A virtual tour of the Masculin/Masculin exhibit at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, including works by Egon Schiele, Kehinde Wiley, Gustave Caillebotte and Pierre et Giles.

Le Berger Paris (The Shepherd Paris) by Jean-Baptiste Frédéric Desmarais, 1787

The perfection of the male figure was first seen through the lens of the Ancient Greeks. Their idealized depictions celebrated the male body as a reflection of heroic and athletic beauty. The few female sculptures that existed during this period were clothed and chaste in comparison.

At some point the male nude fell out of favor, and the female nude became the central subject of objectification. Historically speaking, the typical viewer of artwork was male, and this display of the female physique for pleasure turned the female nude into an accepted object of male desire.

Imagine if you will then, how excited Wally and I were in Paris in the fall of 2013. We had decided to visit the Musée d’Orsay, and saw that its featured exhibit was Masculin/Masculin: L’homme nu dans l’art de 1800 à nos jours (The Male Nude in Art From 1800 to Today). The exhibition ran from September 24, 2013 to January 2, 2014.

We arrived with Wally’s parents, Dave and Shirley, in tow. When we mentioned that we were excited to see a special exhibit all about the male nude, the Shirl replied, “I don’t need to see that.” Her loss! Though we can’t say we weren’t a bit relieved; seeing galleries full of nude men with your parents could get a little awkward.

Mercure (Mercury) by Pierre et Gilles, 2001

Nude Male Art Galleries Galore!

Inside, a larger-than-life banner featured a stylized work of French art photography duo Pierre et Gilles titled Mercure (Mercury), the heroic winged messenger and trickster deity of Roman mythology.

Please note that, as you can imagine from the title, this post includes images of male nudity.

Faune endormi (Sleeping Faun), a copy of the Barberini Faun, by Edmé Bouchardon, 1726

The Ideal Man

The exhibition is arranged thematically and began by introducing us to “L’Idéal classique, the Classic Ideal.” This concept has existed since the Ancient Greeks chiseled away at marble to depict perfectly sculpted male bodies (pun intended). In my humble opinion, though, these were rarely erotic — sure, they had rockin’ bods, but the statues’ minuscule, flaccid genitalia unappealingly evoke wilted zucchini blossoms.

One such exception was the life-size copy of the Barberini Faun by Edmé Bouchardon on loan from the Louvre. I can clearly remember seeing an image of the Barberini Faun projected onto a screen in my college art history class in its erotic, spread-eagled glory. The figure is a satyr, or faun — usually depicted as a creature half-man, half-goat but in this case referencing a follower of Dyionysus, the god of pleasure and wine.

Seeing the sculpture in person felt voyeuristic — the viewer is allowed to gaze at something forbidden: a man sleeping, or perhaps passed out from all that wine. The nude form is lounging back, with his legs splayed, giving everyone a view of the goods.

Académie d’homme dit Patrocle (Academy of a Man, Called Patroclus) by Jacques-Louis David, 1780

One of the first works of art we viewed was Académie d’homme dit Patrocle (Academy of a Man, Called Patroclus) by Jacques-Louis David, from 1780.

Patroclus was a character from Homer’s Iliad who died fighting the Trojans. The painting was produced by David during his stay in Italy as a Prix de Rome laureate. Turned away from the viewer, the figure's accentuated muscles reminded me a bit of Michelangelo's studies for the Libyan Sibyl, Phemonoe, the finished result of which adorns the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in Rome.

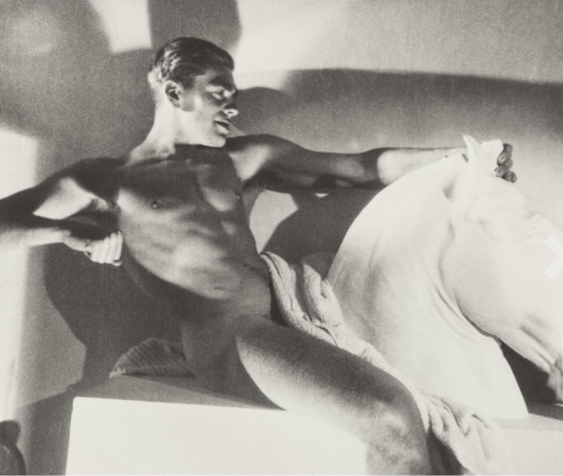

Horst in the Pose of an Ancient Greek Horseman by George Hoyningen-Huene, 1932

Gods and Heroes

The second theme, “Le Nu héroïque, the Heroic Nude,” also dates back to the Ancient Greeks. It was assumed that a hero had little need for armor, and that the strength of his body was the measure of his worth.

David by Antonin Mercié, 1892

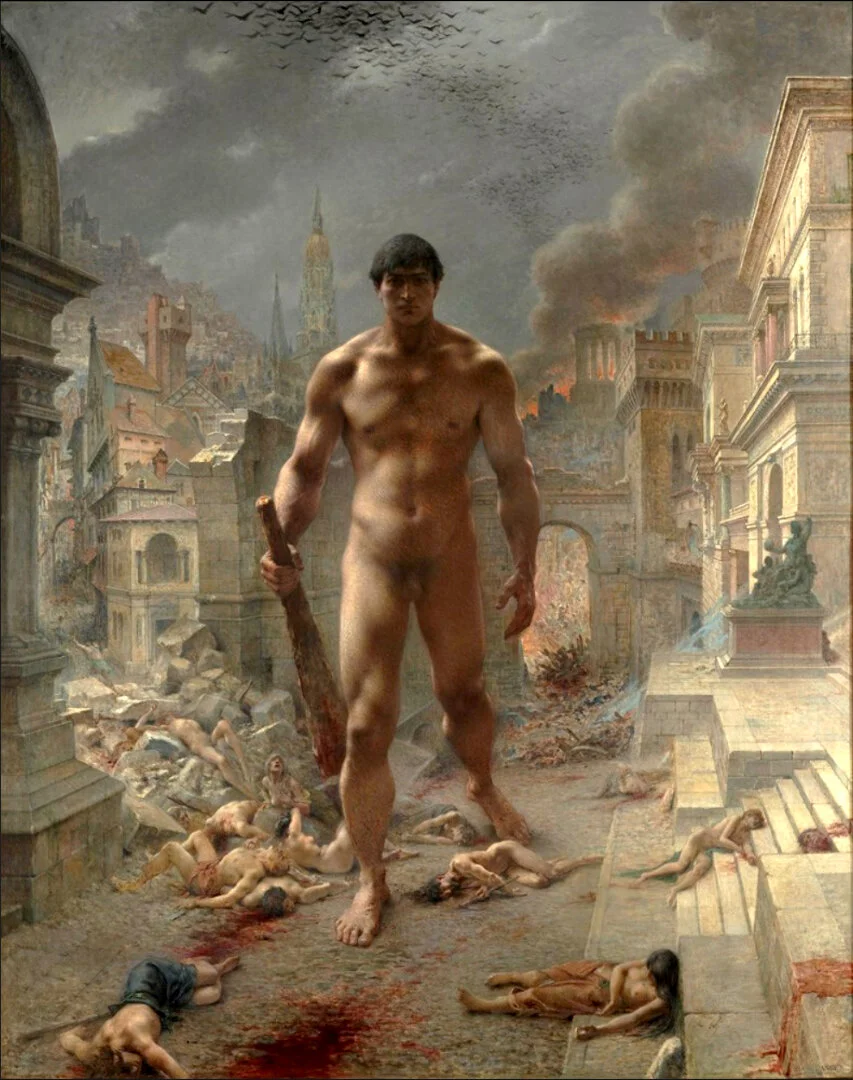

Fléau! (Scourge!) by Henri-Camille Danger, 1901

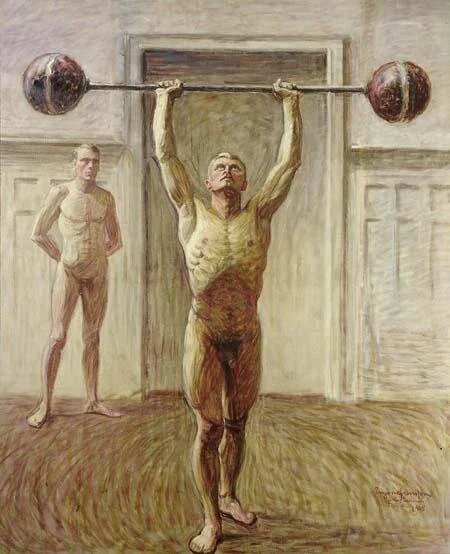

Pushing Weights With Two Arms -2 by Eugène Fredrik Jansson, 1913

A noteworthy inclusion in this gallery was Pushing Weights with Two Arms -2 by Eugène Fredrik Jansson, a Swedish artist. He began his career painting atmospheric landscapes and cityscapes rendered in shades of blue, but in later years turned his focus to painting male nudes. Jansson became a swimmer and winter bather to combat the chronic health issues he’d suffered since childhood. He often visited Stockholm’s Flottans Badhus, the Navy Bathhouse, where he met sailors who served as the models for his paintings.

Pushing Weights was a series of paintings by Jansson. In this particular one, a naked athlete stands near a doorway, his gaze fixed on a man, possibly Knut Nyman, Jansson’s “close companion,” lifting a barbell above his head.

Based upon the homoerotic subtext, it’s possible that Jansson was a closeted homosexual and that the works he produced during this period reveal the strong attraction he felt for his subjects.

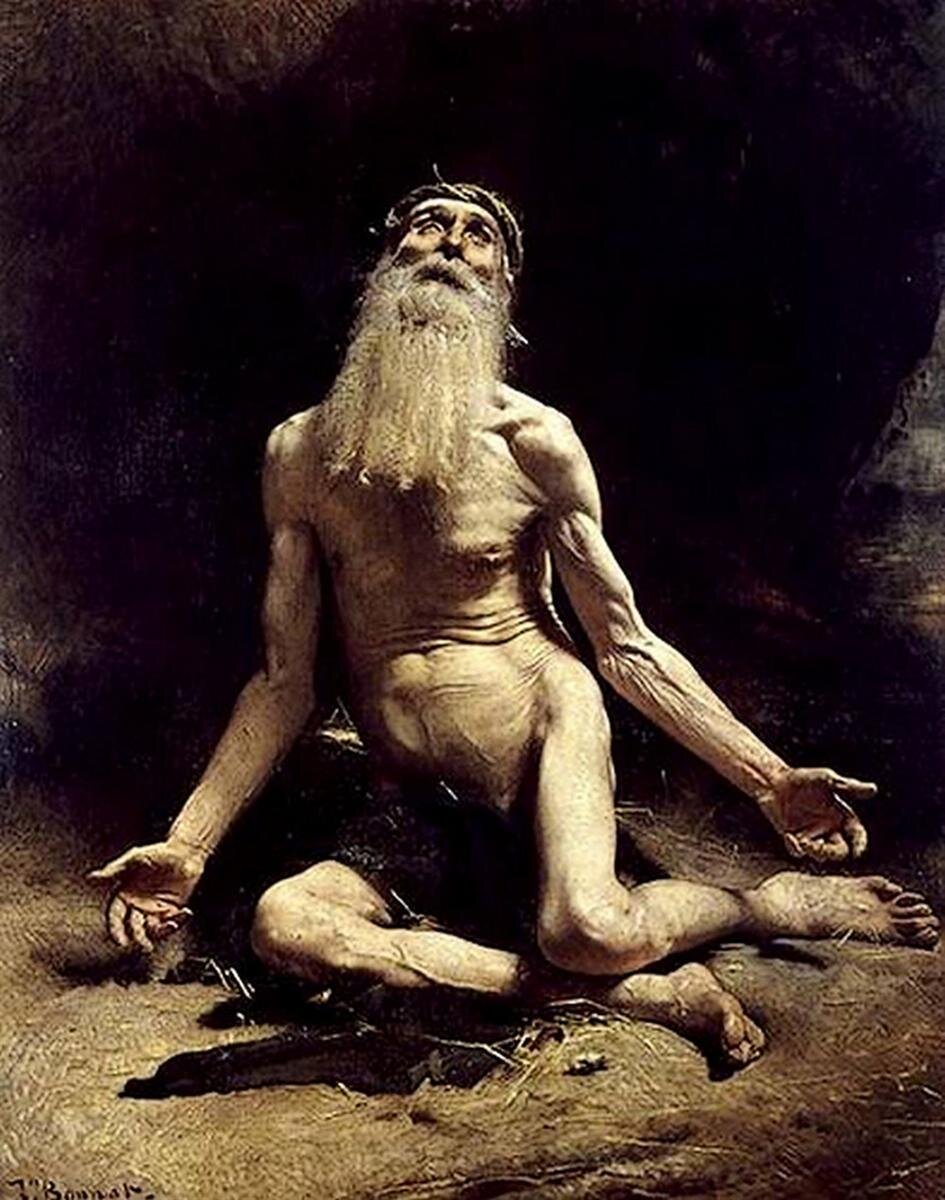

Job by Léon Bonnat, 1880

The Naked Truth

The third theme focused on “Nuda veritas, sans complaisance, The Naked Truth Without Compromise.” The idea of the authentic nude abandons the conventions of classical perfection to portray the body in realistic accuracy.

L’Age d’airain (The Age of Bronze) by Auguste Rodin, 1877

Homme au bain (Man at His Bath) by Gustave Caillebotte, 1884

What I like about Homme au bain (Man at His Bath) by Gustave Caillebotte is that it depicts a very private moment. A man is drying himself with a towel after a bath. His back is turned away from the viewer; he is neither posing for the painting nor has any intention of being seen.

David and Eli by Lucien Freud, 2004

The reclining nude male figure with the dad bod depicted in British painter Lucian Freud’s portrait David and Eli is his friend and studio assistant David Dawson. The dog is Eli, one of the artist's beloved whippets. Freud’s late nudes are noted for their uncompromising scrutiny of the human body. The artist utilized a technique known as impasto, where layers of paint and brushstrokes blend and converge to reveal the materiality of the flesh. The oil paint applied to the figure of David and the bedsheet beneath him was Cremnitz white, a type of white lead paint that Freud favored for its luminosity.

Jeune homme nu assis au bord de la mer (Young Male Nude Seated Beside the Sea) by Hippolyte Flandrin, 1836

Vitalism: Naughty by Nature

“Im Natur, In Nature,” the fourth theme is all about men en plein air, as they say in France. As the 19th century world became increasingly industrialized, academies across Europe favored realistic subjects, and people embraced vitalism, an anti-mechanical return to nature. This movement encouraged male nakedness during outdoor activities, including bathing, as a means to rejuvenate the spirit and increase virility.

The Fisherman With a Net by Frédéric Bazille, 1868

There’s an underlying eroticism and intimacy to The Fisherman With a Net by Frédéric Bazille. Whether unintentionally homoerotic or not, the subject in the foreground of the painting is an athletic young man prepared to cast a net into a pond. He’s clearly positioned to show off his “assets” and looks every bit like a modern-day hipster — all that’s missing is a pair of skinny jeans and a PBR. Another man in a state of undress can be seen in the background.

Mort pour la patrie (Dying for the Fatherland) by Jean-Jules-Antoine Lecomte du Nouÿ, 1892

This Mortal Coil

We continued wandering the galleries until we came to the one titled “Dans la douleur, In Pain,” which focused on the fragile balance of life and death. Man is not immortal; these works of art were a grim reminder of the shortness of life and the frailties of the mind and body.

Kneeling Nude With Raised Hands (Self-Portrait) by Egon Schiele, 1910

Egon Schiele is famous for his raw figurative works. A protégée of Gustav Klimt, Schiele had a muse and lover named Walburga “Wally” Neuzil, who had previously modeled for Klimt. Schiele’s color palette and expressive drawings remind me of French artist Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Where Lautrec elevated the world of underground nightlife, Schiele’s art was an exploration of the human condition, often depicting the twisted bodies and raw sexuality of his subjects.

In Kneeling Nude With Raised Hands, Schiele offers himself up to the viewer. The angst of his contorted, angular body, jaundice-colored flesh and red-rimmed eyes certainly questioned the artistic conventions of gender, sexuality and morality of pre-war Vienna. His hands and limbs appear to be pressed firmly against an invisible surface, possibly a mirror, while the negative space outlining Schiele’s form serves as a window for his figure to float in space and time.

L’Abîme (The Abyss) by Just Becquet, 1901

La mort d'Hippolyte (The Death of Hippolytus) by Joseph-Désiré Court, 1825

Homosexuality: The Object of Desire Laid Bare

The final room explored the theme “L’Objet du désir, The Object of Desire,” and focused on the more contemporary subtext of homosexual desire and objectification. A notice outside stated that some viewers may find the artwork beyond too provocative or offensive — but of course Wally and I found this titillating and weren’t in the slightest bit deterred.

Der Wäger (The Wager) by Arno Breker, 1939

Upon entering the space, we were greeted by a life-size nude male bronze figure by German sculptor Arno Breker. Called Der Wäger (The Wager), the figure stands chest out, looking every bit like a vintage beefcake photo from the 1940s. His hand is placed on his hip in an unintended effeminate manner. The sculptor’s neoclassical style made him a favorite of Adolf Hitler, who felt Breker’s works embodied fascist Nazi ideology.

Achille by Pierre et Gilles, 2004

David et Jonathan (Jean-Eves et Moussa) by Pierre et Gilles, 2005

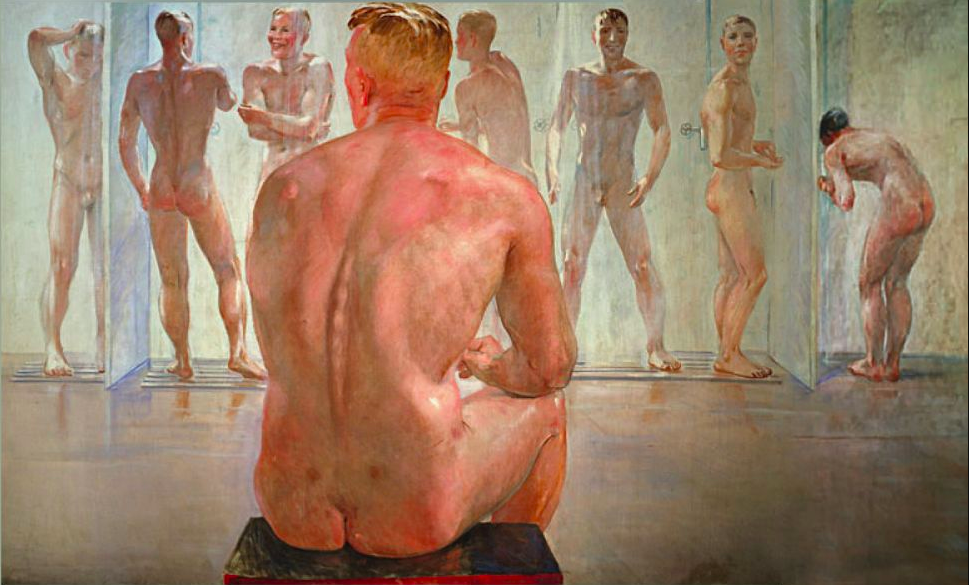

La douche, Après la bataille (Shower, After the Battle) by Alexander Deyneka, 1942

La douche, Après la bataille (Shower, After the Battle) by Alexander Deyneka was inspired by a black and white photograph of presumably nude athletes that Soviet photographer Boris Ignatovich had presented to Deyneka. It took the painter five years to complete. The provocative work depicts a group of strapping young men taking a communal shower. The muscular back of an onlooker is seen in the foreground. For me, the painting brings back high school anxieties of showering and sharing the locker room with the wrestling team. There’s a tension between heterosexual aspirations and homoerotic desire.

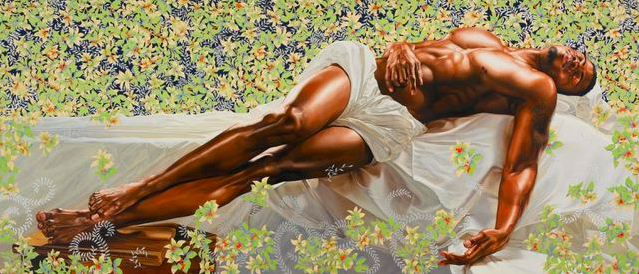

Death of Abel Study by Kehinde Wiley, 2008

Kehinde Wiley is a contemporary African American artist known for his large-scale paintings that highlight the image and status of young urban Black men in contemporary culture by placing them in scenes that are regal and European in origin. His photorealistic compositions reinterpret classical portraiture and are often combined with layered, vivid ornamental motifs. Gazing at the monumental Death of Abel Study — it measures a whopping 11 feet high by 25 feet wide — I couldn’t help but ask myself, is the man dead, being objectified, or both?

Incidentally, Wiley was the first Black gay artist selected to paint a presidential portrait. He was commissioned in 2017 to paint a portrait of former President Barack Obama for the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery.

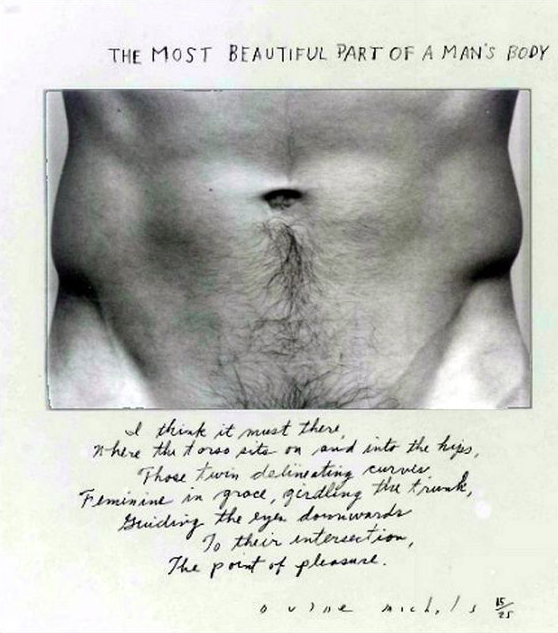

The Most Beautiful Part of a Man's Body by Duane Michals, 1986

Le Sommeil d’Endymion (The Sleep of Endymion) by Anne-Louis Girodet, 1791

There really wasn’t anything too outrageous to be seen as we wandered through Masculin/Masculin, but it was refreshing to view the galleries of traditional paintings, sculptures and contemporary works that examined and objectified men for a change. –Duke