The Great Mosque of Córdoba, a UNESCO World Heritage site in Andalusia, endures as a monument to Spain’s cross-cultural harmony.

Ancient Rome, Islamic Spain and Catholicism all come together in the breathtaking Mezquita in Córdoba.

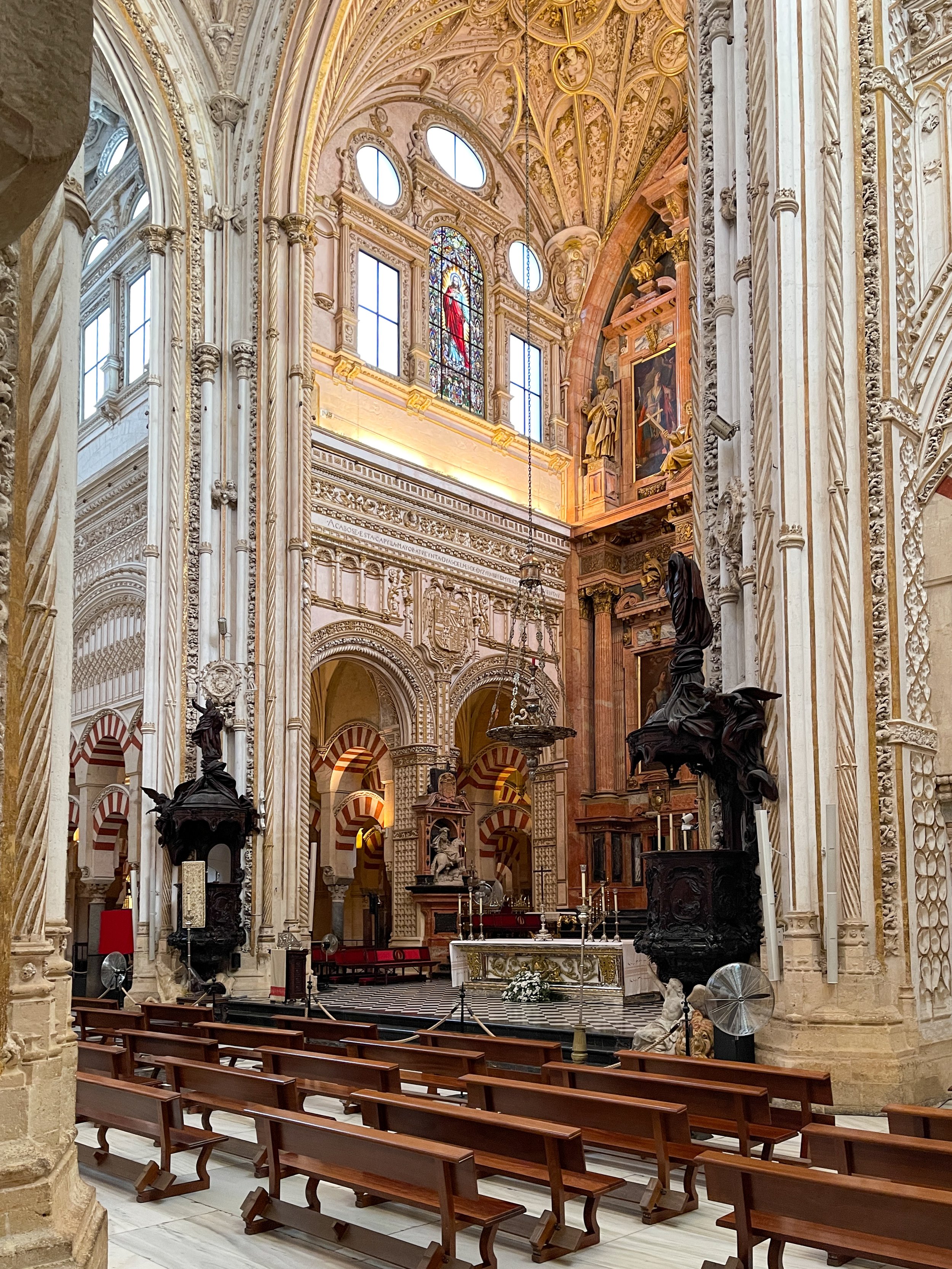

It’s all about those arches. They seem to multiply into infinity, creating a seeming mirror maze of red and white latticework. It’s one of the iconic images that make Córdoba a must-visit stop on any trip to the south of Spain.

The Mezquita in Córdoba is the perfect symbol of what Duke and I love about Andalusia. You have Roman influences, Islamic stylings and a Roman Catholic overlay. It’s a magical part of the world, where these three cultures blend together into architecture that can’t be found anywhere else but southern Spain.

Case in point: Córdoba’s Great Mosque, known as the Mezquita, perpetually rising from its ashes like a phoenix over 10 centuries through a fascinating interplay of Roman, Islamic and Christian construction.

“King Carlos I lamented his decision to allow the construction of the cathedral, saying, “They have taken something unique in all the world and destroyed it to build something commonplace.”

That’s a bit harsh.”

Parts of the massive structure’s exterior retain their Islamic architecture.

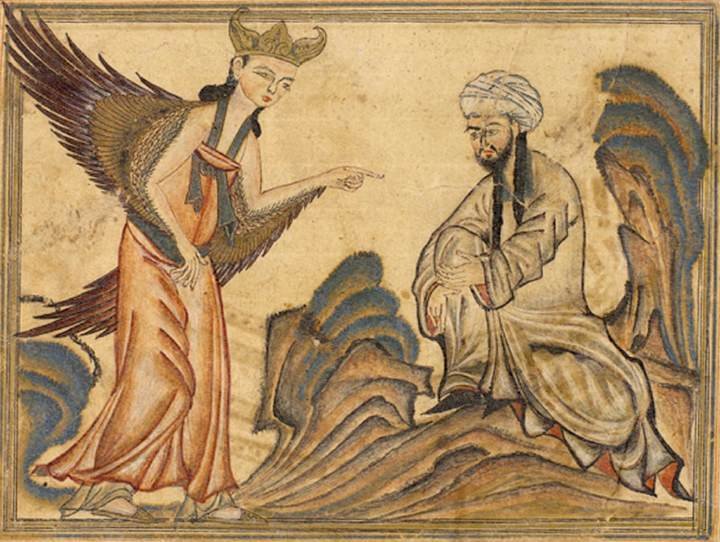

Abd ar-Rahman and the Start of the Mezquita

To understand Córdoba and the history of this amazing structure, we must travel to the Middle East and meet Abd ar-Rahman I, a member of the Umayyad dynasty in Damascus, Syria. Things aren’t going so well for the prince. His family was massacred by the Abbasids, rivals for Islamic rule, and Abd ar-Rahman fled, hiding out in the farthest corner of the Muslim world. That is, the south of Spain.

He ended up in Córdoba. After wresting control of the city from the Visigoths, Abd ar-Rahman began eyeing the church of San Vicente, the largest in town. Not surprisingly, it had been been built upon the ruins of a Roman temple (you’ll notice a trend). Abd ar-Rahman purchased half of the church from the Christians to start, before eventually buying the rest.

Then, in 786 CE, he tore down the church to construct his most important project: a massive cathedral mosque.

The History of the Mezquita

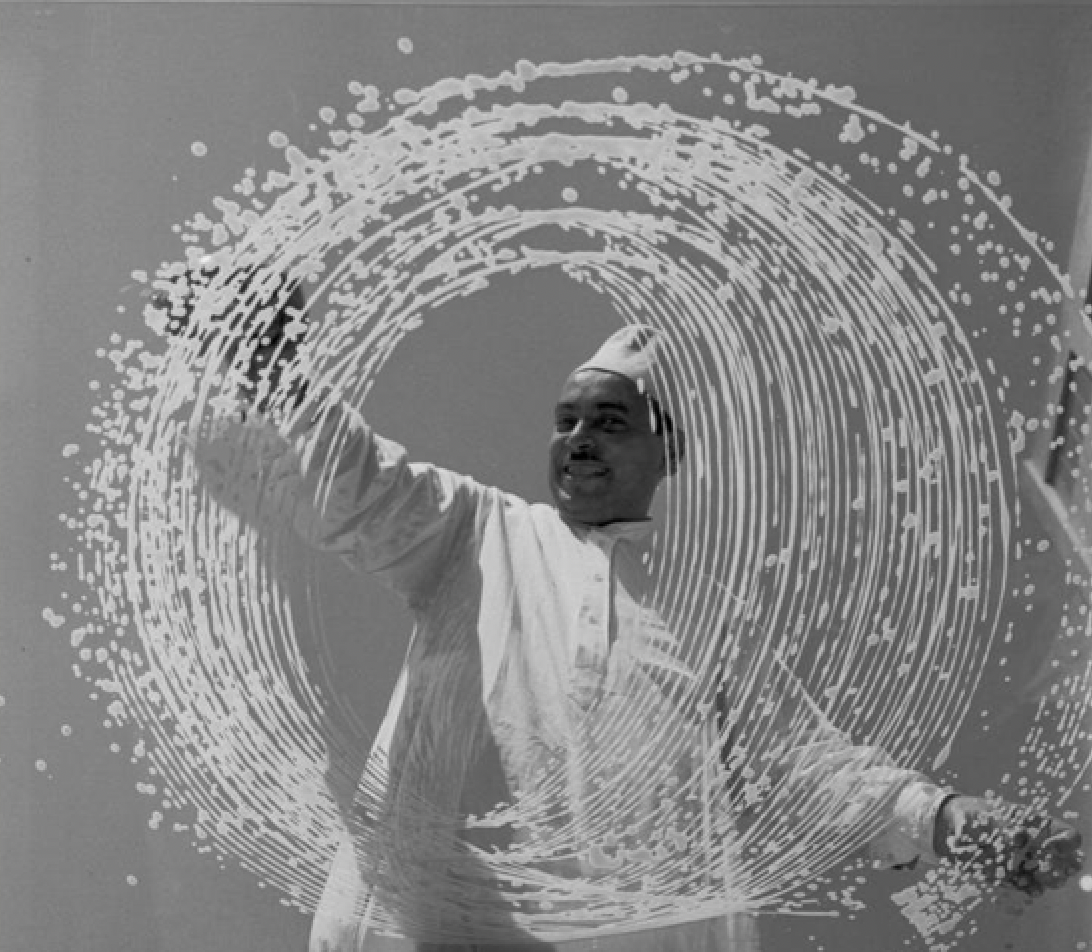

The designers ran with those mesmerizing horseshoe arches, a style borrowed from the Visigoths, placing them atop recycled columns from the original Roman ruins. The distinctive red and white is a result of alternating brick and stone. The repetition of the arches was an attempt to evoke the infinite nature of Allah. I’d say they succeeded.

“The aesthetics of the new Cordoban mosque, to which Muslims from far and wide throughout history would forever write odes, was typically Anadusian from the start: part adaptation of local, vernacular forms and part homage to Umayyad Syria, forever the source of hereditary legitimacy,” María Rosa Menocal writes in The Ornament of the World.

“The Cordoba mosque continued to be built, and added to, for the next 200 years, until nearly the year 1000, but the characteristic look of the place, the horseshoe arches that sit piggybacked on each other, themselves dizzyingly doubled in alternations of red and white, were established from the start,” she continues.

Abd ar-Rahman II, great-grandson of his namesake (792-852), expanded the Great Mosque and added a new mihrab, a niche where Muslims face to pray.

Then, Abd ar-Rahman III (891-961) enlarged the patio and built a new minaret, which stood 130 feet (40 meters) tall.

All those red and white arches, designed to mimic infinity, are truly hypnotic.

His son, Al-Hakam (915-976), continued his father’s work — in fact, he’s responsible for the most impressive renovation of the space. He had new columns built, alternating pink and blue marble. Domes were added to let in light, while painted wood beams decorated the ceiling. The 11 naves were extended, and a larger qibla wall built (this is supposed to be the cue to facing Mecca, but more on that later). Oh, and there was a secret passage for the caliph to enter the mosque from his adjoining palace.

Gorgeously painted wooden ceiling beams

At the end of the 10th century, Córdoba had become a bustling city. To accommodate the growing population, Almanzor (938-1002) made the courtyard bigger and added eight naves. These are the most austere of the bunch. Ultimately, the Mezquita could hold 40,000 worshippers. It was the largest mosque in the world at the time.

It wasn’t just used for prayer, though; it was the center of Cordoban life. Judges made rulings near the mihrab. Teachers taught children under the arches. And traveling pilgrims were allowed to sleep there.

Religious Reversal: From Mosque to Cathedral

In 1236, King Ferdinand III conquered Córdoba, returning the city to Christian rule. The mosque transitioned to the cathedral of Santa María, even as many Islamic elements endured. The Main Chapel is located under the skylight.

King Henry II built the Royal Chapel to provide tombs for Castilian monarchs. This was done in the Mudéjar style, a delightful blend of Gothic and Islamic, using Muslim architects and carpenters.

An area with pointed arches was built to give light and height for the choir as well as the church bigwigs.

The structure remained largely the same until 1528, when King Carlos I gave permission to tear out the center of the mosque to build a proper cathedral, much to the dismay of many in Córdoba. Turns out he ended up agreeing with them. When the king visited, he lamented his decision, saying something along the lines of, “They have taken something unique in all the world and destroyed it to build something commonplace.”

That might be a bit too harsh. This is still one impressive place of worship.

The choir stalls were built in the Baroque style of mahogany wood from Cuba. As in many Catholic churches, naves line the walls, containing small chapels.

(FYI: Much of this history comes from a kid’s book we bought in town: La Mezquita de Córdoba by Manuel González Mestre, with fun illustrations by Jacobo Muñiz López.)

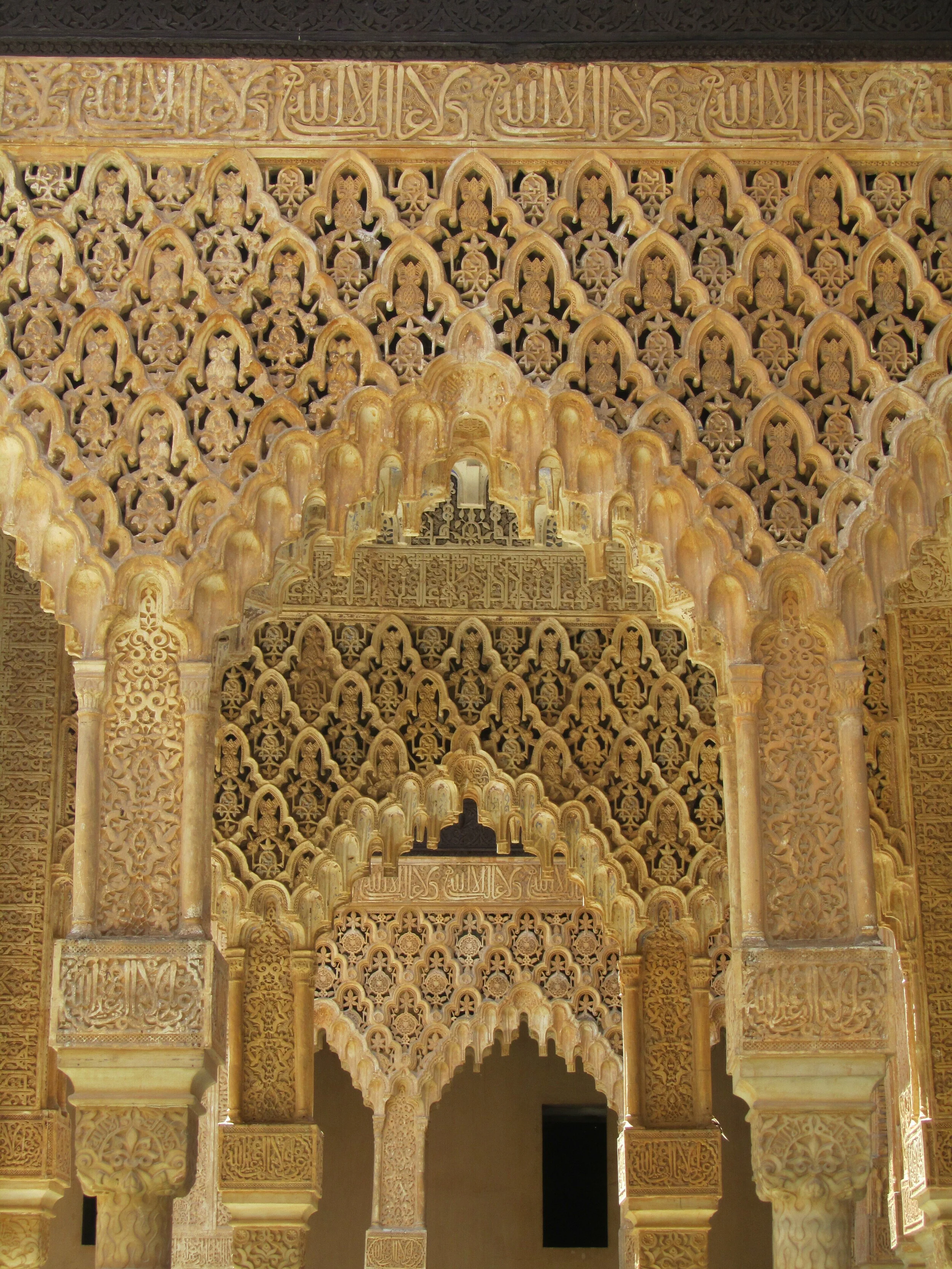

The Mihrab: Where Intricate Beauty Meets Spiritual Significance

While wandering the Mezquita, look for the mihrab. Among the monument’s ornate riches, none capture the cross-cultural transformation quite like the exquisite mihrab, located along the back wall on the right side. It’s considered the most sacred part of a mosque.

Strangely enough, though, this qibla doesn’t actually indicate Mecca. Instead, it faces south. One theory is that it was a reference to the direction where Mecca would be from Abd ar-Rahman’s hometown of Damascus. Then again, it’s also thought that the streetscape didn’t allow for the qibla to face east as it should have, and instead was chosen to align with the Guadalquivir River.

When Córdoba was conquered by the Christians, they not only repurposed the mosque, they also recognized the mihrab’s beauty and spiritual importance — and actually preserved it! It’s a surprising moment where two faiths coexist within the same sacred space.

Intricate mosaics, geometric patterns and calligraphy intertwine to create a tapestry of colors and shapes that leaves visitors in awe.

The Patio de los Naranjos: An Oasis of Tranquility

Chances are you’ll begin your exploration of the Mezquita in the Patio de los Naranjos, the Courtyard of the Orange Trees. For one thing, it’s where you line up to buy tickets.

This tranquil oasis, with its fragrant blossoms and centuries of history, offers a contrast to the architectural wonders inside. And it’s not just orange trees — there are also olive trees, palms and cypresses.

In its long history, this courtyard been a place for reflection, prayer and community gatherings. And there was a section where Muslims would perform their ablutions, or ritual cleansings, before entering the mosque.

Visiting the Mezquita

Recognizing the Mezquita’s cultural and historical importance, UNESCO designated it a World Heritage Site in 1984. This status is a testament to the ongoing efforts to protect and preserve the architectural marvel, ensuring that future generations can continue to be inspired by its grandeur.

Pro tip: The early bird gets the arch.

We went early in the morning to see the Mezquita before mass was held. It’s free, so you don’t need to bother with tickets. (If you don’t go at this time, be sure to get your tickets as soon as possible. They cost 13 euros. I think it’s a good idea to book a day in advance if you have the time, but most travel sites say you don’t need to worry about it selling out. Call me paranoid.)

We figured the pre-mass time was a good way to escape the massive tour groups that would invade the space later in the day. To do so, you don’t go through the Patio de los Naranjos as you normally would. You enter through the Puerta de Santa Catalina. The one downside is that you don’t have a lot of time to explore. Get there right at 8:30, cuz security guards will kick you out around 9:20 so mass can begin.

This trick is considered the worst-kept secret in Córdoba, so keep in mind that word has gotten out. But it’s still supposed to be better than most other times. If you can’t make it early, or want more time, try booking the end of the day.

More Metamorphoses: Temple to Church to Mosque to Cathedral

Like the ceaselessly repurposed structures within its walls, the Mezquita represents the fluid nature of Spain’s cultural and religious history. As both mosque and church, this house of worship symbolizes Andalusia’s legacy as a place where Ancient Rome, Islam and Catholicism converge. For over 10 centuries, the awe-inspiring Mezquita has shifted shapes and uses but has endured. That’s typical of this wondrous part of Spain. –Wally