From its fascinating history to its stunning Baroque architecture, the Templo de Santo Domingo de Guzmán Church is a must-see attraction in Oaxaca.

Like most churches in Mexico, the Templo de Santo Domingo de Guzmán in Oaxaca has got history, style, beauty, drama and a whole lot of swag.

Holy History: The Evolution of Templo de Santo Domingo de Guzmán Church

Construction of the church began in 1572 and was completed over three decades later, in 1608. The building was designed by Fray Francisco de la Maza, a Spanish architect who was a member of the Dominican Order.

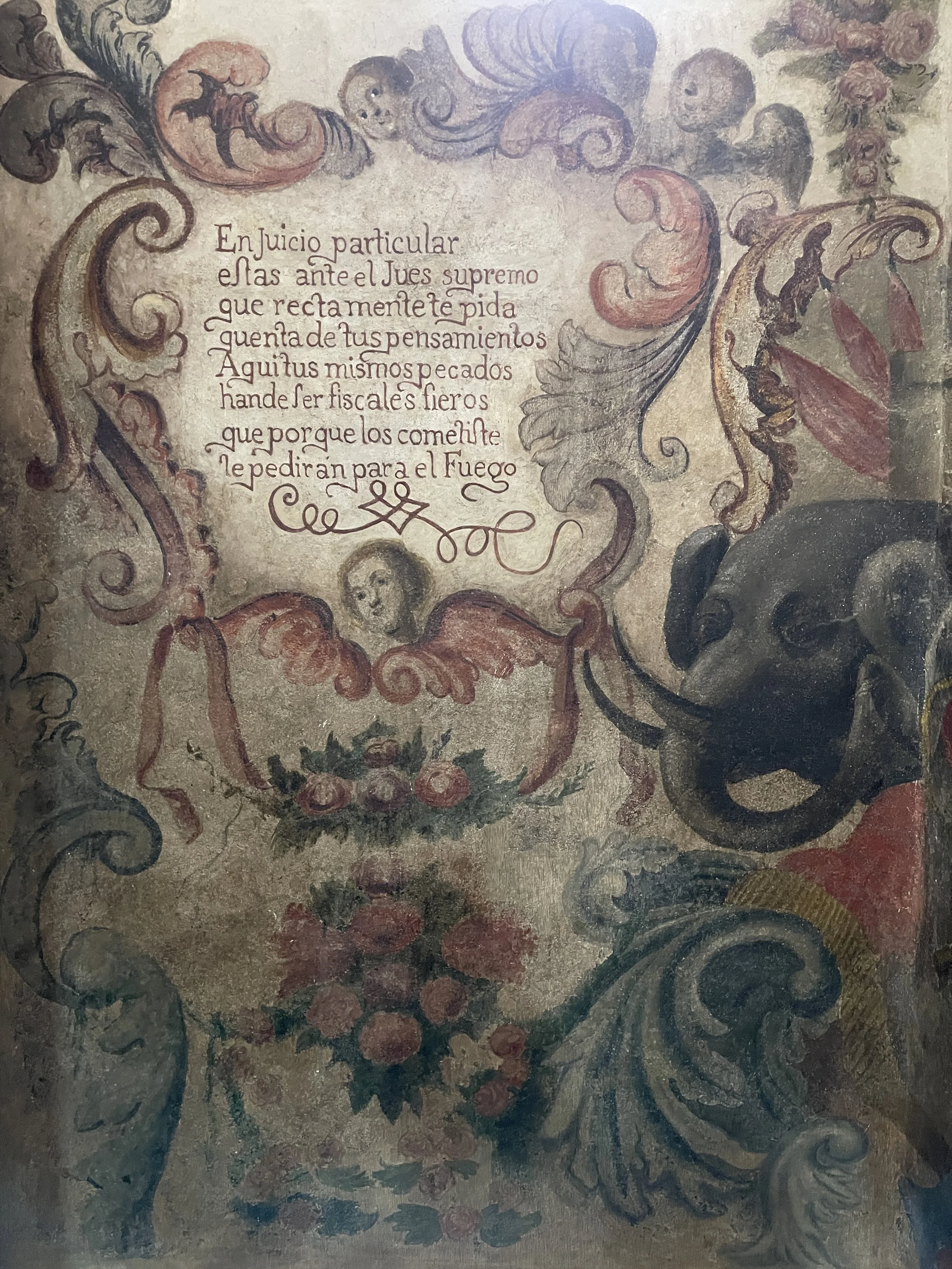

“Inside the church, visitors are treated to a riot of color and decoration.

The walls and ceilings are covered in frescoes of the life of Christ and the history of the Dominican Order.”

Also par for the course: The church was built on the site of an existing temple that was destroyed during the Spanish conquest of the region. The original temple was dedicated to Cosijoeza, a Zapotec ruler from the late 15th century. He was a skilled warrior who fought against the Aztecs and other neighboring tribes to defend his people’s land and culture. He acted as shaman and healer as well, and was said to have possessed great spiritual power.

According to legend, Cosijoeza ascended to the heavens after his death, becoming a god who watches over the Zapotec people and protects them from harm.

During the colonial period, the Templo de Santo Domingo de Guzmán was built as a symbol of the power and wealth of the Catholic Church and the Spanish colonial authorities. The church was lavishly decorated with gold leaf, marble and other precious materials, and it served as a center of religious and cultural life in Oaxaca.

In the 19th century, the church played an important role in the Mexican War of Independence, serving as barracks for both royalist and insurgent forces at different times. After Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821, the church continued to be the spiritual heart of Oaxaca, and it was eventually designated as a national monument in 1935.

Today, the Templo de Santo Domingo de Guzmán is one of the most visited tourist attractions in town, attracting thousands of visitors each year.

What’s in a Name? The Legacy of Santo Domingo de Guzmán

Saint Domingo de Guzmán was a Spanish priest who lived in the 12th and 13th centuries. He founded the Order of Preachers, also known as the Dominican Order, which was dedicated to preaching the gospel and combating heresy. Saint Domingo was known for his zeal and devotion to spreading the teachings of the Church.

There was no dramatic act of martyrdom for Santo Domingo, though: He died of a fever in Bologna, Italy in 1221, and was canonized by the Catholic Church in 1234.

Divine Design: The Intricate Baroque Style of Templo de Santo Domingo de Guzmán Church

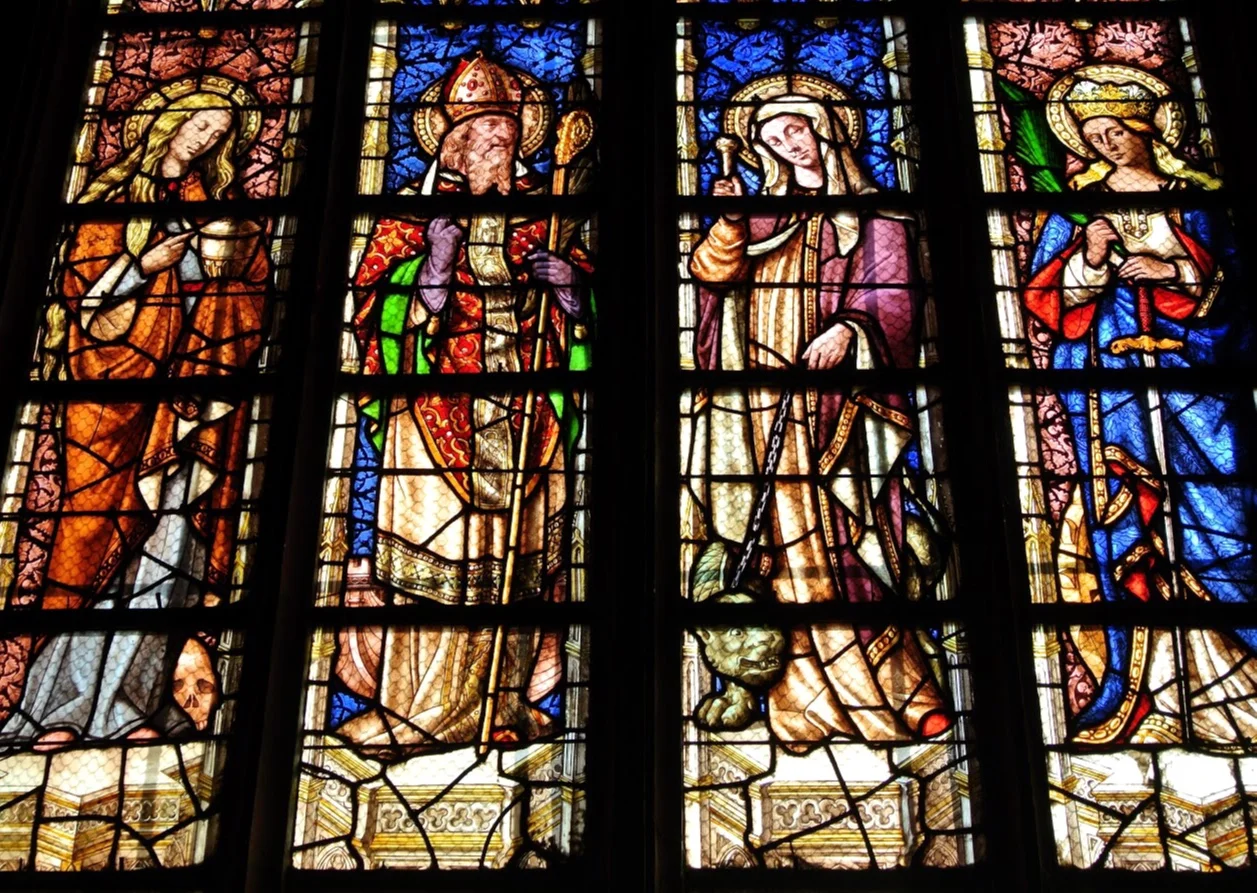

Mexican churches tend not to be subtle. The Templo de Santo Domingo de Guzmán Church is a masterclass in Baroque architecture, a visual feast, with intricate details both inside and out. The exterior is adorned with elaborate carvings and statues, featuring saints, angels and other religious figures. The façade is made of Cantera verde, the local green volcanic stone, which glows a lovely yellow in the sunshine. Three domes top the templo — two blue and white checkered ones atop the entrance and a larger red tile one to the side.

When we saw this woman posing in front of the church, we had to get in on the action.

Inside the church, visitors are treated to a riot of color and decoration. The walls and ceilings are covered in frescoes and murals featuring scenes from the life of Christ and the history of the Dominican Order.

The altarpiece, which was carved from a single piece of cedar, is gilded with gold leaf and decorated with intricate carvings of saints, cherubs and other religious motifs.

To the right of the nave is the Capilla del Rosario, or Chapel of the Rosary, with its own stunning altarpiece.

There’s a museum attached to the church. Hopefully it’s open when you visit!

Sacred Treasures: The Artifacts and Exhibits of the Templo de Santo Domingo de Guzmán Church Museum

There’s a museum in the massive edifice as well, to the left of the main church entrance. Unfortunately it was closed when we visited, but it holds an impressive (and surprisingly diverse) collection of religious art, including paintings, sculptures and tapestries, housed in the former monastery of the Dominican Order.

One of the highlights of the museum is the collection of pre-Hispanic artifacts, including pottery, sculptures, and other objects from the Zapotec and Mixtec cultures. You can also see a wide range of religious art from the colonial period. There’s even a collection of contemporary art, with rotating exhibits featuring the work of local and international artists, as well vintage photographs and cameras.

As our friend Kevin, who lives in town, says, “There’s a parade or festival every day in Oaxaca.” This indigenous dance troupe performed in the plaza in front of Santo Domingo de Guzmán.

When you’re in Oaxaca de Juárez, you’ll inevitably find yourself passing by the massive Templo de Santo Domingo de Guzmán. Be sure to stop inside and admire the gilded glory — and plan a tour of the Oaxaca Botanical Garden (Jardín Etnobotánico de Oaxaca) on the grounds of the former Dominican monastery behind the church. –Wally

Templo de Santo Domingo de Guzmán

Calle Macedonio Alcalá s/n

Centro

68000 Oaxaca de Juárez

Oaxaca

Mexico