Europe’s oldest continuously used palace and UNESCO World Heritage Site is the best thing to see in Seville.

A palace like no other — the Real Alcázar of Sevilla dazzles with its stunning Mudéjar design with intricate stucco details.

After a quick, delicious breakfast at charming Filo, Wally and I made our way to Plaza del Triunfo (Triumph Square), the plaza where the Real Alcázar de Sevilla (Royal Palace of Seville) and its formidable main entrance, the Puerta de León (Lion Gate), stand. It’s just to the southeast of the Seville Cathedral.

Thanks to Wally’s planning, all we had to do was show up at our scheduled time and wait in the line on the left, which was designated for pre-purchased ticket holders. That being said, it was a bit confusing — we weren’t sure we were in the right line, and the tickets Wally had purchased looked different than other people’s. So there was some apprehension until they were scanned and we were able to enter the palace complex.

The monumental Puerta de León (Lion Gateway) serves as the main entrance to the Real Alcázar de Sevilla.

Puerta de León (Lion Gateway)

While we waited, I looked up at the tile panels set into the lintel above the gate. It depicted a peculiar, emaciated lion wearing a crown with its tongue lolling out of its mouth. It’s standing atop the flags of its defeated enemies, with a cross in its paw.

This passage was added by the Castilian monarch Pedro I (who reigned from 1350-1369) to provide direct access to his royal residence. The gate takes its name from the heraldic lion, a symbol of the Spanish crown’s power and protection. Although the defensive wall dates back to Almohad rule, the rampant lion was a more recent addition, created in 1892 at the Mensaque Rodríguez ceramic factory in Triana, the center of glazed-tile production in Seville.

A statue of the Virgin and Child located within the stone walls of the Lion Gateway en route to the Patio de la Montería (Courtyard of the Hunt)

Wally and I passed beneath the puerta, where an attendant checked our tickets. Just beyond was the expansive Patio de la Montería (Courtyard of the Hunt), the main courtyard of the Royal Alcázar of Seville, where Pedro I and his noblemen gathered before embarking on royal hunts.

Carlos Blanco’s portrait of Fernando VII, one of the many royals who once called the Alcázar home.

Casa de Contratación de Indias (House of Trade for the Americas)

We continued through the enclosed courtyard of the Patio del Cuarto Militar (Courtyard of the Military Quarter), which perfectly framed the blue sky above. From there we entered the Casa de Contratación de Indias (House of Trade for the Americas). The Renaissance-period addition was commissioned in 1503 by Isabella I of Castile and designed to regulate the flow of goods arriving from the New World, whose colonization had begun 11 years prior. Due to its location on the banks of the Guadalquivir River, Sevilla became an epicenter of commerce and trade, where ships set sail and returned to the port laden with goods from across the seas.

The Cuarto del Almirante (Admiral’s Quarters) is presided over by a large oil painting by Alfonso Grosso Sánchez depicting King Alfonso XIII and Queen Victoria Eugenia at the inauguration of the Ibero-American Exposition held in Seville in 1929.

Cuarto del Almirante (Admiral’s Room)

After passing through the main doorway, Wally and I entered the spacious Cuarto del Almirante (Admiral’s Room), whose walls have 19th and 20th century paintings of historic events, along with a collection of royal portraits. It was here that explorers and pilotos mayores (master navigators) such as Amerigo Vespucci, Ferdinand Magellan and Juan Sebastián Elcano signed their contracts and charted their voyages, while cartographers drew up detailed maps and navigational charts to assist them on their travels.

Among the traditional Spanish hand fans in the Sala de los Abanicos (Hall of Fans) are the Abanico Inglés (English Fan), made of mother-of-pearl and silk, handpainted with birds and flowers, and the Abanico Macao (Chinese Fan), a handpainted silk fan with tortoise-shell ribs depicting a traditional court scene from the province of Macau.

Sala de los Abanicos (Hall of Fans)

The following room was the Sala de los Abanicos (Hall of Fans), which held glass vitrines displaying a collection of antique fans amassed and donated to the Real Alcázar in 1997 by María Trueba Gómez. Among the beautiful and rare examples is a tortoiseshell and Chantilly lace fan, as well as a mother-of-pearl and silk fan commemorating the wedding between Alfonso XII of Spain and María Cristina Habsburg-Lorena of Austria.

The Sala de Audiencias (Chapterhouse) is where you’ll find the Virgen de los Navegantes (Virgin of the Navigators) altarpiece, the first religious artwork linked to the discovery and conquest of America.

Sala de Audiencias (Chapterhouse)

After the Sala de los Abanicos, we entered the square-shaped Sala de Audiencias (Chapterhouse). This room includes a stone bench where chapter members sat. In front of these seats is an altarpiece inspired by the discovery of the Americas.

The central panel was painted in 1535 by Alejo Fernández and is titled Virgen de los Navegantes (The Virgin of the Navigators). Fernández’s painting depicts the Virgin Mary hovering above a harbor, with her outstretched arms and billowing mantle sheltering notable navigators and monarchs, including Christopher Columbus, Amerigo Vespucci, Fernando II of Aragón and Carlos V, from the dangers of the sea.

Flanking the Virgin are four smaller panels with saints, from left to right and top to bottom: San Sebastiano (Saint Sebastian), shown with a sword, a bow and an arrow piercing his chest; Santiago Matamoros (Saint James the Moor-Slayer) riding a white horse; San Telmo (Saint Elmo), the patron saint of sailors, dressed as a Dominican and holding a ship in his hand; and San Juan Evangelista (Saint John the Evangelist) with his book, pen, scroll and eagle.

The entrance to the Cuarto Real (Upper Palace), which acts as a museum. For an additional fee, visitors can tour the royal residences.

Cuarto Real (Upper Palace)

Wally and I proceeded to ascend the staircase leading to the Cuarto Real (Upper Palace), where the private residences of the royal family are located. Throughout its long history, the palace has undergone numerous renovations and expansions by various kings, particularly during the 16th, 17th and 19th centuries.

Detail of a tarjetero, a large plate for holding social calling cards, designed by Manuel Arellano y Campos in 1894.

Since we didn’t purchase tickets (as admission to visit these is separate), we didn’t get to tour them, but we did wander through a small museum displaying ceramic objects from the collection of Vicente Carranza. The pieces are arranged chronologically, starting with Muslim and Mudéjar ceramics from the late 12th century, followed by Renaissance ceramics, and ending with Baroque ceramics from the 18th century.

A tranquil haven within the Real Alcázar, the Patio de Levíes captivates with its symmetry and the quiet beauty of its reflecting pool.

Patio de Levíes (Courtyard of the Levis)

Back outside, Wally and I found ourselves in the tranquil Patio de Levíes (Courtyard of the Levis), which likely gets its name from the slender columns supporting four semicircular arches that were taken from the residence of Samuel Leví, the treasurer of King Pedro I.

The carved fountain spout, known as “grotesque,” in the Patio de Levíes combines artistry and utility.

Set into the wall on the left side of the patio is a Baroque-style ceramic tile altarpiece depicting the Immaculate Conception. At the center of the courtyard is a narrow reflecting pool with a gargoyle-faced fountain, flanked by white marble columns of the Ionic order.

The Romero Murube Courtyard, named after a famed Sevillian poet

Patio de Romero Murube (Romero Murube Courtyard)

Between the Patio de Levíes and Jardín del Príncipe (Garden of the Prince) is the Patio de Romero Murube (Romero Murube Courtyard), whose name refers to Joaquín Romero Murube, a poet and the curator of the Real Alcázar from 1934 to 1969.

Wally takes a break on a bench in the courtyard.

The courtyard’s design reflects the style of 19th century Sevillian domestic architecture, with a pair of flowerbeds on either side and a tile-covered bench framed by pink marble columns.

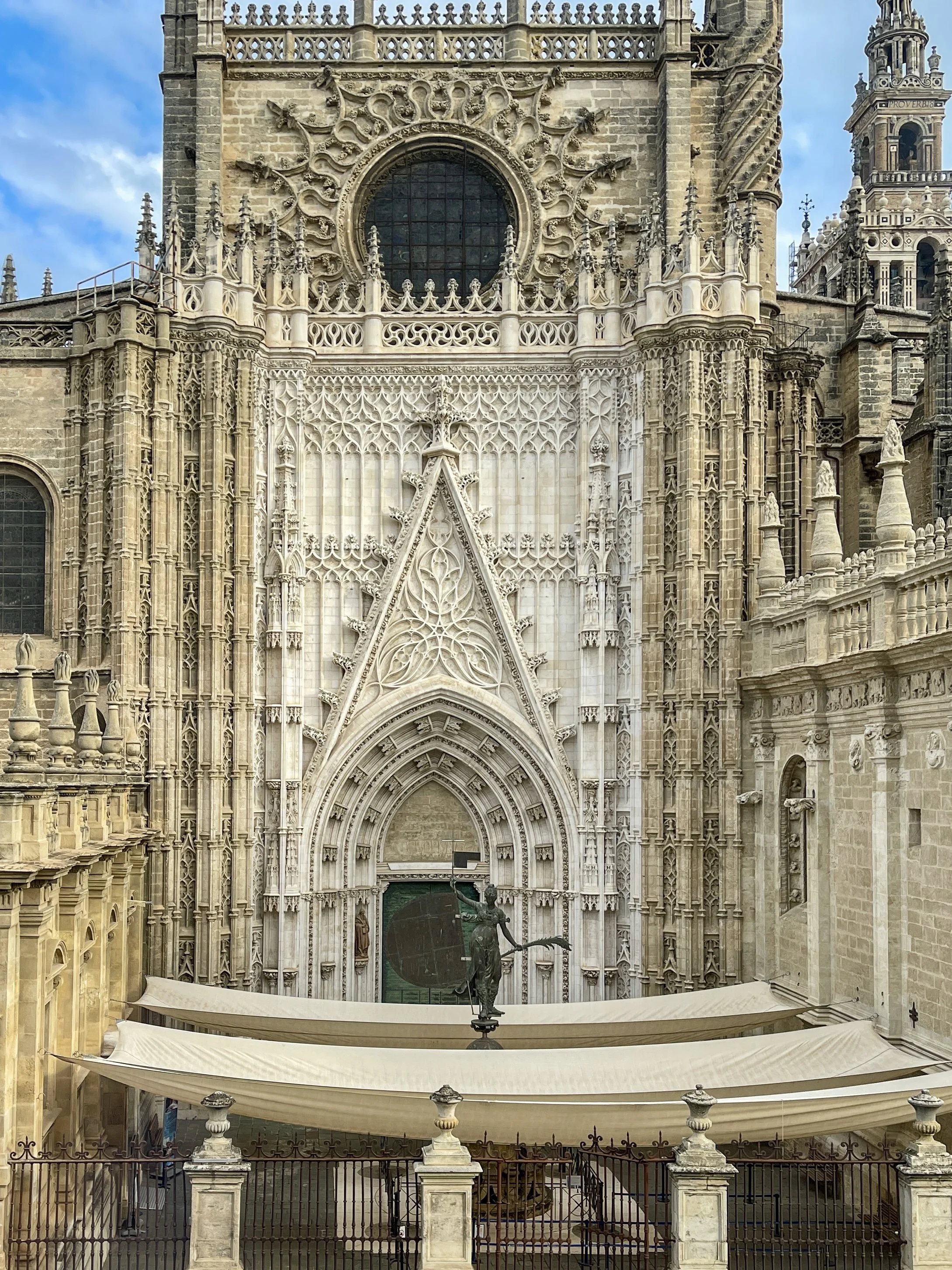

The entrance to the palace, crafted by artisans from Granada, Toledo and Seville, is considered a masterpiece of Mudéjar architechture.

Palacio del Rey Don Pedro I (Palace of King Don Pedro I)

Standing opposite the Puerta de Leon is the Palacio del Rey Don Pedro I (Palace of King Don Pedro I), a majestic 14th century masterpiece of Mudéjar architecture.

The young prince came of age during a period of religious tolerance toward Muslims and Jews and a fondness for Mudéjar architecture, which blends Muslim aesthetics with local traditions. At just 15, Pedro became the final ruler of the House of Ivrea after his father, Alfonso XI, fell victim to the bubonic plague.

Pedro’s reign was a study in contrasts. To some, he was el Cruel (the Cruel), while to others, he was el Justiceiro (the Just) — depending on which side of his sword you stood. The only solution the young king ever seemed to find for resolving political conflict was to eliminate anyone who posed a threat. One of his first acts was to target his father’s mistress, Leonor de Guzmán. Shortly after taking the throne, he had her imprisoned, and following his mother’s orders, she was executed by Pedro’s chancellor, Juan Alfonso.

Pedro ruled alongside his mistress, María de Padilla, and used his alliance with the exiled Nasrid sultan, Muhammad V of Granada, to bring in some of the most skilled Muslim builders and craftsmen from Granada, Toledo and Seville. Between 1356 and 1366, these craftsmen built his royal residence within the walls of the Alcázar in the Mudéjar style, which is why his palace bears such a strong resemblance to the Nasrid Palaces at the Alhambra.

The intricate grillwork adorning this doorway exemplifies the Mudéjar style’s mastery of geometric patterns.

Originally, the term mudejár, derived from the Arabic mudajjan, meaning “domesticated” or “tamed,” was a derogatory label given to Muslims who chose to remain in al-Andalus under Christian rule after the Reconquista. Yet, as time passed, it came to represent something far more enduring — the synthesis of Islamic forms and decorative elements within Christian architecture. This distinctive style of art and architecture includes features like horseshoe arches, carved stucco, geometric tile compositions, muqarnas (stepped, stalactite-like vaulted ceilings) and carved wood.

However, Pedro didn’t get to enjoy his palace for long. On March 23, 1369, just three years after the building’s completion, Pedro was assassinated at the age of 34 by his half-brother, Enrique. This treacherous act propelled Enrique to the throne as Enrique III, marking the beginning of the new Trastámara dynasty.

The window grille showcases elegant geometric patterns and stylized arches.

The palace’s main entrance is framed by two blind multifoil arches embellished with panels featuring symmetrical vegetal and geometric designs known as sebka.

Above, the second-story gallery has three multifoil window arches. A horizontal blue and white frieze bears the Kufic inscription written forward and in mirror image: “There is no victor but Allah.” Framing this is a secondary band dedicated to Pedro I in Latin: “El muy alto y muy noble y muy poderoso y muy conquistador don Pedro, por la gracia de Dios Rey de Castilla y de León, mandó hacer estos Alcázares y estos Palacios y estas portadas que fue hecho en la era de mil cuatrocientos y dos.” This translates to, “The highest, noblest and most powerful conqueror, Don Pedro, by God’s grace the King of Castile and León, ordered the construction of these Alcázares, and these palaces, and these façades, completed in the year 1402.”

We stepped through the palace’s main door and found ourselves in a spacious two-story vestibule. In keeping with Islamic tradition, arches divided the reception hall into two smaller rooms with a broken axis of sharp right-angle turns, an ingenious architectural device designed to maintain the privacy of interior spaces. To the left was the Patio de las Doncellas (Courtyard of the Maidens), and to the right stretched the passageway leading to the Patio de las Muñecas (Courtyard of the Dolls).

Located in the palace’s private area, reserved for the enjoyment of the monarch and his family, the Patio de las Muñecas (Courtyard of the Dolls) includes elegant marble columns, sourced from the caliphal palace city of Madinat al-Zahra.

Patio de las Muñecas (Courtyard of the Dolls)

The intimate courtyard is one of the palace’s private spaces and owes its name to the small doll-like faces that decorate the bases of the cusped arches surrounding the patio. According to tradition, whoever finds these attracts good luck, and eligible girls are believed to find husbands. Like Córdoba’s magnificent Mezquita Mosque, the columns of black, white and pink marble that support the arches came from the former palace of Madinat al-Zahra.

Touring the Alcázar is a contrast of admiring serene beauty while surrounded by throngs of fellow tourists.

The two upper floors were added during the 19th century, and the domestic rooms were completely remodeled during the reign of the Catholic Monarchs. However, the showstopper here is the elegant glass skylight that turns this courtyard into a solarium.

The cupola roof of the Hall of Ambassadors is visible from the Patio de las Doncellas (Courtyard of the Maidens).

Patio de las Doncellas (Courtyard of the Maidens)

At the heart of the palace is the Patio de las Doncellas, the main courtyard. It’s encircled by a gallery of delicate, lace-like multifoil arches, each supported by pairs of double columns brought from Genoa during the Renaissance to replace the original brick pillars.

The Patio de las Doncellas’ lower level features an arcade of polylobed arches reflecting the Mudéjar style, while the upper gallery incorporates semicircular arches influenced by the principles of the Italian Renaissance.

In contrast, the upper gallery, separated by a marble balustrade and semicircular arches, was added between 1540 and 1572 during the reign of Carlos V and reflects the Renaissance style. Despite their stylistic differences, these elements blend harmoniously, creating a space that is both cohesive and visually arresting.

In the center of the courtyard is a rectangular pool flanked by sunken gardens with orange trees.

The scallop motif, symbolizing the authority of the Catholic monarchy, seamlessly integrates with Mudéjar designs, highlighting the interplay of cultures and faiths in the Real Alcázar.

The name of the courtyard is tied to a controversial legend: It references a supposed annual tribute of 100 virgin maidens that the Christian kingdom of Asturias was required to send to the emirate of Córdoba. Each year, the Christian rulers allegedly selected the maidens — young women from noble and common families alike — to be sent to Córdoba. Many were believed to have been enslaved, serving as concubines or laborers in the palaces of the emirate.

While there’s no historical evidence to confirm that such a tribute actually occurred, the story persisted in Christian retellings to underscore the perceived cruelty of Muslim rule and bolster the Christian narrative of righteous resistance.

The sunken garden in the Courtyard of the Maidens is a result of a 20th century restoration of the original Islamic-era design, rediscovered through archaeological evidence and reinstated after centuries of Renaissance alterations.

The courtyard has also made its mark on popular culture, appearing as a striking backdrop in Ridley Scott’s epic film Kingdom of Heaven and as a setting in the popular HBO fantasy series Game of Thrones, where Ellaria Sand kneels before Prince Doran.

The alcove used as a bedchamber by the king during the summer months is topped by a pointed barrel vault, designed to keep the space cool.

Alcoba Real (Royal Chamber)

The Alcoba Real (Royal Chamber) is another one of the private palace rooms and is accessible from the ground floor gallery of the Patio de las Doncellas. Its interior is divided into an antechamber and a bedroom with alcoves on the sides. Its lower walls are covered with colorful ceramic tile compositions in turquoise, royal blue and orange.

Once used by Pedro I as his throne room, the Salón de Embajadores (Hall of Ambassadors) stands as the most magnificent room in the palace. Its opulent design perfectly embodies its purpose as a symbol of regal authority and grandeur.

Salón de Embajadores (Hall of Ambassadors)

One of the most spectacular rooms in the Real Alcázar is the Salón de Embajadores (Hall of Ambassadors). Originally, it served as the throne room for Pedro I, where he received dignitaries and other important visitors.

Beneath the shimmering, gilt dome of the opulent Hall of Ambassadors is a frieze depicting castles and lions, and below that Gothic niches containing portraits of Spanish kings.

The walls of the room are covered with intricate tile and finely carved stucco work and follow the architectural scheme of a qubba — a structure in Islamic architecture, often as a mausoleum or shrine — which features a cubic floor plan with a spherical dome above it. The square base represents the earth, while the domed ceiling symbolizes the vastness of the universe above.

The ceiling of the Cuarto de Príncipe (Prince’s Suite) was created during the reign of Charles V in 1543 and is adorned with golden honeycomb-like mocarabes.

Cuarto de Príncipe (Prince’s Suite)

You’ll find the Cuarto de Príncipe (Prince’s Suite), through the north gallery of the Patio de las Muñecas. This historic space includes a central hall with two smaller alcove rooms on each side. The room is named after Juan de Trastámara, the only son of Fernando II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile. He was believed to have been born here in 1478.

Look up, and you’ll find a ceiling decorated with the heraldic symbols of the Catholic Monarchs, with plaster arches dividing the room into three sections.

Islamic design, as seen on the lower walls of the Prince’s Suite, avoids depictions of people or animals, reflecting a focus on abstract patterns and geometry as a way to honor the divine without creating so-called idolatrous imagery.

We exited the Palacio del Rey Don Pedro I through a set of wrought iron and glass doors into the back gardens of the Real Alcázar — a serene oasis and the perfect respite after the dazzling beauty of the Mudéjar palace, which left us awestruck with its intricate details and overwhelming splendor. –Duke