosis, a trope familiar in Greek and Mesopotamian stories, where humans turn into stone, trees, stars or other objects. Scholar Tikva Frymer-Kensky points out that in the ancient world, such transformations were ways to explain uncanny natural features. Lot’s wife isn’t so much executed as fossilized into story — the Bible’s version of a myth explaining why a salt pillar looks like a woman.

Why the Story of Lot’s Wife Still Shocks Us

Lot’s wife lingers because she’s the most human character in the tale. Who wouldn’t look back as your entire world burns? Yet the text freezes her into silence, her memory crystallized in salt. Whether you read her as a moral lesson, patriarchal scapegoat or geological metaphor, she embodies the story’s strangest truth: Sometimes the Bible isn’t about justice at all, but about the terrifying cost of looking back.

What do you do when you think you’re the last survivors of an apocalypse? If you’re Lot’s daughters, the answer is as twisted as it gets: Get your father drunk, seduce him, and call it saving the human race.

Lot’s Daughters: Desperate Survival or Smear Campaign?

The story doesn’t end with fire or a wife turned to salt. It takes an even darker turn. In a cave outside of town, Lot’s daughters are some of the most intriguing women of the Bible. They believe they’re the last people alive and decide they must preserve humanity. Their shocking solution? Get their father so drunk that he won’t know what’s happening, then sleep with him on successive nights to conceive children. As disturbing as it sounds, the plan works:

“Thus both the daughters of Lot became pregnant by their father. The firstborn bore a son and called his name Moab… The younger also bore a son and called his name Ben-Ammi” (Genesis 19:36–38).

Why is this story here?

On the face of it, this is a grotesque act of survival — women convinced that humanity has been annihilated, preserving the family line at any cost. But as most scholars point out, this is less about family drama and more about national smear.

1. A political insult

These names could be construed as insults in Hebrew: Moab = “From Father,” Ben-Ammi = “Son of My Kin.” The text is inventing an incestuous origin story for Israel’s neighbors, the Moabites and Ammonites.

2. Echoes of trauma and survival

Some feminist and trauma theory interpreters argue the daughters’ actions should be read less as villainy and more as desperation. Trible calls them “victims turned perpetrators,” noting the way the text frames women as responsible for preserving lineage in a collapsing world. The fact that Lot is passed out drunk — silent, passive — makes him more of a tool than a father. In this reading, the daughters are both condemned and heroic, doing what’s necessary when the men fail.

3. Lot’s moral collapse

Readers often notice the contrast: Lot, once rescued by angels, is reduced to a drunken vessel of incest. He who offered his daughters to a mob now unknowingly fathers their children. It’s as if the text is saying: This man is no patriarch. His line doesn’t produce Israel but its despised neighbors instead.

4. Comparative myth: drunken fathers and cursed sons

Scholars like Frymer-Kensky point out that stories of drunkenness leading to shameful sex or exposure appear elsewhere in the Bible (think Noah and Ham in Genesis 9).

Even in a book filled with violence and betrayal, this story stands out. Incest, intoxication, national insult — it’s as messy as myth gets. And that’s the point. For Israel’s storytellers, the worst thing you could say about your enemies was that their ancestors were born of drunken incest in a cave. For modern readers, it’s a reminder that not all Bible stories are morality tales. Some are propaganda with a razor’s edge.

Have archeologists found evidence of an actual city of Sodom?

Did Sodom Exist? The Archaeology Wars

It’s one thing to read about sulfur raining from heaven. It’s another to try to find the ruins. For over a century, archaeologists and Bible-believers alike have gone hunting for the “cities of the plain.” The results? Charred ruins, wild theories and even a retracted scientific paper.

1. The southern Dead Sea theory

Back in the 1970s and ’80s, excavations at Bab edh-Dhrāʿ and Numeira, sites along the southeastern shore of the Dead Sea, revealed Bronze Age cities suddenly destroyed by fire. Ash and collapsed buildings looked like a smoking gun. Scholars like Paul Lapp and later Bryant Wood suggested these were Sodom and Gomorrah.

The problem? The dating doesn’t quite line up with when Genesis was written. These cities were destroyed around 2350 BCE, more than a thousand years before Israel’s storytellers put pen to papyrus. Still, for many, the fit was too good to ignore: real ruins for a fiery legend.

2. The Tall el-Hammam explosion

Fast forward to the 2000s. Archaeologist Steven Collins began excavating Tall el-Hammam, a massive mound in Jordan northeast of the Dead Sea. He argued this was the real Sodom — and in 2021, his team published a blockbuster paper in Scientific Reports.

The claim? Around 1650 BCE, Tall el-Hammam was obliterated by a cosmic airburst — basically, a meteor exploding in the sky with the force of a nuclear bomb. The story went viral: The Bible was right all along, and Sodom was nuked from the heavens.

3. The retraction bombshell

But science, unlike myth, has peer reviews. In 2025, the Scientific Reports editors retracted the paper after a wave of criticism. Other archaeologists pointed out flaws in dating, methodology and interpretation. Was there a destructive event? Probably. Was it a meteor? The evidence was inconclusive. And was it Sodom? That was wishful thinking.

In the end, the shovel hasn’t solved what the story means. Archaeology can uncover ash and ruin. But it can’t make the leap from disaster to divine fire.

Gomorrah barely gets its own story — it’s lumped in with Sodom, doubling the body count and amping up the horror.

Burning Questions About Sodom and Gomorrah

Taken as a whole, the story of Sodom and Gomorrah is one of the most unsettling in the Bible. Abraham bargains with God, only to watch the city go up in flames. A mob demands to rape angelic visitors, and Lot offers his virgin daughters instead. His wife is erased for a single glance. His daughters seduce him in a cave and give birth to Israel’s future enemies. And hovering over it all is the question: What, exactly, was the sin that brought fire from heaven?

For centuries, most Christians have answered: homosexuality. Yet the Bible itself offers multiple interpretations — violent inhospitality, arrogance and greed, even lust for angels.

What Sodom shows us is not divine clarity but interpretive chaos. The story has been a weapon, a warning, a myth to explain geology, a national insult and a theological Rorschach test. Every generation has found in it what it fears most: sex, strangers, arrogance, outsiders, women, enemies.

And maybe that’s the real controversy. Not whether sulfur actually fell from heaven, or whether a salt pillar still stands along the shores of the Dead Sea — but the way this story keeps being recycled to serve human agendas. The text itself smolders with a fire that never quite goes out. –Wally