Explore the Malaga Museum, a tribute to the past that feels completely current in the Palacio de la Aduana.

The Malaga Museum has an impressive fine art collection, including Gladiadores/La Meta Sudante (Gladiators/The Meta Sudans) by José Moreno Carbanero from 1882.

Málaga, one of the world’s oldest cities, isn’t short on sunlight, history or art. With its dizzying array of attractions, the city offers much to explore. The Centro Histórico, a pedestrian-friendly area, is home to many notable sites, including the Museo de Artes y Costumbres Populares (Museum of Popular Arts and Traditions), the Renaissance-style Catedral de Nuestra Señora de la Encarnación (Málaga Cathedral) and modern art institutions like the Centre Pompidou Málaga. Nearby, the Alcazaba fortress stands guard on the hillside above a Roman amphitheater, connected to the Gibralfaro Castle by a fortified walkway.

The building that houses the museum is called the Palacio de la Aduana and was the customs house for the busy port.

History of the Museum of Málaga

A standout among these cultural treasures is the Museo de Málaga (Museum of Málaga). Housed in the Palacio de la Aduana (Customs House), this magnificent 17th century Neoclassical landmark is nestled between the verdant Parque de Málaga and the Ayuntamiento de Málaga (Málaga City Hall) in the heart of the Old Quarter.

Its construction was initiated in 1787 under King Charles III in response to Málaga’s growing maritime trade, and was conceived by architect Manuel Martín Rodríguez, who drew inspiration from Madrid’s palatial Real Casa de la Aduana (Royal Customs House).

“With over 2,000 works of art and more than 15,000 artifacts in its archaeology collection, the museum offers a vast and captivating chronicle of Málaga’s history.”

Although the project actually started in 1791, it encountered several delays, including Napoleon’s failed attempt to conquer Spain during the Peninsular War, which pushed its completion date to 1829.

Nearly two centuries after its construction, the renovated venue reopened to the public, preserving the building’s original character while updating its interior to meet 21st century standards for accessibility.

The museum unites the collections of the Real Academia de San Telmo (Saint Elmo Academy of Fine Arts) and the Museo Arqueológico de Málaga (Málaga Archaeological Museum) under one roof. With over 2,000 works of art and more than 15,000 artifacts in its archaeology collection, the museum offers a vast and captivating chronicle of Málaga’s history.

A mix of unmarked artifacts, including green glazed pottery and religious statuary, is displayed on wooden shelves inside the Visitable Warehouse section of the Museum of Málaga.

Ground Floor Visitable Warehouse

After paying the admission fee of €1.50 (approximately $1.63) per person, Wally and I began our visit on the ground floor with the Almacén Visitable (Visitable Warehouse), a storeroom of sorts, where objects are organized by time period and displayed in drawers and on shelves and wooden platforms. (It reminded us a bit of the ramshackle Egyptian Museum in Cairo.)

A collection of Hellenistic pottery, including terracotta heads, pig figurines and feet fills one of the display cabinets.

Among the artifacts were ancient vases, pots and fragments of centuries-old marble column capitals, feet, torsos and heads, displayed alongside 19th century oil paintings culled from the Fine Arts collection.

The warehouse is fun to explore, with its jumble of marble architectural fragments, a pair of Christ figures missing their crosses and a cathedral bell.

Look for the scale models, including one of the Roman amphitheater and (we think) the interior of Málaga Cathedral.

Wally and I oohed and ahhed over a scale model of the Alcazaba and Gibralfaro. In another part of the room, a glass display case held several devotional sculptures, including religious images of the Virgin Mary, underscoring the reverence and care with which these objects are treated.

A view of the palatial courtyard of the Museum of Málaga. The classical terracotta busts were added in 1885 to commemorate Queen Isabella II’s son Alfonso XII.

Central Courtyard

Following our tour of the storehouse, we wandered through the expansive central courtyard, graced with palm and orange trees, a fountain and informational panels recounting the building’s history, including Queen Isabella II’s visit in 1862. Terracotta busts, added to honor her son Alfonso XII’s visit 23 years later, have adorned the uppermost balustrade of the courtyard gallery ever since.

When we visited, there was a special exhibit on the hometown hero Picasso.

Special Exhibit on Picasso

The port city is the birthplace of Pablo Picasso and, during our visit, it was hosting the exhibition La presencia de Picasso (The Presence of Picasso) to mark the 50th anniversary of his death.

A selection of lithographs from Picasso’s Faunes et Flore d’Antibes series at The Presence of Picasso exhibition.

On a separate note, the Museum of Fine Arts previously occupied the Palacio de Buenavista (Buenavista Palace), but it was unceremoniously packed up and placed in storage in 1997 to make way for the Museo Picasso Málaga (Málaga Picasso Museum).

Fauno Blanco Tocando el Aulós (White Faun Playing the Flute) by Pablo Picasso, 1946

The exhibition featured lithographs from the Faunes et Flore d’Antibes series and engravings from Deux Contes, both drawn from the Fine Arts permanent collection. Wally, a big fan of mythology (and the male form), especially liked the collection.

A glimpse of what awaits you at the beginning of the Fine Arts section of the museum.

First Floor: Fine Arts

Upstairs (keep in mind that in Europe the first floor is what we Americans would call the second floor), the Fine Arts section covers a broad spectrum of 19th century artworks, including pieces by old masters like Antonio Muñoz Degrain, Bernardo Ferrándiz y Bádenes, Fernando Ortiz y Comarcada, José Gutiérrez de la Vega and Pedro de Mena, among others. It also features works by prominent members of the Málaga School of Painting, such as Alfonso Ponce de León y Cabello, José Suárez Peregrin and Pedro Sáenz Sáenz.

Los Saltimbanquis (The Acrobats) by José Suarez Perigrín, 1932

El Juicio de Paris (The Judgment of Paris) by Enrique Simonet y Lombardo, 1904

Después de la Corrida (After the Bullfight) by José Denis Belgrano, 1890

Estudio de Anatomía Masculina (Study of the Male Anatomy) by Bernardo Ferrándiz y Bádenes, 1862

Tarquin y Lucrecia (Tarquin and Lucretia) by José López García, 1988

Alegoría de la Historía, Industría y Comercio de Málaga (Allegory of the History, Industry and Commerce of Málaga) by Bernardo Ferrández and Antonio Muñoz Degrain, 1870

The first piece you’ll see as you enter these galleries is a maquette, a final study for the ceiling of the Teatro Cervantes by the Valencian-born painter Bernardo Ferrándiz. In 1870, he and Degrain were commissioned to decorate the theater. Ferrándiz depicted himself as Mephistopheles, the demon who barters for Faust’s soul, on the stage set.

The female figure, possibly a symbol of the city, sits atop a shrine holding a caduceus— a symbol associated with Mercury, the god of commerce and prosperity. Other aspects of the city’s booming cultural and economic success, including agriculture, industry, transportation and fishing, highlight its strategic location as a trading port.

However, to me, some of the most interesting pieces came from religious institutions. Like the Museo de Bellas Artes de Córdoba, this museum’s collection includes significant works of art, images and architectural elements seized from the deconsecrated monastic properties, including the ex-convents and monasteries of the Poor Clares of Santa Clara, San Bernardo, La Merced and San Pedro de Alcántara.

Mudejar ceiling corbels

Next, you’ll notice a set of four carved oak corbels, or brackets. They originally adorned the ends of timber beams in the Convent of La Merced and became part of the academy’s collections in 1915. These architectural elements illustrated the sins and vices parishioners were expected to renounce before entering the holy space.

Head of Saint John of God by Fernando Ortiz y Comarcada, circa 1755-1765

Fernando Ortiz y Comarcada’s sculptural style was greatly influenced by Pedro de Mena — in fact, for many years, this work was attributed to Mena. However, documents found for the production of four sculptures at Parroquia Santiago Apóstol in Málaga confirmed Ortiz as the artist. This head is the only surviving piece from that series, which was largely destroyed during the protests of 1931. An anonymous citizen saved this from the flames and left it at the parish door in a basket, ensuring that future generations could appreciate its artistic quality.

Ecce Homo by Pedro de Mena, circa 1676-1680

Throughout his lifetime, Pedro de Mena was in high demand, securing a steady stream of public and private commissions across Spain and Latin America. It’s believed that Ecce Homo came from the estate of El Retiro in Málaga and was first owned by Bishop Alonso de Santo Tomás, who hired Mena to carve images for his private oratory while the sculptor was working for the bishop’s order at the Monastery of Santo Domingo.

(Postrimerías) A Moro Muerto, Gran Lanzada, or (Dying Moments) Kicking a Man While He’s Down by Bernardo Ferrándiz y Badenes, 1881

This small painting might seem unremarkable at first glance, but it has an interesting story behind it. The artwork was inspired by an actual event that forever changed the artist’s life. Bernardo Ferrándiz y Badenes had a physical confrontation with Juan Nepomuceno Ávila, a fellow academy member, municipal architect and close friend of the Marquis of Salamanca. The dispute arose because Ávila denied financial support to the San Telmo Fine Art School, where Ferrándiz was the director at the time.

Ávila used the incident to have Ferrándiz expelled from the institution. Ferrándiz subsequently was accused of attempted murder and imprisoned. Although the exact details of the altercation remain unclear, the event left Ferrándiz shaken. The once-prominent artist faced social ostracism, which plays out in his artwork, where he depicted himself as the skeleton of a cat, with Ávila as a mouse. He inscribed the following on the frame: “Fierce king, yesterday I gave you my laws to respect, and today, with death upon me, even you come to trample the dust of what I was.”

Additionally, the museum has a small collection of Spanish modern art up to the 1950s, including works by José López García, José Moreno Villa, Juan Fernándo Béjar and, yes, Picasso.

This Italo-Corinthian helmet most likely belonged to a high-ranking warrior. It was unearthed in 2012 by archaeologists excavating a site between Calles Jinete and Refino in Málaga’s historic quarter.

Second Floor: Archeological Section

The second floor (third floor to you Americans) galleries focus on archaeology, with the first two rooms dedicated to the private collection of Jorge Loring Oyarzábal and his wife, Amelia Heredia Livermore, also known as the Marquis and Marquesa de Casa Loring.

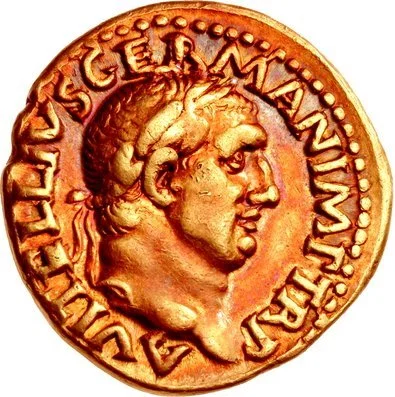

The Lorings had a passion for antiques and collecting. One of their most important acquisitions was several pieces from the collection of 18th century Córdoban antiquarian Pedro Leonardo de Villacevallos, which included capitals from Medina Azahara, Umayyad-period tombstones and sculptural relics from Ancient Rome.

A collection of marble busts, and funerary plaques from the Villacevallos collection acquired by the Lorings

This 18th century religious sculpture, depicting the realistic severed head of Saint John the Baptist, is paraded through the streets of Málaga during Holy Week.

A mosaic fragment depicting Priapus, the son of Venus and Bacchus. Commonly shown with a massive erection and basket of fruit, it’s no surprise he’s a god of fertility.

The remaining halls cover a vast historical timeline, showcasing how each civilization — from prehistory through the Phoenician, Roman, al-Andalus and Christian Reconquest periods — contributed to the city’s cultural mosaic. In recent decades, artifacts unearthed during construction and in excavations carried out by the University of Málaga have been added to the collection.

A detail of the center of a 1st century Roman mosaic depicting the goddess Venus surrounded by a menagerie of birds.

Speaking of mosaics, a 1st century floor panel depicting the birth of Venus, the goddess of love, sex and beauty, takes center stage in the museum’s Roman galleries. Discovered in 1956, it was found lining the floor of a Roman villa in the nearby town of Cártama. This impressive mosaic measures 13 by 20 feet (4 by 6 meters). It shows the naked goddess reclining on a giant scallop shell above a couple of dolphins.

The 2nd century Roman statue known as La Dama de la Aduana, discovered while digging the foundations of the museum in 1791, welcomes visitors at the entrance.

A Trip Back in Time at the Museo de Málaga

To sum up our experience, the Museo de Málaga was more than just a tourist attraction. It was a journey through epochs that celebrates Málaga’s multifaceted identity and enduring spirit. Its artworks and archaeological objects are well organized and clearly marked in both English and Spanish. As you walk through its halls, the city’s colorful history comes alive. –Duke

Museo de Málaga

Plaza de la Aduana 1

29015 Málaga

Spain