El Cubo, as locals call it, a museum located in Málaga’s vibrant port, is anything but boring. This dazzling structure, designed by Daniel Buren, houses a captivating collection of avant-garde art.

The surprising multicolored cube on Málaga’s port is a branch of the Centre Pompidou, Paris’ modern art museum.

When I was in high school, my French class took a trip to Paris, and it was there that I first laid eyes on the Centre Pompidou. The building’s exterior, with its industrial ductwork winding up like a scarlet-bellied serpent, and a pair of cherry red lips spouting water in the fountain, captivated my youthful imagination.

But if you thought the Centre Pompidou was just that quirky building in Paris, think again. The avant-garde behemoth has spawned a sibling in Málaga, Spain; the city famous for its hometown homeboy, Picasso, and amazing Moorish landmarks like the Alcazaba and Gibralfaro, got a bit of Parisian modern art chic.

“The project was initially conceived as a limited five-year venture.

It has proven so successful, Málaga has decided, with Paris’ agreement, to extend its lease until 2034.”

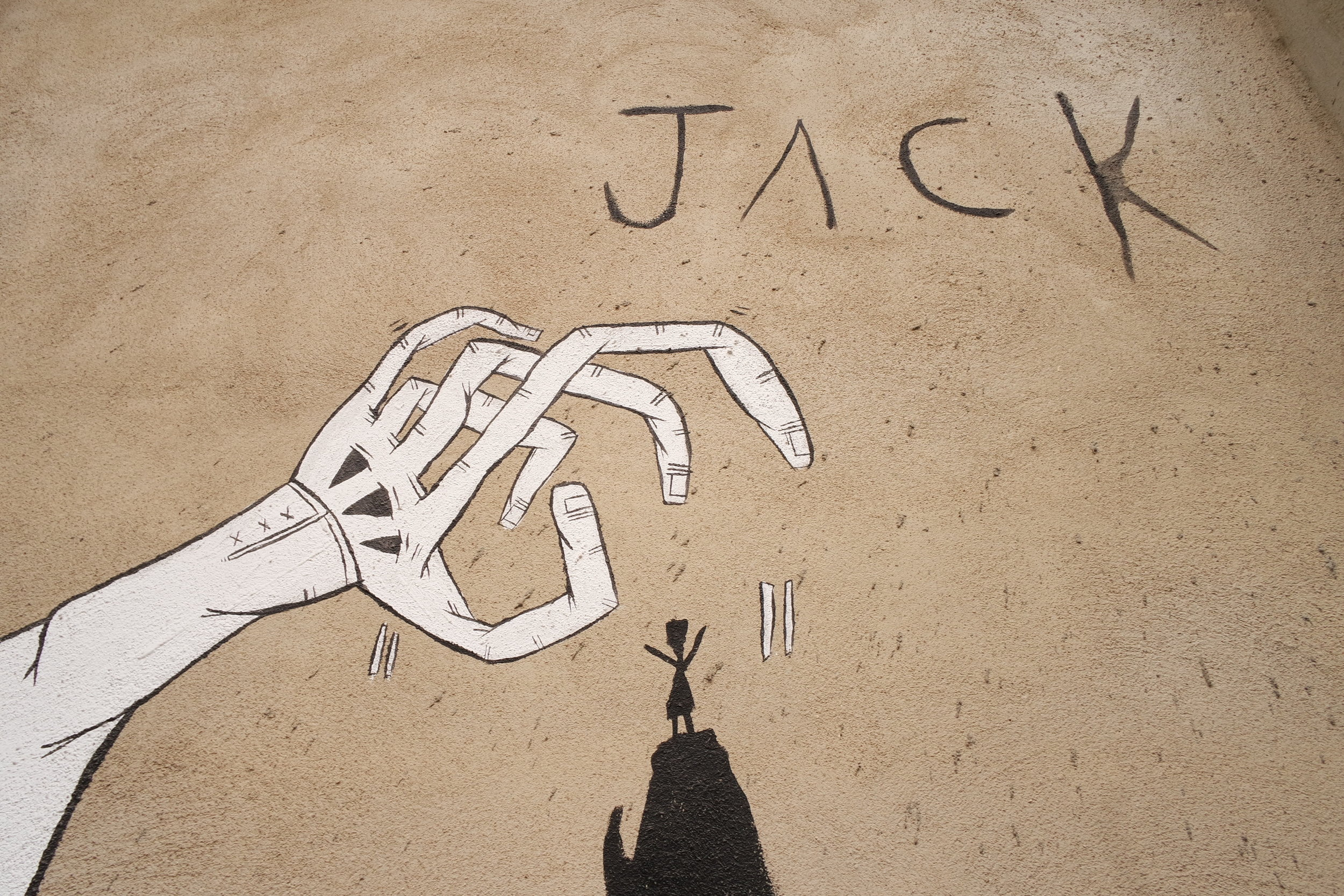

Various sculptures are put on temporary display outside of the museum.

Why Málaga?

The project was initially conceived as a limited five-year venture between Málaga’s mayor, Francisco de la Torre, and the Centre Pompidou’s president, Serge Lasvignes. The French institution agreed to lend its brand name, curatorial expertise and artworks from its Paris HQ to the chic port city of Málaga in the South of Spain. This cultural experiment provided the perfect canvas for the Centre’s first foray outside France. It has proven so successful, Málaga has decided, with Paris’ agreement, to extend its lease until 2034.

Daniel Buren came up with the whimsical design.

The Colorful Genius and Bold Design of Daniel Buren

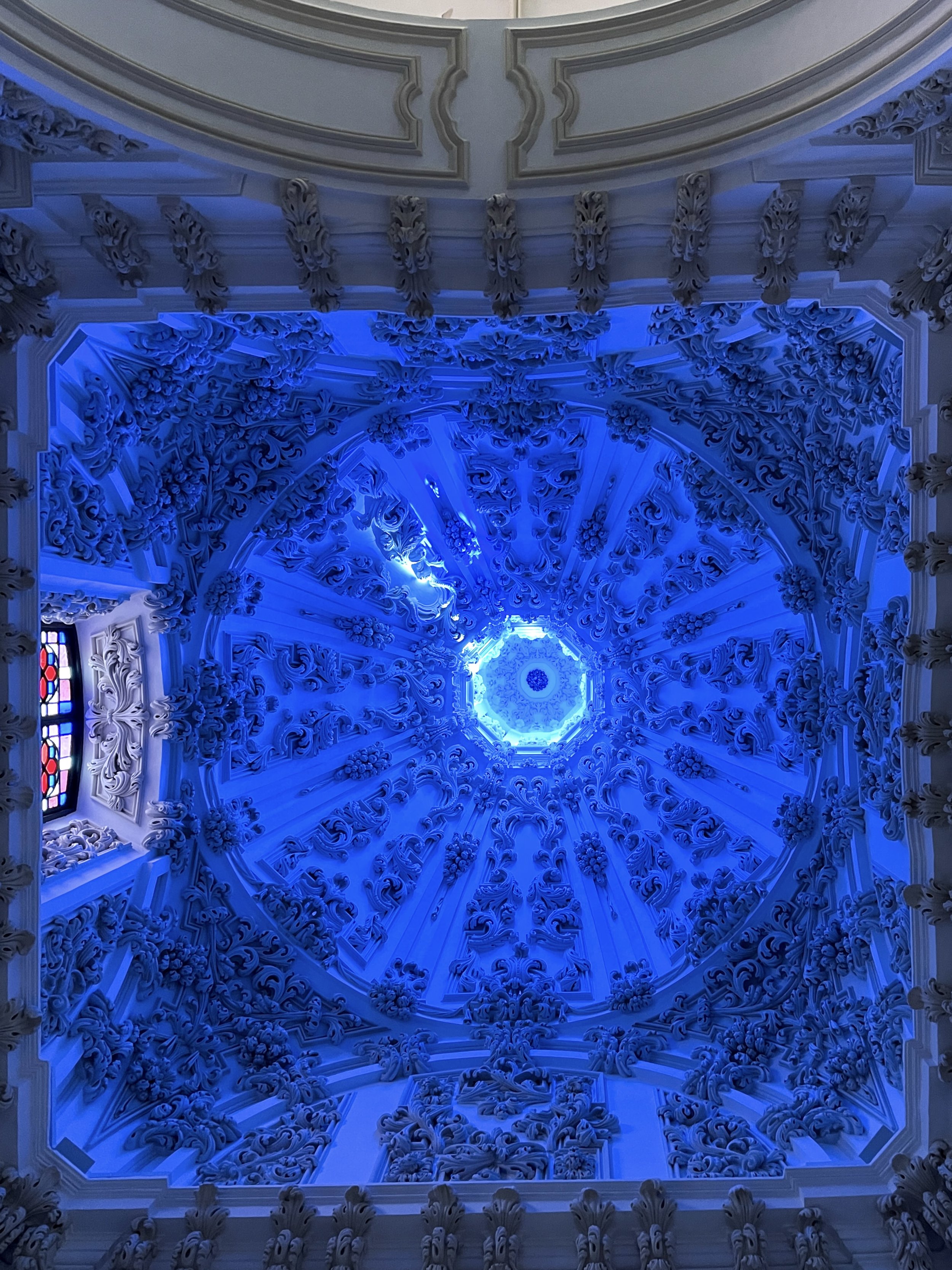

The Centre Pompidou Malaga isn’t just a museum — it’s a statement. You can’t miss it. Its design is as bold as its Parisian parent’s. But instead of resembling a building turned inside out, the Pompidou Málaga looks like a giant Rubik’s Cube made of glass was plopped down in the city’s port. It’s the brainchild of French artist Daniel Buren, renowned for his use of bold colors and geometric patterns.

Buren takes an in situ approach, which is a fancy way of saying he integrates his pieces directly into their environments, creating site-specific art that interacts with its surroundings. And that’s certainly the case with El Cubo (the Cube), as the Málaga Pompidou is affectionately called. A transparent, multicolored structure serves as the entrance to the subterranean museum space. Its design is a sharp contrast to the traditional Spanish architecture around it, making it a standout landmark.

Buren’s use of color and light transforms the cube into a dynamic piece of art, changing its appearance with the movement of the sun and the seasons. It’s as much a work of art as those found within. Try walking by at different times (sunrise or night, in particular) to see how light plays upon the façade.

The museum opened in 2015 for a short stint — but it has obviously done well enough to extend its agreement through 2034.

The Pompidou Málaga’s Opening Act

When it first opened in 2015, the Centre Pompidou Málaga was met with a mix of excitement…and skepticism. Art critics and the public alike were curious about how this Parisian transplant would fit into the cultural tapestry of Málaga. But The Guardian gushed, “The Centre Pompidou in Málaga represents a bold cultural experiment, bridging the artistic ethos of Paris with the vibrant spirit of southern Spain.”

Meanwhile, El País highlighted the architectural contrast: “Daniel Buren’s colorful cube stands as a beacon of modernity against Málaga’s historic skyline, symbolizing the city’s commitment to contemporary art.”

Wally and Duke can find modern art to be hit or miss — but the Centre Pompidou Málaga was filled with cool, thought-provoking works.

Art and Exhibitions at the Pompidou Málaga

But the Centre Pompidou in Málaga isn’t just a pretty cube — it’s a treasure trove of modern masterpieces that would make any modern art lover swoon.

The permanent collection is a curated selection of works from the vast repository of the Centre Pompidou in Paris. It spans the 20th and 21st centuries, showcasing iconic pieces from celebrated artists such as Francis Bacon, Frida Kahlo, Joan Miró — and, por supuesto, Pablo Picasso.

Lipstick by František Kupka, 1908

Bal au Moulin de la Galette by Raoul Dufy, circa 1943

Children and Lanterns by Tadé Makowski, 1929

These works are arranged thematically rather than chronologically, providing visitors with a fresh perspective on modern art movements and their interconnectedness. The themes often explore major artistic movements and their cultural contexts. You might find rooms dedicated to Cubism, Surrealism or Abstract Expressionism. This approach not only highlights the evolution of styles but also the ongoing dialogue between artists across different periods and geographies.

Hollywood Sleep by Jean Cocteau, 1953

Suddenly Last Summer by Martial Raysse, 1936

During our visit, we caught the temporary exhibition Un Tiempo Propio (or Time for Yourself for those of you who don’t speak Spanish), a spirited rebuke of the relentless demands imposed by our digital calendars. Showcasing the works of 90 artists, the exhibit delved into the theme of leisure, encouraging a pause from the daily grind. It served as a refreshing reminder to reclaim our time and disconnect, if only momentarily, from the buzz of notifications and schedules — a true celebration of the art of relaxation and the simple joys of free time.

We Stopped Just Here at the Time by Ernesto Neto, 2002

One of our favorite exhibits in Un Tiempo Proprio was by Ernesto Neto, the Brazilian maestro of the bizarre: We Stopped Just Here at the Time. This artwork was a captivating display of suspended bags filled with aromatic herbs like rosemary, parsley and thyme. The installation reminded me of a forest of hanging testicles (paging Doctor Freud!), creating a whimsical and immersive environment that invited visitors to bask in the earthy fragrances and stare, mesmerized, at the organic forms swaying gently.

Ettore Sottsass’ Flying Carpet Armchair

Sottsass’ designs are somehow retro and modern at the same time, like this minimal mint green cabinet.

We also enjoyed the Ettore Sottsass: Magical Thinking exhibition, which showcased over 100 pieces of Sottsass’ groundbreaking work. These retro-futuristic items in bright colors reminded me of Fisher-Price children’s toys, highlighting the designer’s playful approach. Sottsass was a key figure in the Memphis movement of the 1980s, which revolutionized design with its bold use of color, geometric shapes and whimsical patterns. The postmodern movement rejected minimalism in favor of a more expressive, emotionally engaging style. The exhibit captured this ethos, blending fun and sophistication in a way that made each piece feel both nostalgic and cutting-edge.

The Basilico Teapot

Cherry Model Teapot

it wouldn’t be a modern art museum without a creepy clown.

Discovering the Unexpected at the Pompidou Málaga

Duke and I were thoroughly impressed with the Centre Pompidou Málaga, where we encountered a captivating variety of art that was both thought-provoking and immersive. We spent a delightful couple of hours there, exploring the museum’s strange and intriguing pieces, each offering a unique perspective on modern art. The experience exceeded our expectations and was a refreshing contrast to what we consider the less inspiring exhibitions that the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago has featured in recent years.

The variety of exhibits at the Centre Pompidou Málaga ensures that whether you’re a seasoned art critic or a curious traveler, there’s something that will capture your imagination and perhaps even challenge your understanding of what art can be. So, the next time you find yourself in Málaga, make sure to descend into El Cubo — you just might discover your new favorite artist or a whole new way of looking at the world. –Wally

There are lots of different areas to explore at the Centre Pompidou Málaga, but they can all be done in a couple of hours.

The lowdown

The Centre Pompidou in Malaga is located in the city’s vibrant port area, making it easily accessible.

Hours of operation

Monday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday: 9:30 a.m. to 8 p.m.

Saturday and Sunday: 9:30 a.m. to 8:30 p.m.

Tuesday: Closed (except on public holidays)

Holidays: Open with extended hours; always check the official website for up-to-date holiday hours.

Admission costs

General admission: €9

Reduced admission: €5.50 (available for seniors over 65, students under 26 and large families)

Free admission: For children under 18, unemployed individuals and visitors with disabilities (with one companion)

Special free hours: On Sundays from 4 p.m. to closing, and all day on certain designated dates (such as International Museum Day)

Exit through the gift shop.

Tips for visitors

Advance tickets: It’s a good idea to purchase tickets online in advance to avoid long lines, especially on weekends and holidays.

Guided tours: Consider booking a guided tour to get the most out of your visit. Tours are available in multiple languages and offer deeper insights into the exhibitions.

Accessibility: The Centre Pompidou is fully accessible to visitors with disabilities. Elevators and ramps are available, and wheelchairs can be borrowed at the information desk.

Photography: Photography without flash is allowed in most areas.

Coat/bag check: Leave your bags and coats to make it easier to enjoy the exhibits unburdened.

Gift shop: Exit through the gift shop, where you can pick up some cool souvenirs or gifts.

Centre Pompidou Málaga

Pasaje Doctor Carrillo Casaux

Muelle Uno

Puerto de Málaga

29001 Málaga

Spain