The Bahamian artist is redefining portraiture — and Black women representation at museums like the Art Institute of Chicago — one stitch at a time.

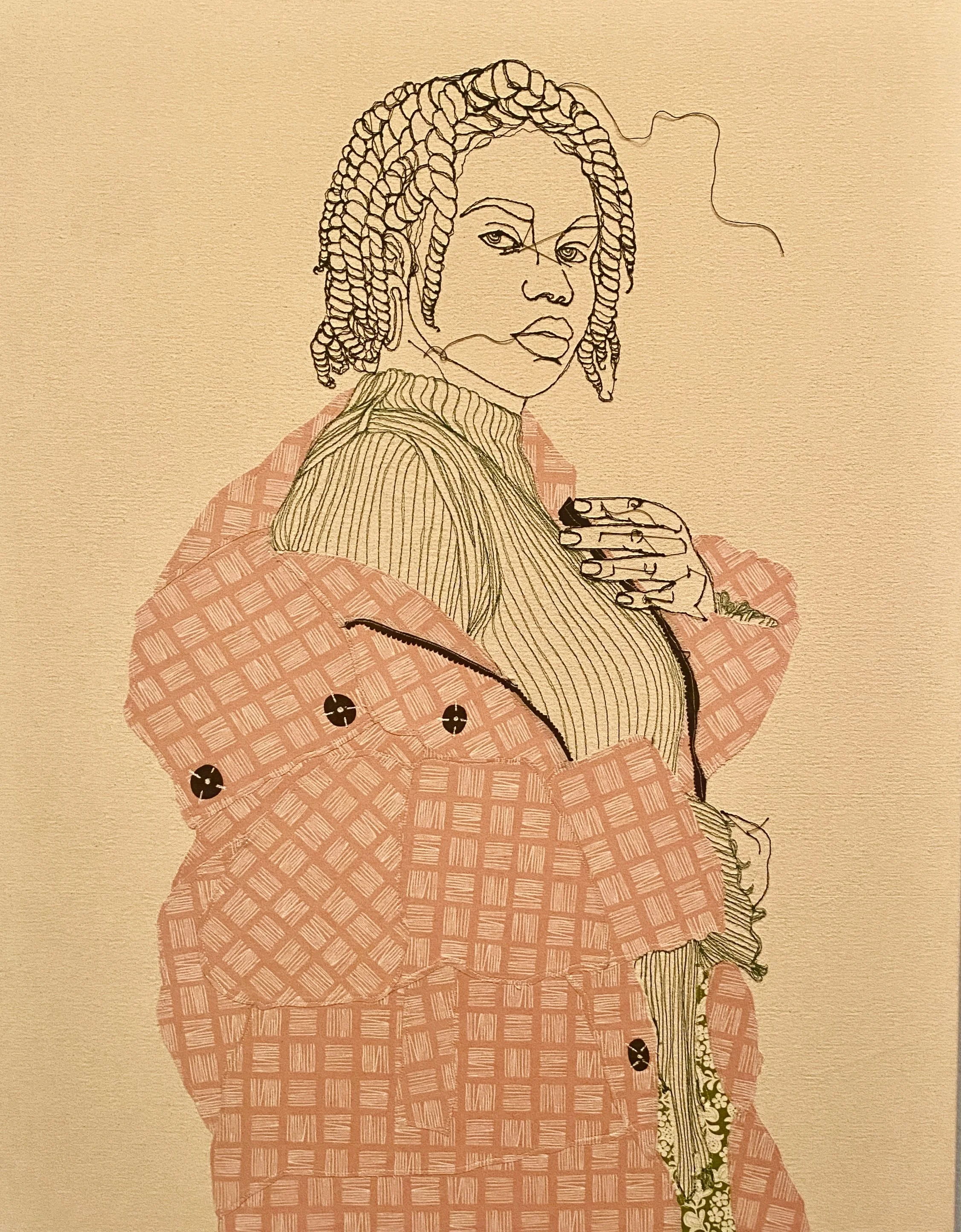

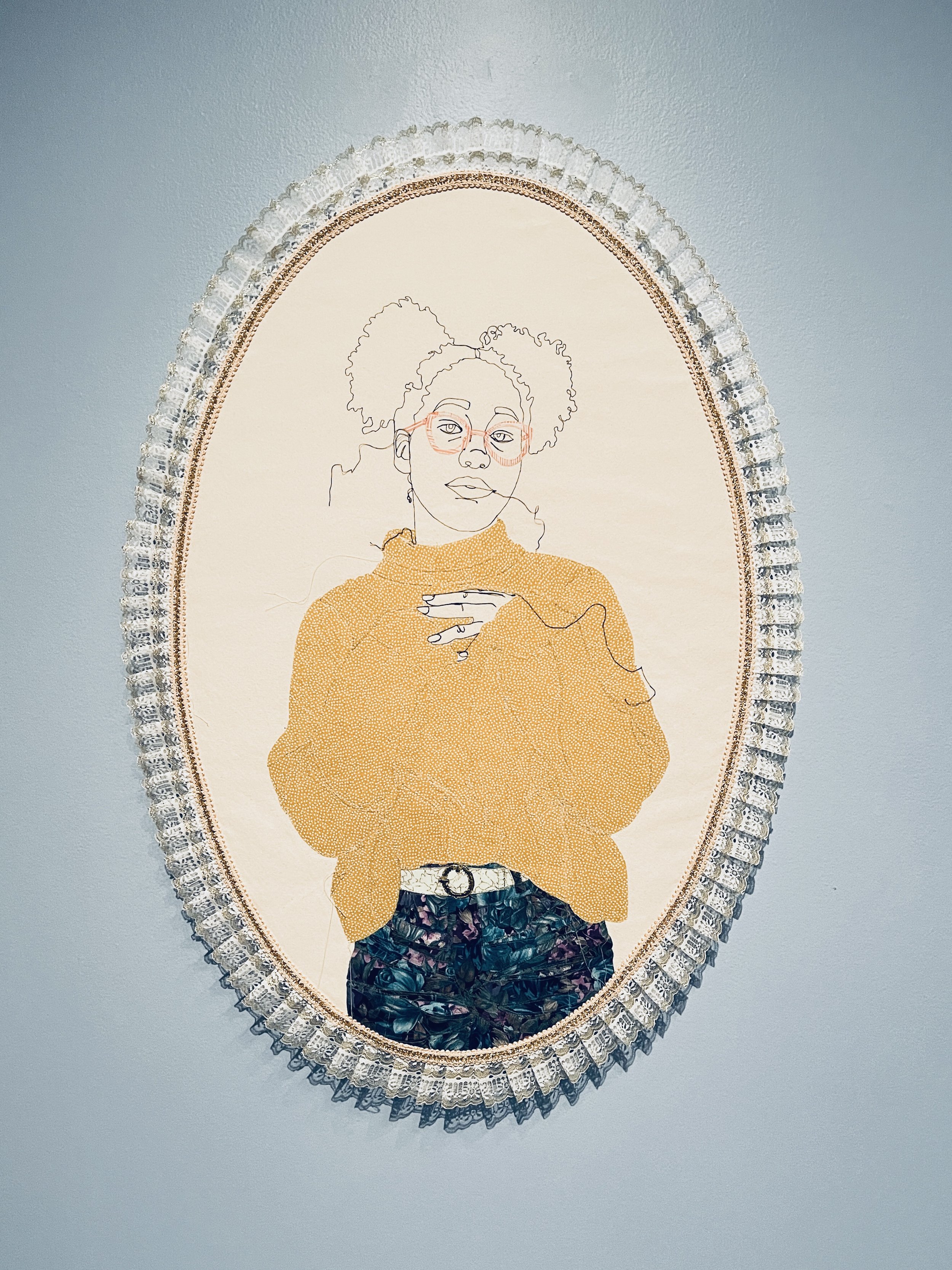

Gio Swaby’s textile portraits feature confident Black women, mixed fabrics and loose strings to juxtapose strength with so-called imperfections.

When you think of portraits, a few formats probably spring to mind: painting, photography, life drawing. But textiles?

That’s the medium Gio Swaby is rocking. The Bahamian artist uses textiles to create stunning portraits of powerful Black women.

“Textiles are a great way to connect with people because they’re so familiar.

Everyone has some sort of relationship with textiles, whether it’s through clothing or bedding or whatever. It’s something that we can all relate to on some level.”

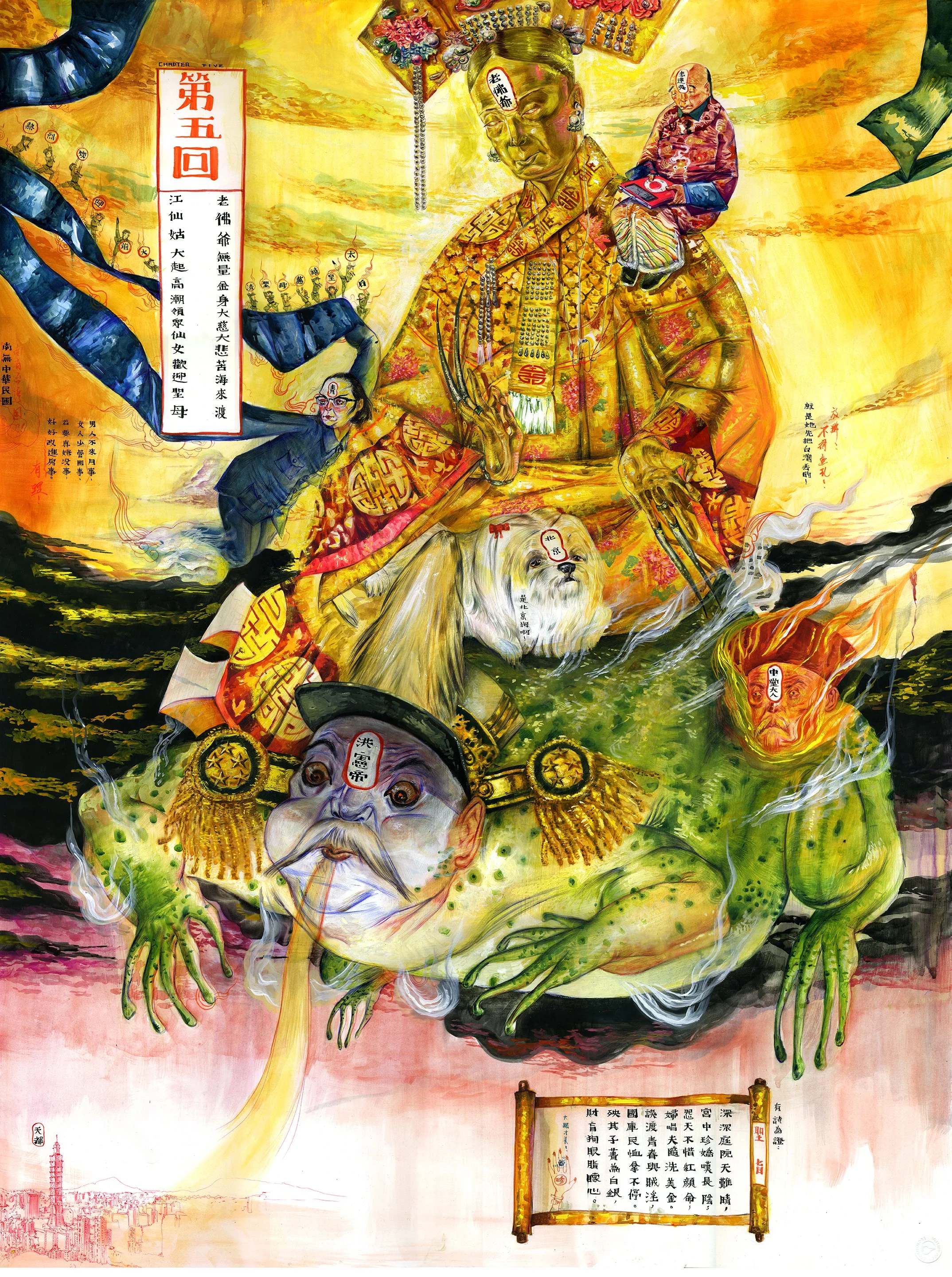

New Growth Second Chapter 11 from 2021

New Growth Second Chapter 9

Textiles were in part chosen for their familiarity, their approachability. Museum-goers can feel intimidated by fine art paintings, Swaby explains. The average person often thinks that they haven’t learned how to “properly” view a work of art.

But textiles don’t have that baggage. They’re comfortable; they’re part of our everyday lives.

“I think that textiles are a great way to connect with people because they’re so familiar,” Swaby says. “Everyone has some sort of relationship with textiles, whether it’s through clothing or bedding or whatever. It’s something that we can all relate to on some level.”

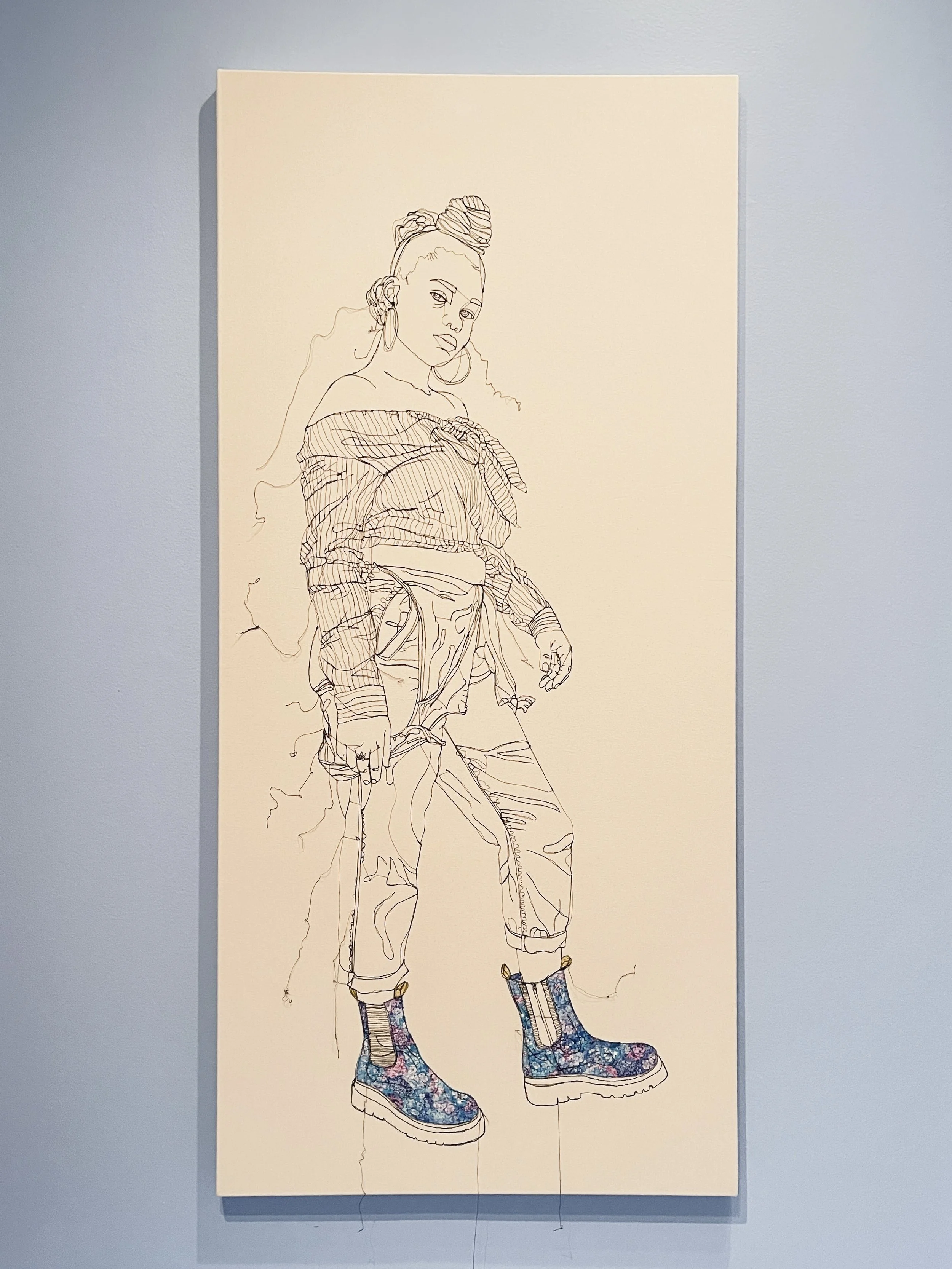

The Gylavantin’ series created in 2021

A Love Letter to Black Womanhood

Born in 1991 in Nassau, Bahamas, Swaby grew up with a seamstress mother who taught her how to sew and inspired her artistic vision. She studied art at the University of the Bahamas, Emily Carr University of Art and Design and OCAD University, and now lives and works in Toronto, Ontario in Canada.

Swaby has described her work as a love letter to Blackness and womanhood, a celebration of personal style and identity, and a challenge to the stereotypes and expectations that often limit the representation of Black women in art. Her exhibition Fresh Up, which we saw recently at the Art Institute of Chicago, is her first solo museum show.

With each stitch and thread, Swaby masterfully brings to life the beauty and complexity of Black women in a way that’s both breathtaking and empowering.

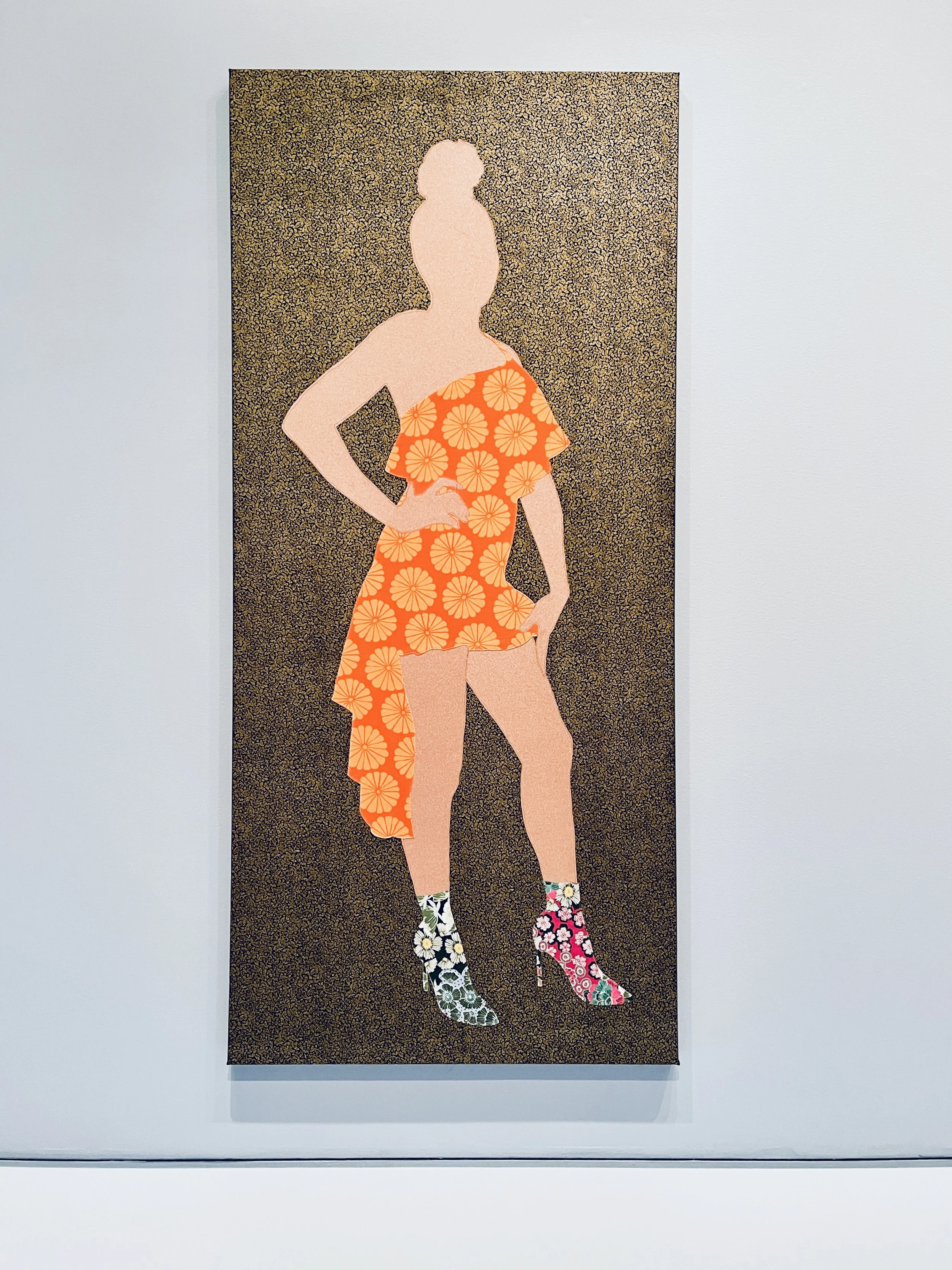

Another Side to Me Second Chapter 3 from 2021

Flipping Embroidery on Its Head

How does Swaby create her portraits? It all starts with a photo session. Swaby meets with her subjects, who are mostly Black women she knows personally or admired from afar, and engages them in a conversation about their lives, their dreams, their struggles and their joys. She then captures them on camera in a moment of self-awareness and empowerment, using natural light and simple backgrounds to highlight their features and expressions. She also impresses upon the subjects that the hairstyle, clothing and jewelry are essential elements of their personal style and identity.

“An important aspect for me is to ask the sitter to choose their own outfit,” Swaby tells us. “I think it’s so important to make that person feel comfortable. I want them to choose what they feel the most beautiful in and what makes them feel the most powerful.”

Going Out Clothes 3 from 2020

Once an image is chosen, Swaby transfers the images to fabric using a sewing machine. Yes, she actually does it all on a sewing machine! She uses a freehand technique that allows her to improvise and experiment with different colors and textures of thread.

“If I am feeling energized, I’ll start with the face or the hands,” Swaby says. “And if I’m not feeling the vibes, I will start with something that’s a little bit easier. Like if there’s a lot of stripes on the outfit. That’s pretty straightforward.”

Detail from the Gylavantin’ series

She also uses different types of fabric, such as cotton, denim, silk and velvet, to create contrast and depth.

Swaby says that she works intuitively and quickly. “I don’t like to overthink things. I like to just go with what feels right in the moment. What I want to capture is their true essence.”

Another Side to Me 2 from 2020

The final step is to flip the fabric over and present the reverse side of her work. This is where Swaby’s process becomes radical. Instead of hiding the stitching process, she exposes it and celebrates it.

“I wanted to have some moments of surprise, a new appreciation for the irregularities, the loose threads, the places where I lifted up the canvas before moving on to another area,” Swaby says. “I think there is beauty in imperfection. Why not celebrate it?”

Pretty Pretty 7 from 2021

She explains that this is a way of honoring the labor and care that goes into each portrait, as well as embracing the vulnerability and humanity of her subjects. It’s a way of challenging the expectations and stereotypes that often limit the representation of Blacks in art. She wants to show them as they are: beautiful but not idealized, complex but not exoticized, powerful but not threatening.

Pretty Pretty 5

The first time she displayed the underside of a stitched rendering was with her Another Side to Me series. “As textile-based makers, this is the part of our work that we tend to conceal,” she says. “I’ve always found a kind of beauty in these ‘flaws.’”

The New Growth series on display at the Fresh Up exhibit in Chicago

A Fresh Take on Collaboration for Fresh Up

Swaby’s exhibition Fresh Up is not just a collection of her works, but also a reflection of her vision and involvement. Swaby collaborated with the curators of the Art Institute of Chicago to create a show that showcases her range and diversity as an artist. The exhibition brings together seven of Swaby’s recent series, such as Love Letters and Pretty Pretty, along with approximately 15 new works, including her largest work to date, a commission for the U.S. embassy in Nassau.

An illustrated catalogue includes an interview between Swaby and Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones, as well as essays by the curators and contributions from Swaby herself.

Swaby joined the Art Institute team to stage the show and write the descriptions of the art. At the talk Duke and I attended with our friend, Ivan, the museum’s staff kept gushing about how awesome it was to work with a living artist, to have the opportunity to install an exhibit with the artist’s input.

The feeling was mutual: “Being able to work with the conservation team was one of the most exciting parts about having this exhibition here and being able to be here in person to see how it all works,” Swaby says.

Love Letter 8 from 2021

The title of the exhibit, Fresh Up, is a Bahamian phrase used as a way to compliment someone’s style or confidence — elements Swaby wants to highlight in her subjects. It’s a phrase that exudes positivity, joy and self-love.

“Life has so many variations — why not have this moment of representing and being able to celebrate many different kinds of people and also highlight the fact that Black women are not monolithic?” Swaby says. “We are all different, unique individuals.”

Sew true! –Wally