The surprisingly popular Museo de las Momias is filled with naturally preserved corpses, dried out and twisted into gruesome positions. Their wide-open mouths are enough to make visitors scream.

There’s a museum filled with naturally preserved corpses in Guanajuato, Mexico — and it’s a popular attraction with locals and warped tourists alike.

While researching a day trip from San Miguel de Allende, Duke said, “There’s a mummy museum in Guanajuato—”

“Say no more!” I interrupted him. “I’m sold.”

It’s just the kind of perverse spectacle that made us name our site The Not So Innocents Abroad.

“This woman had wakened under the earth. She had torn, shrieked, clubbed at the box-lid with fists, died of suffocation, in this attitude, hands flung over her gaping face, horror-eyed, hair wild.”

And we’re not the only ones into this type of gruesome excursion. The parking lot was full, and there was a line to get into the museum. All told, we had to wait about 20 minutes to purchase tickets.

“The mummies of Guanajuato bring the biggest economic income to the municipality after property tax,” Mexican anthropologist Juan Manuel Argüelles San Millán told National Geographic. “Their importance is hard to overstate.”

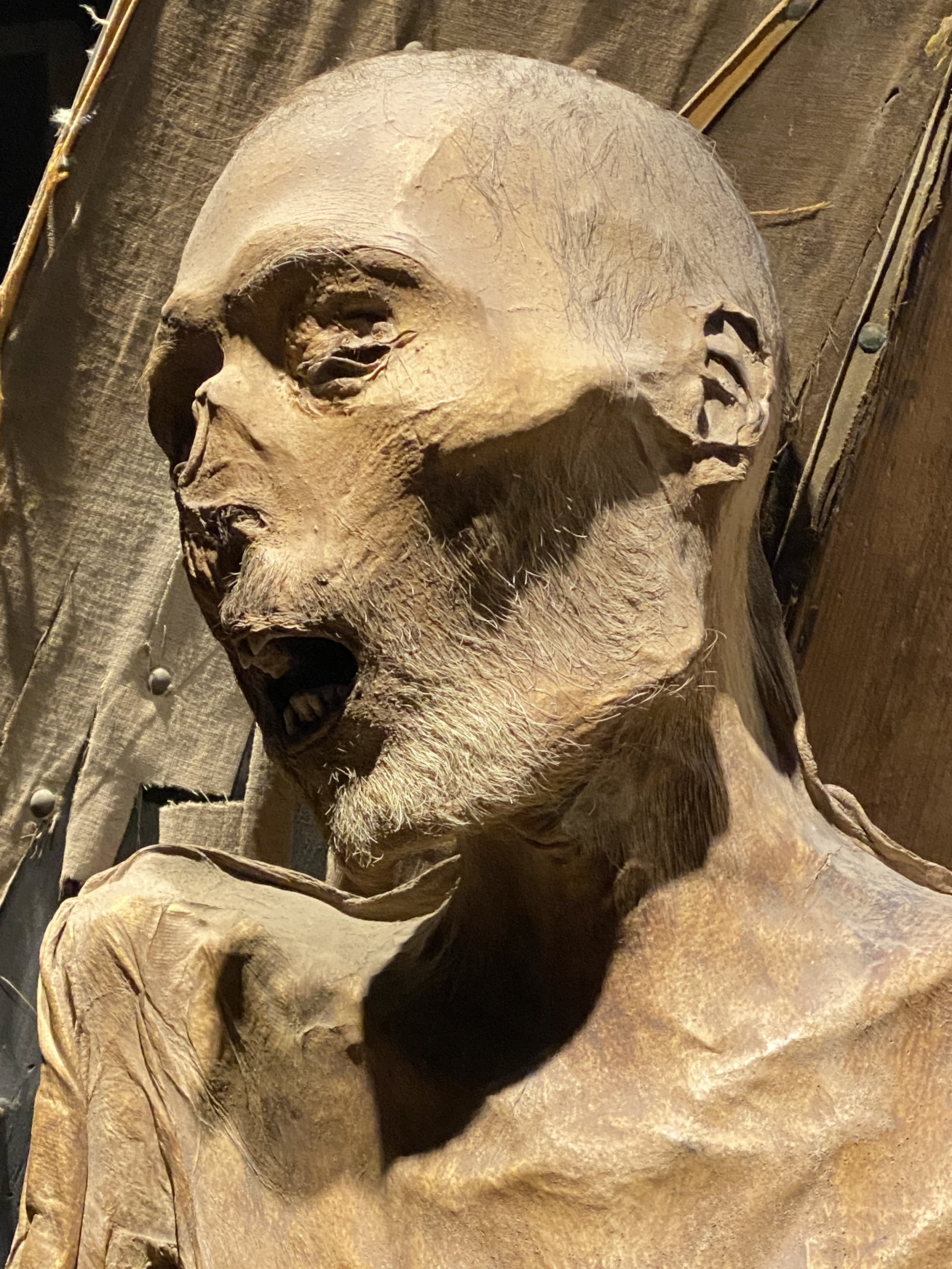

Meet the oldest mummy at the museum: Dr. Remigio Leroy, buried in 1860 and exhumed five years later.

Many of the mummies still have their hair and teeth — and dried sacs where their eyes have oozed out.

Our tour guide spoke in Spanish — most of the visitors were locals as opposed to fellow gringos. Our Spanish is nowhere near good enough to follow what he was saying, but we trailed after the group, snapping photo after photo.

The mummies are pale and desiccated, twisted into horrific poses, their arms crossed over their chest or fingers bent at unnatural angles. The dried skin has flaked off in many areas, looking like a wasp nest, though on a few the skin is pulled taut and smooth. On some, the eyes look as if they’ve oozed out of their sockets to become dried sacs. Quite a few still have their teeth; you’ll see tongues protruding from others. Some still wear dusty clothes, pulled from their graves before the fabric had time to rot away.

Many still have their hair, wild manes or neat braids. We passed a mummy that had a large patch of gray pubes, which made us groan and then giggle.

This mummy still sports a patch of gray pubes.

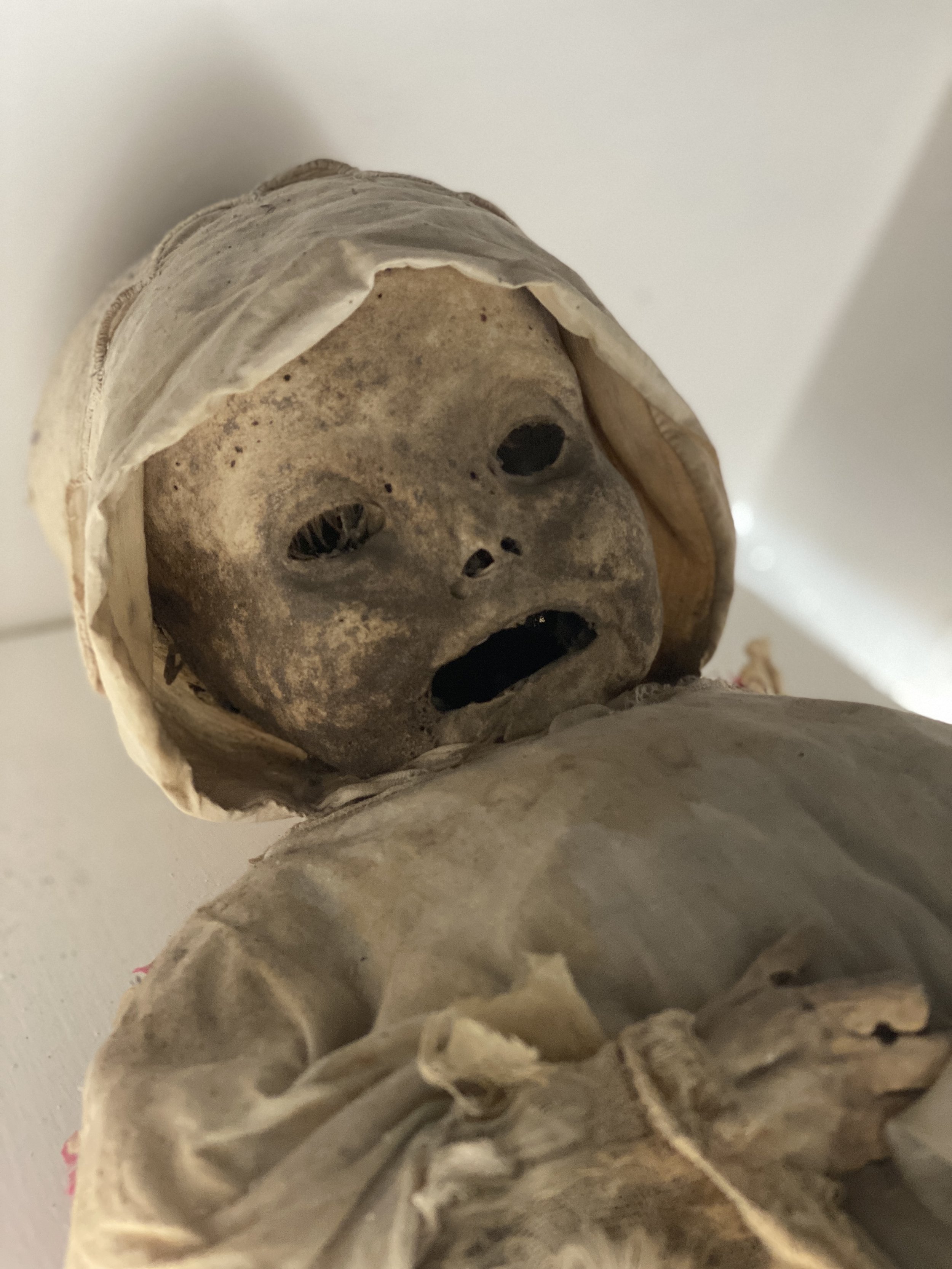

One somber section is devoted to babies, eerie infants dressed in gowns and caps, looking like dreadful dolls.

But what you notice most are the mouths. They’re open in what appears to be an eternal scream. They’re screaming, as if they knew what their ignominious fate would be.

So, how did the mummies end up here?

If you’re buried in Guanajuato and no one pays your burial tax…you could end up a mummy at the museum!

Exhumed and Exploited

Unlike a cemetery in the United States, where you buy a plot of land for perpetuity, the gravesites in the silver mining town of Guanajuato had a burial tax. If a family didn’t pay up, the corpse had to vacate the premises to make way for a paying customer.

The bodies at Santa Paula cemetery were moved to an underground ossuary — what happens to be the current site of the Museum of the Mummies.

Check out those cheekbones! This is considered to be the best-preserved mummy at the museum.

Those commissioned with the gruesome task of removing the corpses were shocked to discover that many were well preserved. Turns out that the deep crypts, devoid of humidity and oxygen, provided the ideal conditions to prevent decomposition. The bodies had dried out naturally, transforming into what are now known as the mummies of Guanajuato.

Gravediggers lined up the mummies and charged the public a few pesos to see them. Early viewers would break bits off of the mummies or nabbed name tags as souvenirs.

The macabre practice continued for 90 years, until 1958. Ten years later, the city opened el Museo de las Momias de Guanajuato, and 59 of the original 111 mummies are on display.

And so the tradition continues — though the museum now charges 85 pesos (less than $5). We sprang for the additional section, which turned out to be a kitschy collection of spooky spectacles in the vein of Ripley’s Believe It or Not!

One of the dioramas in the bonus room at the end.

Thought to be Asian, this mummy is referred to as the China Girl — and is the only one with its original coffin, despite being one of the oldest specimens in the collection.

Mummies Dearest

The first of the mummies dates back to 1865 and is that of a French doctor, Remigio Leroy. As an immigrant, he had no one to keep up his burial tax.

One unfortunate soul, Ignacia Aguilar, had a medical condition that greatly slowed her heart, and her family rushed to bury her (not unusual in warm climates). Ignacia was eventually unearthed, her mummy lying face-down — and the ghastly truth was discovered: Due to injuries on her forehead and the position of her arms, she’s believed to have been buried alive.

The corpse on the left is believed to have been buried alive, while the guy in the middle drowned.

And, alongside its mother, there’s a 24-week-old fetus, believed to be the youngest mummy in existence.

Analysis of the mummy showed that this woman was 40 years old and malnourished when she died while pregnant. Her fetus is thought to be that of the youngest mummy in existence.

Death on Display

The museum may be popular, but it also comes with its share of controversy. Aside from the questionable ethics of showcasing the forgotten dead in a freakshow of sorts, some scientists say that storing the mummies upright, as many are displayed, hampers preservation.

But this display of death is just part of the culture.

“For Mexicans, this isn’t bizarre or weird,” local guide Dante Rodriguez Zavala told Nat Geo. “We have a comfort level with death — we take food to our dead loved ones on Day of the Dead and invite mariachis into the cemetery.”

One of the scariest of the mummies

Pretending to be a mummy at the end

But for some, like writer Ray Bradbury, the experience is haunting. Bradbury, traumatized by his viewing of the mummies in 1945, wrote a fantastic, creepy short story about them called “The Next in Line.” It’s in his collection The October Country and will stick with you long after you finish reading it. The tale is the perfect companion piece to a visit to the Museum of the Mummies.

Much better than the schlocky horror flick Las Momias de Guanajuato (The Mummies of Guanajuato). This movie from 1972 is part of the luchador genre, starring three wrestlers from the time — Blue Demon, Mil Máscaras and Santo, the Silver Masked Man — saving the town from a resurrected sorcerer (and fellow wrestler) named Satan and his army of the undead. –Wally

Museum of the Mummies of Guanajuato

Explanada del Panteón Municipal

Centro

36000 Guanajuato

Guanajuato

Mexico