Once praised for its massive scale and beauty, El Badi Palace soon became a mere shell of its former grandeur. Only storks now call it home.

A ruined palace sits within the medina of Marrakech.

It must have once been quite a spectacle. El Badi Palace was commissioned by Ahmad al-Mansour, a Saadi sultan who ascended to power after his brother’s untimely death in 1578. Its financing came from ransoms paid by the Portuguese to release their prisoners who had been captured and enslaved following their defeat after the Battle of al-Qasr al-Quibir.

A ransom paid by Portugal financed the construction of El Badi Palace.

Al-Mansour and the Battle of Three Kings

The young and impetuous King Sebastian of Portugal wanted to reclaim coastal Morocco for his country and intended to convert the Muslim populace to Christianity. He combined forces with the deposed sultan al-Mutawakkil, who had his own aspirations to reclaim sovereignty.

When King Sebastian, al-Mutawakkil and their troops landed at Tangier, they were met by Sultan Abd al-Malik and his men. Within a mere six hours, the Muslim army easily forced the invading Christians to retreat to the port city of Larache — but while fleeing across the Wadi al-Makhazin at high tide, Sebastian and al-Mutawakkil drowned.

Exhausted from combat, Abd al-Malik fell ill and expired the following morning. In the end, all three died. For this reason, the event is also known as the Battle of Three Kings.

“Al-Mansour asked his court jester what he thought of his palace complex.

The jester replied, “It will make a magnificent ruin.” ”

Was this stork once a human being? Or is it off to deliver a baby?

Say Hi to the Storks: Visiting El Badi Palace

While staying in the Marrakech medina, we spent a day trying not to get lost and seeing the sights, including El Badi Palace.

Outside the site are shops. An open-air restaurant with charcoal braziers filled the air with oily black smoke. Enormous storks nests that could easily accommodate the three of us have taken up residence atop the remains of the rammed earth walls. The storks of Marrakech are considered to be holy animals. Even before the arrival of Islam, an old Berber belief held that storks were actually transformed humans. As a Westerner, I’m only familiar with storks delivering babies.

The silhouettes of storks seen at sunset. The birds find niches in the ruins of El Bahi Palace to build their nests.

Wally, our travel buddy Vanessa and I paid 10 Moraccan dirham (about $1) at the kiosk located outside the palace. We entered through a towering doorway and found ourselves enclosed in a massive bare-walled chamber open to a cloudless blue sky. These are the ruins of the Qubbat al-Khadra or Green Pavilion. The two-story pavilion most likely had a pyramidal roof of green terracotta tiles, a common material of the period.

El Badi means the Incomparable One.

Nothing Compares 2 U: The Incomparable Palace

The name of the palace derives from one of the 99 names of Allah given in the Qur’an, and translates to “the Incomparable One.” It served as the reception palace of al-Mansour, who spared no expense in building his lavish monument to the Saadian dynasty and its growing power.

While the palace was widely acknowledged in its time as a spectacular architectural achievement, it was plundered for its rich decorative materials only a century after its construction. However, you still get a clear sense of its monumental scale. The courtyard features four symmetrical sunken groves planted with lemon and orange trees surrounded by footpaths and separated by a large central basin, which was dry upon our visit but once provided irrigation for the orchards.

The sunken courtyards house small orchards of citrus trees.

It took nearly 16 years over the course of Sultan al-Mansour’s reign to complete, using materials imported from numerous countries, including onyx, Carrera marble from Italy, gold from Sudan, cedarwood and ivory. Walls and pathways were covered with multi-colored glazed zellij tiles arranged in geometric patterns.

The zellij tile floor is the one section of the palace with some color.

We met a fussy tomcat who at first craved our attention and then just as quickly grew fickle, batted a paw and hissed at us. (I think it was an angry jinn who became unhinged as we didn’t have any scraps of food to offer it.)

Sixteen-century Moroccan architecture during the Saadian period was heavily influenced by Andalusian decorative traditions, an Islamic architectural style that spanned across North Africa and Spain. El Badi’s layout follows a rectilinear grid similar to the Court of Myrtles at the Alhambra in Granada, Spain, but on a much larger scale.

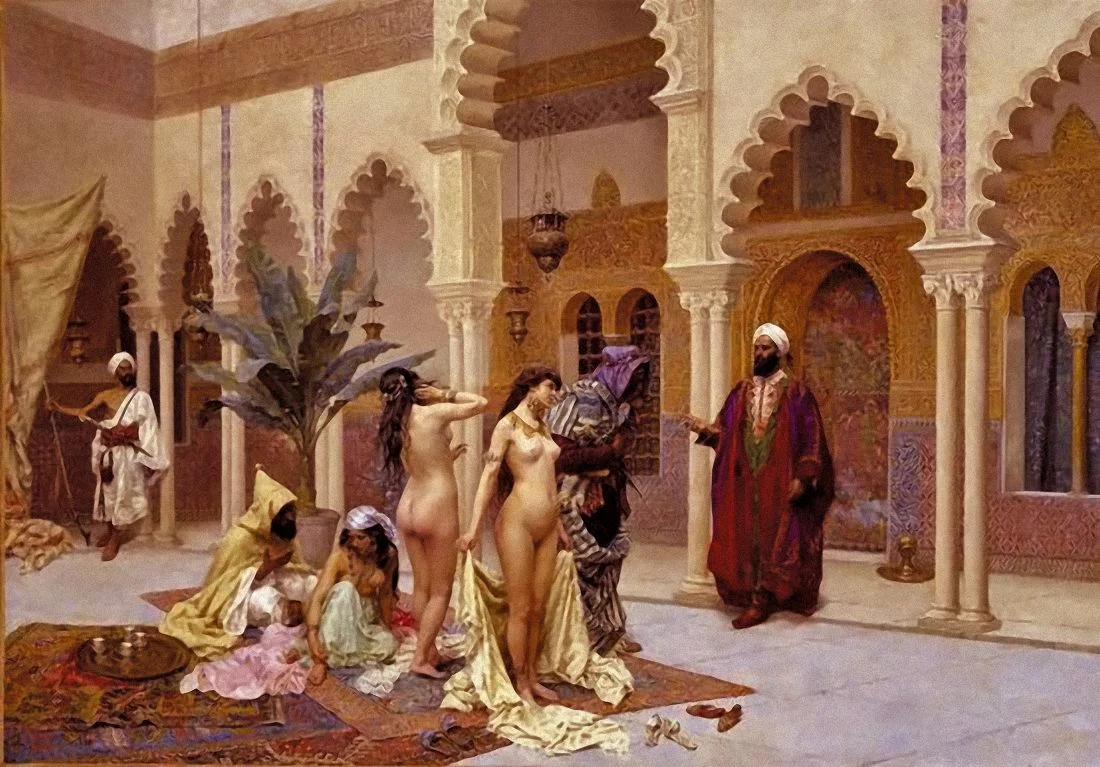

Foreign ambassadors of the time gushed about El Badi’s unparalleled beauty and grandiose domed pavilions: In addition to the Green Pavilion, there’s the Qubbat ad-Dahab (Golden Pavilion), the Qubbat az-Zujaj (Crystal Pavilion) and the Qubbat al-Khayzuran (Khayzuran Pavilion). According to a plaque outside the latter, Khayzuran comes from the Arabic name for wild myrtle and is believed to have been the harem’s quarters.

I’d suggest bringing bottled water and sunblock, as the site is mostly exposed. Although there isn’t a dress code, it’s respectful to stay modest wherever you go in Morocco. Wally and I both wore linen pants, and Vanessa covered up appropriately.

It’s too bad the grandeur of the palace didn’t last long. Moulay Ismail stripped El Badi and repurposed the materials to build a new residence in nearby Meknès.

El Badi’s Short-Lived Beauty

Less than a century after the construction of El Badi, the 17th-century Alaouite Sultan Moulay Ismail decided to move the capital from Marrakech to Meknès, and spent over 10 years systematically stripping El Badi of its riches to reuse for his palace in the new capital city.

This could explain why, as far as ruins go, El Badi might have once been astounding, but now it just doesn’t inspire much awe. That being said, according to local lore, al-Mansour asked his court jester, who was in attendance at the official opening, what he thought of his palace complex. The jester replied, “It will make a magnificent ruin.” And indeed it does. –Duke

If you have a few days in Marrakech, you should visit El Badi Palace. If time is limited, skip it and do the souk and Jardin Majorelle instead.

El Badi Palace

Ksibat Nhass

Marrakech 40000

Morocco