Why would God pit brother against brother — and what exactly was the mark of Cain?

The tale of Cain and Abel reveals that it didn’t take long for sibling rivalry to manifest — and in a horrific manner. It’s a narrative of jealousy, fratricide and divine judgment. Yet, beneath the surface, this story is a theological Rorschach test, challenging assumptions about justice, fate and the very nature of God. Why did God favor Abel’s sacrifice over Cain’s? Was Cain always destined to be the villain? And does this story reveal more about human failure — or divine caprice? Scholars have wrestled with these questions for centuries, offering interpretations that range from moral instruction to thinly veiled critiques of the text itself.

“Believe it or not, in some Jewish traditions, Cain kills Abel by biting his neck.”

The Favoritism Dilemma: Why Abel?

The story’s most unsettling moment is also its crux: The two sons of Adam and Eve bring offerings to God, and one is inexplicably favored. Abel’s offering of “the firstborn of his flock” is accepted, while Cain’s “fruits of the soil” are rejected (Genesis 4:4-5). But why? The text remains maddeningly silent, leaving readers to puzzle over a seemingly arbitrary divine preference.

Gerhard von Rad argues in Genesis: A Commentary that the lack of rationale is deliberate, underscoring a recurring biblical theme — God’s choices often defy human logic, much like the seemingly unjust suffering of Job.

Some interpreters, however, shift the blame from divine whim to Cain’s own shortcomings. In The Beginning of Wisdom: Reading Genesis, Leon Kass suggests that Cain’s offering reflects his inner state: a heart not fully invested in his act of worship. The offering of fruit was less important than the spirit in which it was given, Kass argues. Cain, in this view, was the architect of his own downfall, his half-hearted devotion sealing his rejection.

Was Cain Set Up to Fail?

But was Cain ever given a real shot at divine favor? Some scholars argue that the narrative stacks the deck against him from the start. Robert Alter, in The Art of Biblical Narrative, notes that Cain’s name echoes the Hebrew word for “acquisition,” signaling his fixation on ownership and control — a precursor to his fatal envy. Alter sees this as foreshadowing, subtly positioning Cain as a tragic figure whose sin is less a spontaneous act and more an inevitable outcome of his character.

An Allegory of Agricultural vs. Pastoral Societies?

The Cain and Abel story also serves as a lens through which scholars view broader social dynamics in ancient Israel. Cain, the farmer, stands in tension with Abel, the shepherd — a reflection of the historical friction between settled agriculturalists and nomadic pastoralists.

John Van Seters, in Prologue to History, interprets the story as a mythologized conflict between two ways of life. The narrative reveals a deeper cultural tension, with God’s favoritism elevating the pastoral above the agrarian — it’s a dig at the encroachment of settled civilization on nomadic traditions.

The Serpent Seed Theory: Was Cain the Son of the Devil?

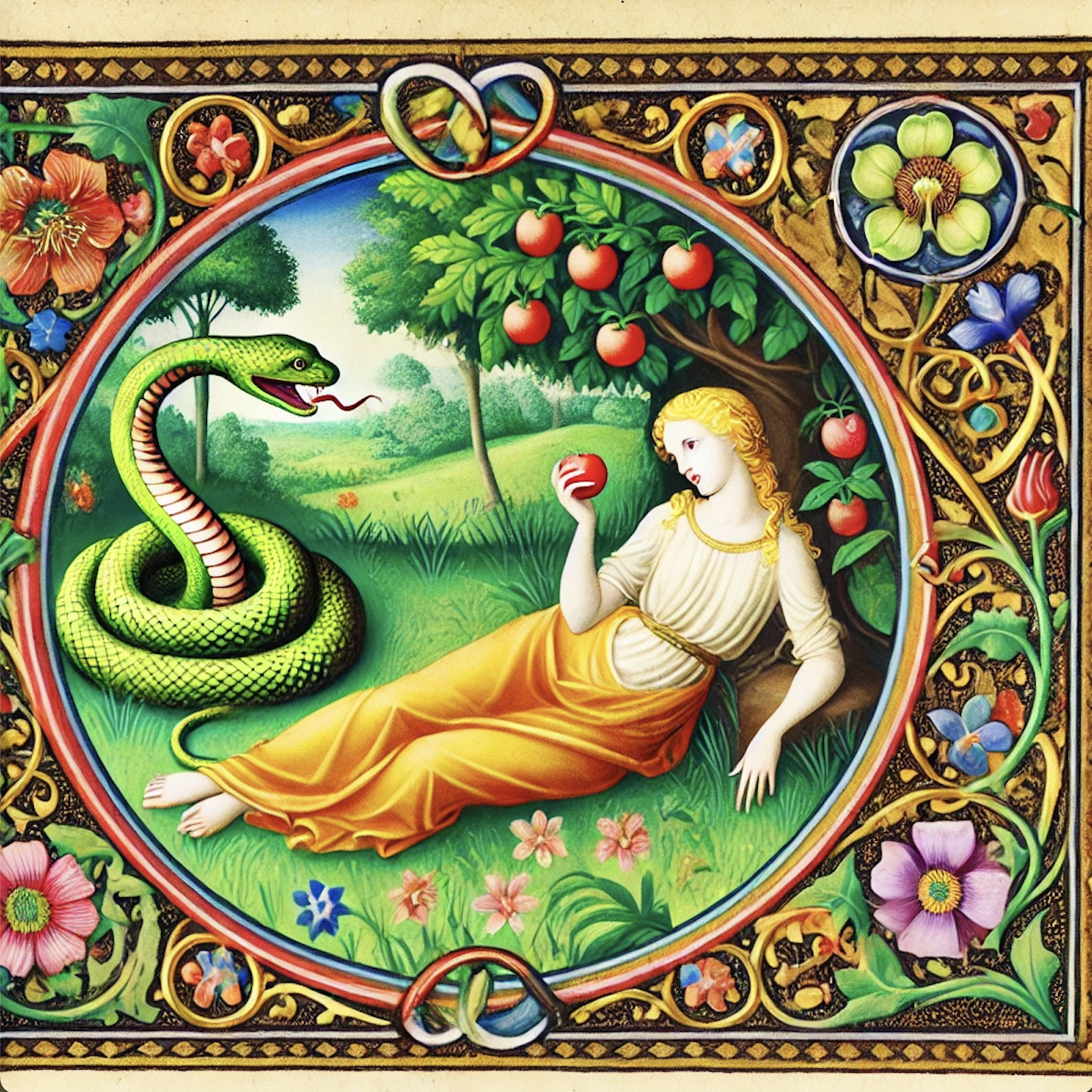

Hold onto your fig leaves — this one’s a doozy. What’s known as the serpent seed theory suggests Cain wasn’t Adam’s son at all but the love child of Eve and the serpent. That’s right, some folks believe the snake in Eden didn’t just hand Eve a snack but also fathered a line of human-demonic hybrids. Move over, Maury Povich — “You are not the father” takes on a whole new meaning.

Proponents of this theory latch onto Genesis 3:15, where God curses the serpent and speaks of its “seed” being at odds with Eve’s descendants. They argue this wasn’t just symbolic but a clue that Cain’s very DNA might have been less than human. And that infamous “mark of Cain”? These theorists think it might have been serpent-like traits: scales, reptilian skin or slit-like eyes.

Mainstream theology gives this theory the side-eye, dismissing it as pure hogwash. But, rooted in fringe theological circles and esoteric traditions, this interpretation casts a shadow over the entire Genesis account, reframing the first murder as a cosmic battle between divine and demonic lineages.

How Exactly Did Cain Kill Abel?

The Bible keeps it cryptic, as though nudging readers to ponder over the messy reality of human conflict. Genesis merely tells us that “Cain attacked his brother Abel and killed him” (Genesis 4:8). But the lack of details has sparked centuries of debate, each theory a reflection of the storyteller’s time and place.

The Stone

Many scholars, from ancient rabbis to modern theologians, argue Cain used a stone to strike his brother. This idea makes its way into commentary like The Legends of the Jews by Louis Ginzberg, where it’s suggested Cain saw the stone as both a weapon and a twisted reminder of the dust from which humanity was formed.

The Neck Bite

Believe it or not, some Jewish traditions add a far more primal touch. In these interpretations, like those found in The Talmud, Cain allegedly kills Abel by biting his neck. This brutal method underscores the story’s raw, animalistic nature — Cain attacks not with a weapon but with his own body, as if driven to murder by a more visceral rage.

A Sword or Tool

Medieval Christian artists sometimes depicted Cain wielding a crude sword or farming tool, suggesting he struck Abel with something close at hand, a symbol of Cain’s role as a tiller of the earth. This is the perspective you’ll see in certain illuminated manuscripts, where artists added their own medieval flavor to the story.

God’s Hand

An outlying theory, often linked to Gnostic or mystical interpretations, is that Cain’s anger somehow triggered a divine consequence. In these readings, Cain’s jealousy creates a rupture, allowing Abel to die without a physical act — almost as though God allows the anger itself to kill. This unusual perspective can be found in some early Christian texts, like those discussed in Gnostic Truth and Christian Heresy by Alastair Logan.

Each theory reflects the cultural lens of its time. Whether it’s a stone, a primal bite or divine intervention, the lack of specificity gives the story a mythic quality, inviting readers to consider not just the act but the consequences of unchecked anger.

The Mark of Cain: Curse or Protection?

Driven by jealousy and anger after God favors Abel’s offering over his, Cain lures his brother into the field and murders him in a fit of rage (Genesis 4:8).

After this horrifying act, Cain is marked by God — not as a curse, but as protection, ensuring that anyone who tries to harm him will face vengeance sevenfold (Genesis 4:15).

And what exactly was the mark? The nature of the mark of Cain has sparked wild speculation, ranging from a physical scar to a distinct feature like darkened skin, although these later interpretations often twisted the mark into a symbol of racial or social stigma. In its original context, however, most scholars agree that the mark was likely symbolic, representing divine mercy and protection rather than any visible disfigurement.

Ancient Jewish and Christian traditions offer a variety of theories. Some rabbinic texts suggest the mark was a supernatural sign, such as a glowing forehead or even the Hebrew letter tav etched onto his skin. Early Christian commentators like Augustine speculated that the mark was a form of trembling or perpetual wandering — an internal affliction more than an external brand.

But they all agree that the mark wasn’t a punishment. As Victor P. Hamilton points out in The Book of Genesis: Chapters 1-17, the mark is a striking blend of judgment and grace, revealing a God who, even in the act of condemning Cain, extends protection.

In this way, the mark of Cain complicates the straightforward idea of divine punishment. The first murderer in biblical history isn’t cast out entirely; instead, he’s given a form of protection that hints at God’s ongoing commitment to flawed humanity.

A Deeper Moral: Envy, Responsibility and Restorative Justice

At first glance, Cain and Abel reads like a straightforward morality tale about unchecked envy. God’s warning to Cain — “Sin is crouching at your door; it desires to have you, but you must master it” (Genesis 4:7) — is often interpreted as a timeless lesson in self-control.

But beneath this warning lies a story of complex responsibility. Walter Brueggemann, in Genesis: Interpretation: A Bible Commentary for Teaching and Preaching, suggests that Cain’s fate remains unresolved after the murder, leaving room for redemption. He sees a God who, even in judgment, allows space for healing and transformation. Of course, God’s favoritism is what caused the entire ruckus in the first place. –Wally