This impressive estate perched above the water was built for Isabelle Martin and shows the birth of Wright’s organic architecture.

Frank Lloyd Wright built Graycliff, a summer residence for the Martins, from 1926 to 1929 — just in time for the family to lose their great wealth.

Frank Lloyd Wright had to grow on me. Actually, more accurately, I had to experience his work firsthand to develop an appreciation for it. Because, to me at least, his exteriors can seem monolithic, the windows small, the horizontal planes somewhat uninteresting.

But when you enter one of his homes, it’s like you’ve entered a magical realm — the unassuming wardrobe that opens into the fantastical realm of Narnia, if you will. Wright transports you to another world, a cozy space where nature is invited in, often in surprising ways. You develop a great respect for the thought and vision that went into each of his homes. The environment connects to the site with a palette inspired by, and often using, materials sourced from the immediate area.

“When the Martins complained about the additions, Wright replied, “You don’t need them — but the house does.””

Our docent, Gail, was extremely knowledgeable about Graycliff and its colorful history.

The Martin Family and the History of Graycliff

Graycliff was the lakeside haven and summer home of Isabelle and Darwin Martin. Darwin was a wealthy executive at the Larkin Soap Company and first met Wright at his Oak Park studio in 1902 to discuss the commission of a Larkin Administration Building. He later commissioned Wright to design and build the home that would become Graycliff. The estate is perched atop a 50-foot bluff overlooking Lake Erie in the town of Derby, New York, about 20 miles south of Buffalo. In the distance, you can see the Point Abino Lighthouse and the Welland Canal in Canada.

The Larkin Soap Company was a massive mail-order business, and Darwin one of the highest paid executives at the time (worth the equivalent of $40 million nowadays). This accounts for his ability to build not only Graycliff but the family home in Buffalo (known as the Martin House) with Wright — an architect notorious for not letting a budget get in the way of his vision.

But all of that changed when the stock market crashed in 1929, ushering in the Great Depression. Darwin had heavily invested in a number of his son’s business ventures, including 800 West Ferry, a luxury apartment high-rise in Buffalo. Due to these underperforming investments, the Martins’ fortunes eroded.

Darwin sustained a series of mild strokes and a more serious episode on December 17, 1935, resulting in his death.

It was reported that upon hearing of Darwin’s death, Wright stated that he had lost his best friend and most influential patron. Over the years, Darwin loaned Wright approximately $70,000. None of it was ever repaid.

Isabelle continued to spend summers at Graycliff until about 1941. When she could no longer afford to keep the main house open, she moved into the apartment above the garage in the Foster House, before passing away on February 22, 1945 at the age of 75.

Wright probably never imagined a modern sculpture sitting on the lawn at Graycliff — but we like to think he’d approve.

Wright’s Vision for Graycliff

Construction of the estate began in 1926 and was a gift from Darwin to Isabelle, upon his retirement from the Larkin Soap Company. The Martins were able to spend their first summer there in 1929, though the grounds weren’t completed until 1931.

The complex comprises the main house, a sunken boiler house (called the Heat Hut) and the Foster House, originally conceived as the chauffeur’s quarters, so named because it was used as the summer residence of Isabelle’s daughter, Dorothy Martin Foster, her son-in-law, James, and their two children.

Graycliff is named for the natural feature that forms the overlook it’s perched upon, and despite sounding a bit dour, the house is actually bright and airy. Not only did Wright want to provide views of Lake Erie, he had another reason to fill the house with natural light: Isabelle suffered from scleritis, a condition that causes chronic eye pain and light sensitivity. According to correspondence sent from the Martins to Wright, Isabelle needed a place that was flooded with “light and sunshine” — the opposite of their city home, which was dark and difficult for her to navigate.

The view of the lake through the home was destroyed for a while when the Piarist priests put their chapel here.

The Piarist Priests: The Other Owners of Graycliff

In the 1950s, the Martin descendants sold the property to the Piarist Fathers, a Roman Catholic teaching order from Hungary. The Piarist edict being education for every child, they formed Calasanctius High School in Buffalo and needed residences for 24 priests and a boarding home for 48 underprivileged students.

When the priests purchased the property, they also needed a chapel to accommodate the large Hungarian community in the area. So they tore out a wall to create a new entrance and replaced the windows of the cantilevered porch with colored glass — thereby cutting off the view of the lake through the house and destroying Wright’s main vision for Graycliff.

The story goes that when Wright was 91, he visited Graycliff, unannounced, with some protégés.

The architect pulled up, and the head priest, recognizing the fancy car, ran out to greet him. Taking one look at the alterations, the first thing Wright says is, “Who did this? This is not my work.”

“We needed a chapel,” the priest stammered.

“Well, I can design you one,” Wright said.

Ignoring the priest, he turned to his colleagues and said, “Come on. I’ll show you the house.” And in they walked, uninvited.

Wright never got to design that chapel, as he died a few months later. But he’d be happy to learn the property has been restored.

Isabelle liked to create flower arrangements, so Wright planted a cutting garden for her in front of the home.

The Cutting Garden

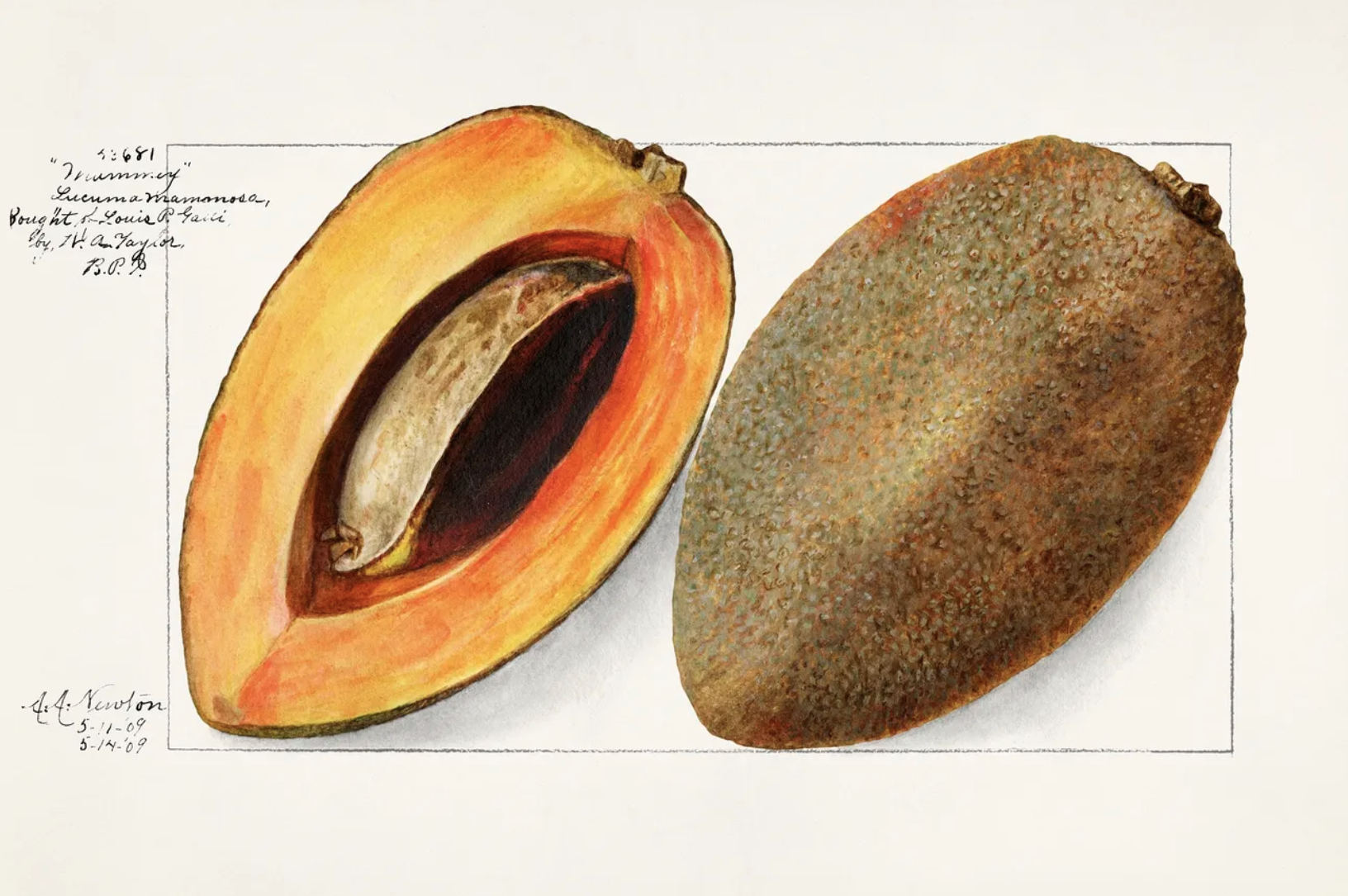

Our tour began with a walk through Isabelle’s garden. She was noted for her flower arrangements, so Wright designed gardens to accommodate her hobby.

Eventually, the Martins hired landscape architect Ellen Biddle Shipman, renowned for her naturalistic style, to revise Wright’s landscaping scheme. Shipman enhanced the garden for Isabelle, giving her flowers that would bloom in rotation from spring through fall.

The site also includes pine trees, which reminded Isabelle of summers at the Lake Placid Club in the Adirondack Mountains.

Beyond the cutting garden were the vegetable gardens, orchards for apple and pear trees and grapevines.

The house was approached from a diagonal driveway, which faced the sunset and helped make the narrow home appear larger.

The First Glimpse of Graycliff

Our initial view of the house took place between two stone markers, the original location of the driveway that led to the house.

The family owned eight and a half acres, but the plot where they wanted their summer home was two and a half acres. Further complicating matters, the spot atop the limestone bluff was just 250 feet wide. That’s very narrow for a 6,500-square-foot house.

But there was nothing Wright liked so much as a challenge. And one of the cool, oh-so-Wright elements is that you approach Graycliff at an angle. The Martins bought the adjoining property from their next-door neighbors, the well-to-do Rumseys. The driveway branches off of the Rumseys’ and perfectly faces the setting sun, which would be a vision for visitors arriving for a summer soirée.

The turnabout was made of yellow gravel — to complement the gold of the setting sun, of course.

Approaching from an angle had an added bonus: It made the narrow façade seem more stately and grand.

But the house itself wasn’t the main focus: Wright wanted the first glimpse to be of the lake; that was the true star of the show.

Horizontal lines almost always play a prominent role in Wright’s designs. For him, they draw a parallel to the ground, and in particular at Graycliff, the horizon and the surface of Lake Erie. The house becomes one with nature.

The roof is made with cedar shake shingles, each hand-painted. Wright didn’t like gutters, so the house doesn’t have any. He never was one to let practicality get in the way of aesthetics.

By creating a glass box of sorts, visitors could see through the home’s rectilinear form right out to the lake. At the time Graycliff was built, the area was undeveloped farmland, with nothing obstructing the view of the water.

The driveway curves around an artificial pond, but that wasn’t part of Isabelle’s plan. Once again, she wanted something that would evoke her beloved Adirondacks, and she requested a small hill covered with bushes and low trees. But Wright cleverly played the money card, and insisted that the pond would be less expensive. The idea is that this water feature would be an extension of the lake. Wright almost always got his way.

A large part of Wright’s design aesthetic involves incorporating colors and materials from the surrounding area. At Graycliff, sand from the shores of Lake Erie was mixed into the stucco to add another layer of texture, and the home’s red roof is meant to evoke the ferrous oxide in the Tichenor limestone on the cliff behind the house that bleeds a rust color.

Sand from the beach was added to the stucco façade and inspired its yellow hue. The cliff’s limestone, bleeding a rusty red that carries into the color of the roof, was also used to build the home.

Another design motif favored by Wright was cantilevers — and at Graycliff, he wanted to evoke the layers of limestone on the bluff.

His plans called for various additions, but his clients weren’t sold.

“The Martins were concerned about money, and they said to him, ‘We really don’t need this balcony; we don’t need the stone porch; we don’t need the porte cochère. Just a little awning would be great,’” our guide Gail tells us. “And then they go away on a trip — and when they come back, all that’s in process.”

When the Martins complained about these additions, Wright replied, “You don’t need them — but the house does.” Ever the egotist, Wright was always right, and he bristled whenever someone questioned his vision.

Stay by Sarah Braman, 2022, on the grounds of Graycliff

Sarah Braman: Finding Room

When we visited Graycliff, monumental modern sculptures by Sarah Braman were scattered about the grounds. These large geometric shapes made of concrete and brightly colored glass added a vibrant element of visual interest to the landscape. We enjoyed them, and hope that Wright would have appreciated them as well.

Duke peeks out of Sit, a 2022 sculpture by Braman — the first of her works we saw during our visit to Graycliff

Wally takes the name of the sculpture, Sit, literally.

That being said, we could have done without a couple of the ones inside the house. We’d have preferred to see the living room set up as it would have been when the Martins lived here — not emptied of some pieces of furniture to make way for Braman’s smaller-scale sculptures of domestic items and found objects, which struck us as disjointed.

The client actually wanted a hill here with trees — but Wright insisted on a small pond that would connect to the lake out back.

Entering Graycliff

Upon arrival, we passed through the porte cochère and entered the foyer. Immediately, you’ll notice one of Wright’s signature architectural techniques, known as compression and release. In the entry, the ceiling is low, and the smaller scale of the room creates a tension that propels you to move beyond it, into the larger living room, an open space with higher ceilings. To create the expansive double-height space, Wright used beams from nearby Bethlehem Steel.

Unlike Wright’s Prairie-style homes, which were concentric, with one large room off of which the others flowed, Graycliff is rectilinear. One room follows another, and Wright used compression to define transitions between these spaces without walls. By this time, he was moving into a style he referred to as organic architecture.

The stucco-covered walls used on Graycliff’s exterior continue into the interior, and provide a visual connection between the outdoors and indoors.

When the Graycliff Conservancy purchased the property in 1999, very few of the original furnishings remained. Many are reproductions, including the willow and reed pieces throughout the home. This type of furniture was very popular during the late ’20s and is thought to be similar to what Darwin and Isabelle saw when they vacationed in the Adirondacks. –Wally

Wright felt fireplaces were the heart of a home, and this one was built in the Adirondack style.

A Room-by-Room Tour of Graycliff

The Living Room

The living room is center stage. Floor-to-ceiling windows and doors open onto the front terrace and the backyard and span the length of the house. These walls of glass provide gorgeous views of Lake Erie and fill the interior with plenty of natural light. The focal point of the room is the monumental Adirondack-style stone fireplace with a mantle that nearly covers the north wall. Wright believed that the fireplace was the heart of the home. An unusual feature to this type of hearth is that logs were stacked on end, vertically. As a fire burned, it created a dramatic plume of flames.

One of the few materials used in the home that was not sourced locally was the cypress heartwood flooring from Florida — most likely chosen for its durability and beauty.

Curl up with a good book in the Fern Room, a cozy nook off of the living room.

The Fern Room

Adjacent to the living room is a cozy nook that served as a library and is known as the Fern Room — a great spot to curl up with a good book and admire the incredible views of the lake. The ceiling is lower here to establish a more intimate space. The floor is covered in flagstone that came from the city of Buffalo, which was, at the time, replacing its stone walkways with concrete.

Wright proposed that the window glass meet at the corners so as not to obstruct the view, but the Martins didn’t see the need for that additional expense. (He would later get his way at Fallingwater, a home built for Edgar and Liliane Kaufmann between 1936-1937 in Mill Run, Pennsylvania.)

The Sunporch

Beyond this, the floorplan flows into the sunroom, with rubber floor tiles. Originally a screened-in porch, cypress-framed windows were added to shield occupants from the intense winds coming off the lake.

The room functioned primarily as a music room. Isabelle had a paid companion who lived at Graycliff by the name of Cora Herrick, though the children called her Aunt Polly. She played the piano — one of the few original pieces of furniture remaining in the home. According to Gail, Darwin wrote in his diary how much he loved hearing music being played while he was working at his desk above.

Diners had great views at Graycliff — and got to avoid errant sparks flying out of the fireplace.

The dining room at Graycliff is around the corner from the living room.

The Dining Room

On the other side of the living room is an area that served as the dining room.

The table is positioned parallel to the wall so that guests could easily turn to enjoy the view of the lake — and also to avoid the errant sparks and embers that occasionally popped out of the fireplace.

All six bedrooms are found upstairs.

The Staircase

A cascading waterfall staircase made of maple leads to the home’s bedrooms on the second floor. This type of passage consists of two parallel flights of stairs joined by a landing that creates a 90-degree turn.

A dramatic window with a diamond shape at the top of the stairs

The architect’s signature use of rhythmic repetition can be seen in the home’s details. Wright noticed that the local limestone breaks off in geometric forms, so he gave a nod to these in subtle ways: octagonal door knobs and a diamond-shaped window at the apex of the staircase as well as light fixtures. This brings order and visual harmony to Graycliff.

Poor Darwin got stuck with the worst bedroom of the bunch.

Darwin, a workaholic, converted his porch into an office.

Darwin Martin’s Bedroom

Upon climbing the stairs, Darwin’s bedroom can be found to the right. Not only did Darwin not share a room with his wife, he was also assigned the worst of the bunch, to our minds. It’s smaller than most of the other bedrooms, though it does contain a small bathroom and sleeping porch.

Darwin converted the porch into an office, as he was a notorious workaholic.

The bedrooms feature one of the innovations at the time: olive knuckle hinges patented by Stanley Company that allow a recessed door to open all the way flat to the wall.

This sparse hallway led to the bedrooms and the back staircase.

We really liked Braman’s Her House (2019), which sat in Isabelle’s room, as it evoked the larger pieces on the lawn.

A guest room next to Isabelle’s room offered twin beds — and gorgeous views of Lake Erie.

Isabelle’s room had its own bathroom, a door out to a balcony and a walk-in closet — unheard-of in a Wright home!

Isabelle Martin’s Bedroom

At the top of the stairs and looking to the left is a monastic gallery, which has a similar set of windows as the living room below, and leads to a private wing with bedrooms. The first is a nice guest room, with Isabelle’s bedroom next door.

Wright despised closets. However, Isabelle was the client of record for the house and insisted he provide her with one. Her bedroom includes a walk-in closet where the bathroom was originally planned. But Isabelle wanted her bathroom to have a window, so it had to go on the lake side and required Wright to cut a hole into the chimney to accommodate her request.

A private terrace is accessible from Isabelle’s room, and she probably spent evenings there as direct sunlight would have been too much for her eyes to bear.

She might have been the hired help, but Aunt Polly sure had nice digs at Graycliff.

Aunt Polly’s Room

While she did get a nice bedroom, Aunt Polly was technically the help. Her room is a transitional space from that of the immediate family to the staff.

Cora remained in service from 1911 until Isabelle’s death in 1945. In 1929, when the Martins could no longer afford to pay her, Cora stayed on for room and board. After their mother’s death, the children took care of their dear Aunt Polly.

Even the servants had cute rooms at Graycliff.

The servants had their meals in a sunroom at the back of the house.

This cool sink came from Europe and was used exclusively by Isabelle for her flower arrangements.

The Pantry and Kitchen

Farther down the corridor are two bedrooms for the staff, as well as the back staircase that leads down to the staff sunporch and kitchen area.

The hammered metal sink in the pantry was imported from Europe and was used solely by Isabelle to arrange flowers from her cutting garden. The cook had to use the one in the adjacent kitchen, which faced the front yard instead of the lake.

On display within the built-in cabinets, another Wright trademark, behind Isabelle’s sink, are Larkin Soap products, including Buffalo china. Elbert Hubbard was Darwin’s brother-in-law and started the Arts and Crafts Roycroft movement in East Aurora, New York. He suggested to Larkin that consumers would be incentivized to purchase their product if they received a piece of china along with it. He was right, and the pottery ended up being quite successful.

In the cabinets, there’s also the Martins’ red and white wedding china and Indian Tree pattern china, which were gifted to the conservancy by the couple’s grandchildren.

Here’s the sink the cook used in the kitchen off of the pantry.

The stovetop and oven were all part of one piece of furniture.

The small yet functional kitchen contains another original piece, a hulking fridge from the Jewett Refrigeration Company, along with a freestanding prep station, sink and porcelain-glazed stove.

The Heat Hut held a boiler to heat both Graycliff and the Foster House. Then the priests used it to store wine and honey.

The Heat Hut

Sitting between the main home and the Foster House is the sunken red-roofed Heat Hut. The structure once held an oil boiler that provided steam heat to both houses. According to Gail, the Piarist priests used it to store wine and honey from the bees they kept on the property.

The Foster House, part of the garage at the Graycliff estate, was originally used by the chauffeur and his family.

The Foster House

The apartment above the garage was built for the chauffeur and his family. The original design was flipped so that the cantilever balcony would afford its inhabitants unobstructed views of the lake.

Shortly after the stock market crashed, the Martins couldn’t afford to keep the chauffeur out at Graycliff, so they sent him back to Buffalo, and their daughter Dorothy, and her husband, James Foster, moved in, spending summers there with their two children until 1941.

Wally and Duke on a balcony of the Foster House

There are quite a few bedrooms in the Foster House — but not much else, aside from a small sitting room and kitchen.

After Darwin’s death and the family’s financial troubles, Isabelle moved into the Foster House, staying in what was the gardener’s room, which had its own bathroom. The ever-particular woman liked to sit on the balcony — but she didn’t appreciate seeing the cars pull into and out of the garage. She contacted Wright, who acquiesced and moved the garage doors to the side and extended the wall.

Wright extended a wall to block out the view of cars coming and going from the garage for Isabelle.

“And she says, ‘While you’re at it, can you make me another bedroom up there?’” Gail tells us. So the apartment now has four bedrooms and a couple more balconies. Isabelle seems to have been the one person who could charm Wright into altering his original plans.

The seating out back helped hide the servants carrying picnic items down to the beach and back.

The Esplanade

Wright’s idea for the esplanade was to build a reflecting pool, cascading terraces and steps that led all the way down to the beach. But when the architect left the premises, Darwin contacted his friends at Bethlehem Steel to request a metal tower with steps like those his neighbors had. Not as pretty as Wright’s vision but certainly practical. It deteriorated, so there’s no longer any way down the beach.

Duke, Poppa and Wally enjoy the gorgeous day at Graycliff.

The access to the stair tower was visible, though, and again Isabelle complained about the view. When she was out on her terrace, she could see the servants coming and going. She felt this was unseemingly — that’s why they had a rear staircase, after all — so Wright constructed the overlook seating in such a way that the help could go about their business while remaining out of sight.

Saving Graycliff

When the Martin family decided to sell the property, the person who wanted to buy it was a developer who built the condominiums that are now next door. He planned to demolish Graycliff — who needs a historic home when you can get top dollar for lakefront condos?

Thankfully, a group in Buffalo came to the rescue, forming the Graycliff Conservancy. In 1999 they received a grant, and the conservancy was able to purchase the property.

The renovations began, wrapping up in 2019 and costing about $10 million.

There are plans to build a new eco-friendly visitors center to replace the current one, which was built by the priests as a gymnasium for the children.

Restored back to its 1926 splendor, Graycliff exemplifies Wright’s philosophy of living in harmony with nature. If you’re in the Buffalo area, stop by for a visit. As with all of Wright’s homes, they have to be seen to be fully appreciated. –Duke

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Graycliff

Graycliff

6472 Old Lake Shore Road

Derby, New York 14047

USA