Hopping through the history of the Easter Bunny, from pagan rituals to modern-day celebrations. Along the way, we’ll make some egg-citing discoveries about his birth as a fertility symbol and the origin of dyed eggs and Easter baskets.

Who knew the Easter Bunny evolved from the animal companion of a pagan goddess?

I once sponsored a child in India. His name was Papu Magi, and I regularly wrote him letters, sharing U.S. customs. When Easter rolled around, I explained how a giant human-sized bunny sneaks into our homes at night and leaves baskets filled with candy and colored eggs.

It wasn’t until I had written it out that I realized how bizarre some of our holiday traditions truly are. This got me thinking: How did we come up with the Easter Bunny?

“It makes you wonder if most Christians realize the holiday dedicated to the resurrection of their savior is actually named for a pagan goddess.”

Young women dance around a phallic maypole to increase their fertility — another pagan spring tradition.

A Pagan Origin: How the Easter Bunny and Dyed Eggs Became Symbols of Spring Celebrations

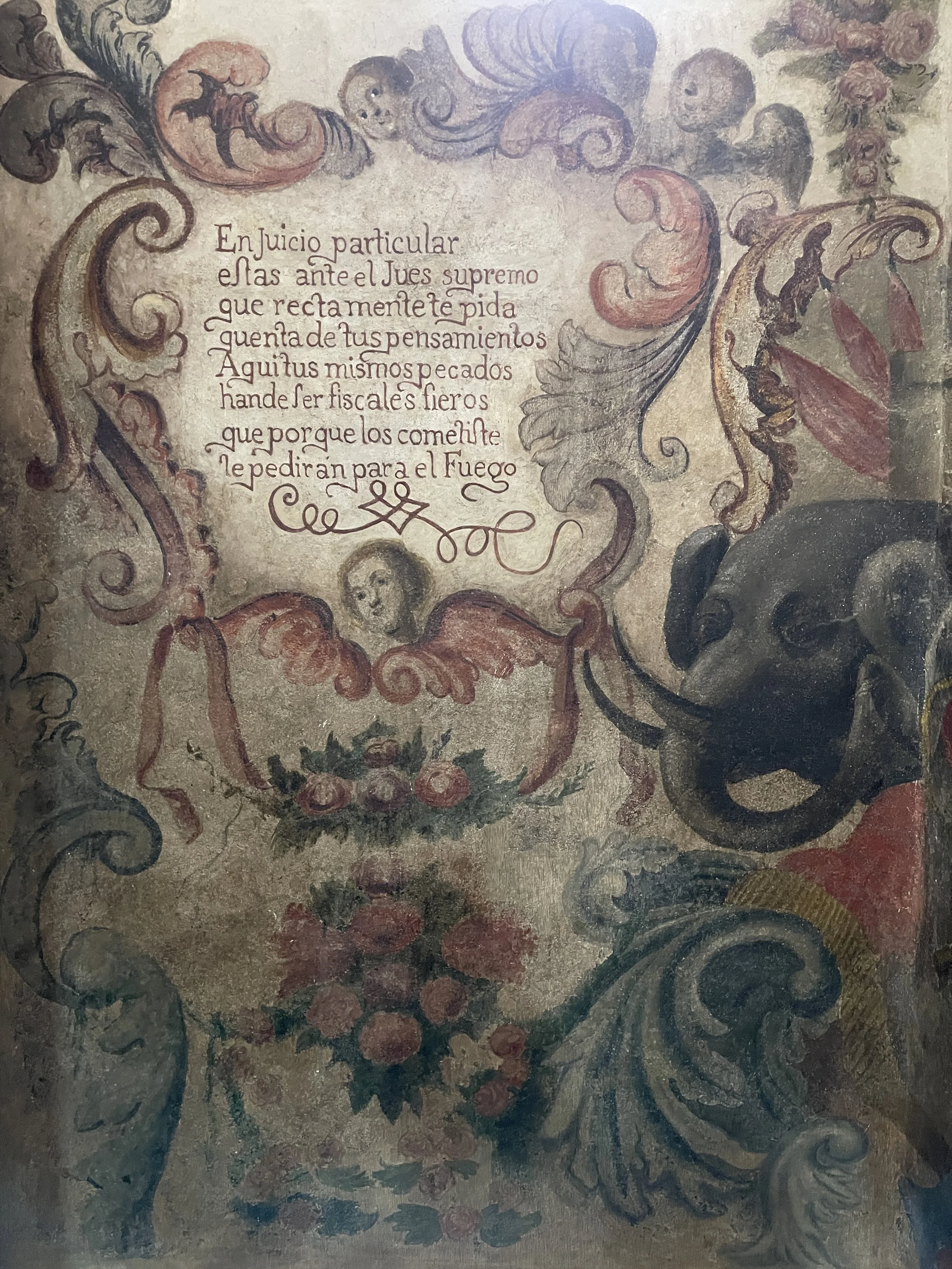

The origins of the Easter Bunny, as well as dyed eggs, can be traced back to ancient pagan rituals that celebrated the arrival of spring, including Ostara. Still practiced as a Wiccan holiday, Ostara is a celebration of the spring equinox. It’s named after the Germanic goddess Eostre, who some scholars deduce was associated with the dawn, fertility and new beginnings. (It makes you wonder if most Christians realize the holiday dedicated to the resurrection of their savior is actually named for a pagan deity).

Caveat: Hard evidence about Eostre is lacking, and the goddess remains shrouded in mystery. Much of what’s reported on her is conjecture.

Her first mention comes from a famous monk, the Venerable Bede, in 731 CE, who wrote that the Anglo-Saxons called April Eosturmonath, or Eostre Month, in honor a pagan goddess worshiped at that time.

Easter gets its name from Eostre, a pagan goddess of the spring.

These rites of spring were full of festive merrymaking, including dancing around maypoles, drinking mead and worshiping rabbits.

Yup, that’s right: Bunnies were a key figure in these celebrations. In pagan traditions, the rabbit was seen as a symbol of fertility and new life — no real surprise, given their well-deserved reputation for rapid reproduction.

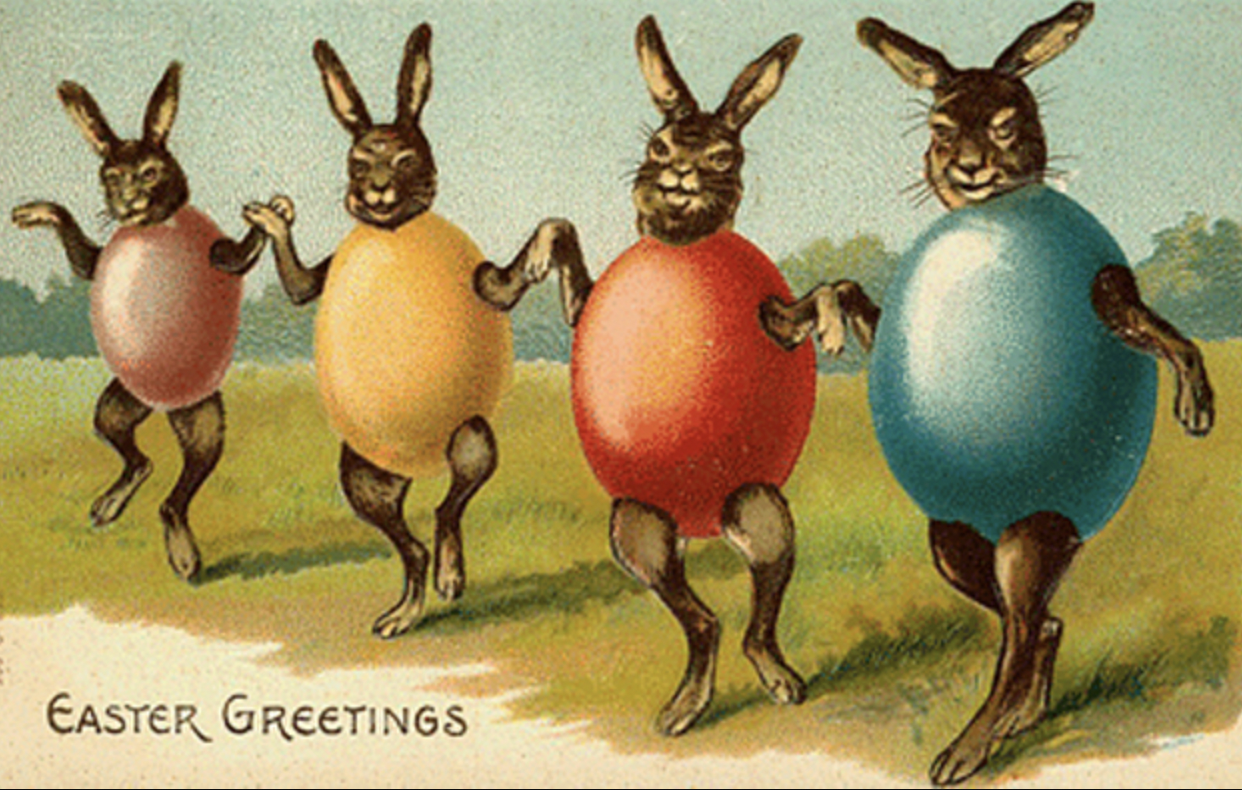

During these springtime celebrations, people would decorate eggs, believing them to have the power to bring new life and prosperity to those who ate them. Using natural dyes made from flowers and other plants, they created eggs in a variety of hues. And, as crazy as it might sound, rabbits were said to be responsible for laying colored eggs.

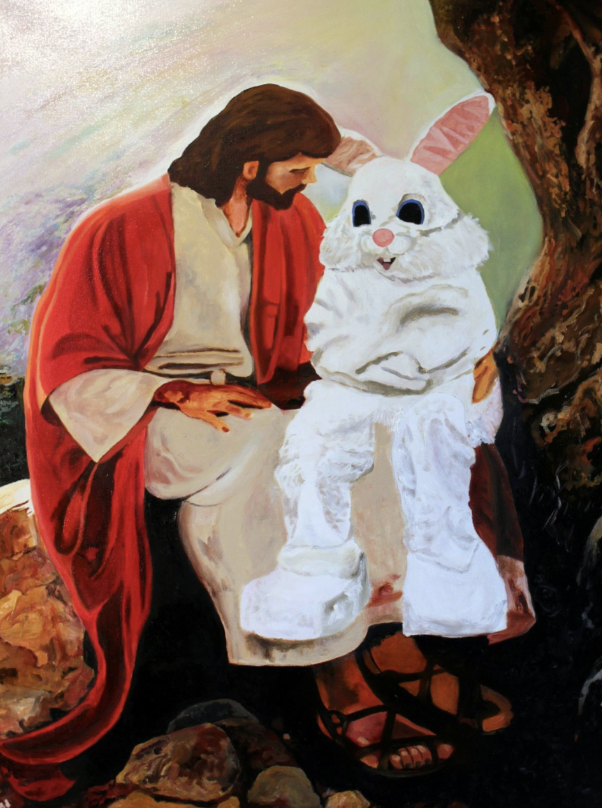

Do Jesus and the Easter Bunny belong in the same holiday?

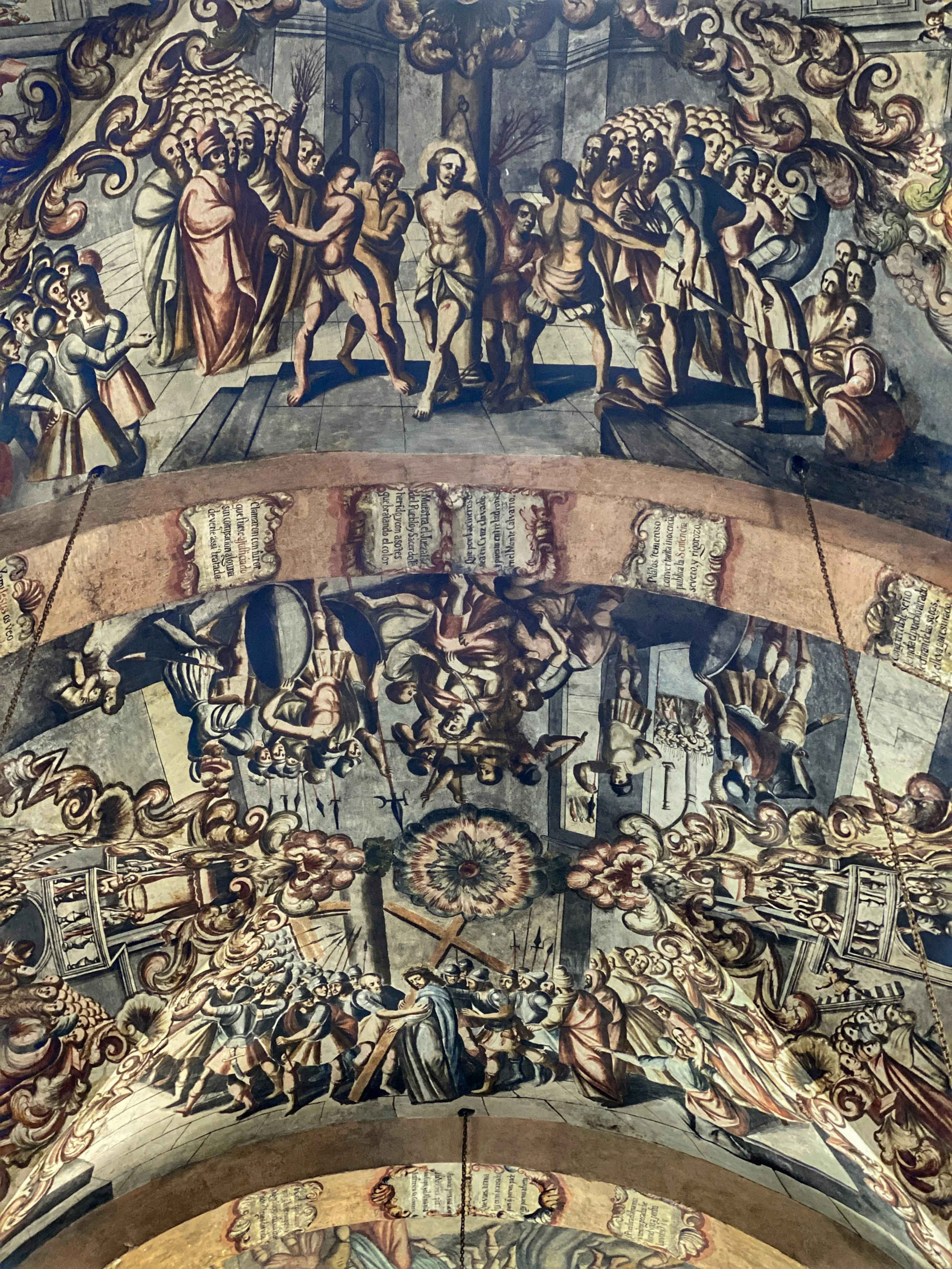

Hopping Into Easter: The Christian Origins of the Easter Bunny and Its Symbolism of Resurrection

The Easter Bunny may have its roots in pagan traditions, but it also had a significant place in Christian beliefs. The early Christians in Europe adopted many pagan customs and blended them with their own religious practices, which is how the Easter Bunny eventually found its way into the Christian tradition.

Much as with Christmas, some Christians bemoan the commercialization of the Easter holiday.

I’m not sure that many Christians today connect the commercial aspects of Easter with the religious ones (there’s a parallel to Santa and Christmas), but back in the day, early Christians associated the rabbit, and all of its spring rebirth symbolism, with Jesus’ resurrection.

It seems that Karen Swallow Prior, a professor of Christianity and culture at Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary, agrees. “There’s nothing wrong with dressing up in pastels, hiding eggs or consuming large amounts of chocolate,” she wrote in an op-ed in The Washington Post. “But if the fluffy white bunny takes precedence over the crucified and resurrected Lord, we’ve missed the point.”

Easter baskets came about from a pagan tradition to carry offerings to the goddess of spring.

The History of Easter Baskets: From Pagan Offerings to Sweet Treats

Easter baskets are a staple of the holiday, but how did they become a part of the Easter tradition? It turns out that the origin of the Easter basket is also closely tied to the pagan celebrations of spring.

In pagan traditions, baskets were used to carry offerings to the goddess of spring, including eggs, thought to increase fertility. Over time, the baskets became a symbol of the bounty of spring and were filled with all sorts of goodies, like flowers, fruit and vegetables.

Well, no wonder the Easter Bunny decided to switch to baskets!

As the Easter basket evolved, so did its contents. Today, they’re most often filled with candy (including a chocolate rabbit, which kids will disturbingly bite its ears off of) and other treats, filled by the Easter Bunny himself during a nocturnal visit — again, another connection to Santa Claus.

It’s hard to tell exactly when the Easter Bunny became adult-sized and anthropomorphic, but it seems like it might have happened around the 1950s.

Hare Today, Easter Bunny Tomorrow: Tracing the Evolution of the Beloved Easter Mascot

The Easter Bunny has been a beloved symbol of the holiday for centuries, but have you ever wondered how it evolved into the oversized, anthropomorphic creature we know today?

He didn’t start out that way. The hare, a smaller relative of the rabbit, was revered by ancient cultures for its speed, agility and ability to reproduce, and was often associated with the moon and the goddess of fertility. A study from 2020 draws a direct connection between Eostre and her association with the hare.

Bunnies and colored eggs have long been symbols of spring, representing new life.

As the hare became associated with pagan spring celebrations, it eventually evolved into the Easter Bunny we know today. This transformation was likely influenced by the German tradition of the Osterhase, a hare who laid eggs for children on Easter morning.

Jacob Grimm, one of the famous Brothers Grimm who collected oral folklore throughout Germany, said in 1835 that the Easter hare was associated with Eostre, or Ostara, as she would have been called in ancient German.

At some point, the Easter Bunny grew in size and children were told he visits their homes at night (much like Santa) to leave them candy-filled Easter baskets.

Vintage cards from the late 1800s to early 1900s show a lot of rabbits, but it seems like it wasn’t until the 1950s or so that the Easter Bunny became more and more human-like. Perhaps families or malls started having someone dress up like the Easter Bunny for photo opportunities. And despite the fact that the Easter Bunny became bipedal and reached 6 feet or so (not counting the ears), most kids believe he can’t actually talk.

Then again, it might have come down to marketing as a gimmick to help sell candy. “The Easter Bunny was created out of whole cloth by the confectionary industry,” claims David Emery, who writes for the fact-check site Snopes.

In another connection to Christmas, it has become a tradition to terrorize children by making them sit on the Easter Bunny’s lap for a photo.

Today, the Easter Bunny is a staple of the holiday, sometimes depicted wearing clothes — most often a vest and bowtie — and carrying baskets of eggs and treats.

To quote the M&M’s commercial, a fave of mine as a kid in the ’80s: “Thanks, Easter Bunny! Bawk! Bawk!” –Wally