Virgin births weren’t unusual in pagan times — just in the Judeo-Christian tradition. Here’s how sex got tangled up with the idea of sin, and by extension, chastity became the ultimate sign of virtue.

Nativity, Birth of Jesus by Giotto, circa 1305

Early Christians needed their savior to have been born of a woman without sin, and that included the act of fornication. Greek myths could have influenced their theology.

Mary, the mother of Christ, is held up as one of a kind among humans for getting pregnant and giving birth without ever having sex.

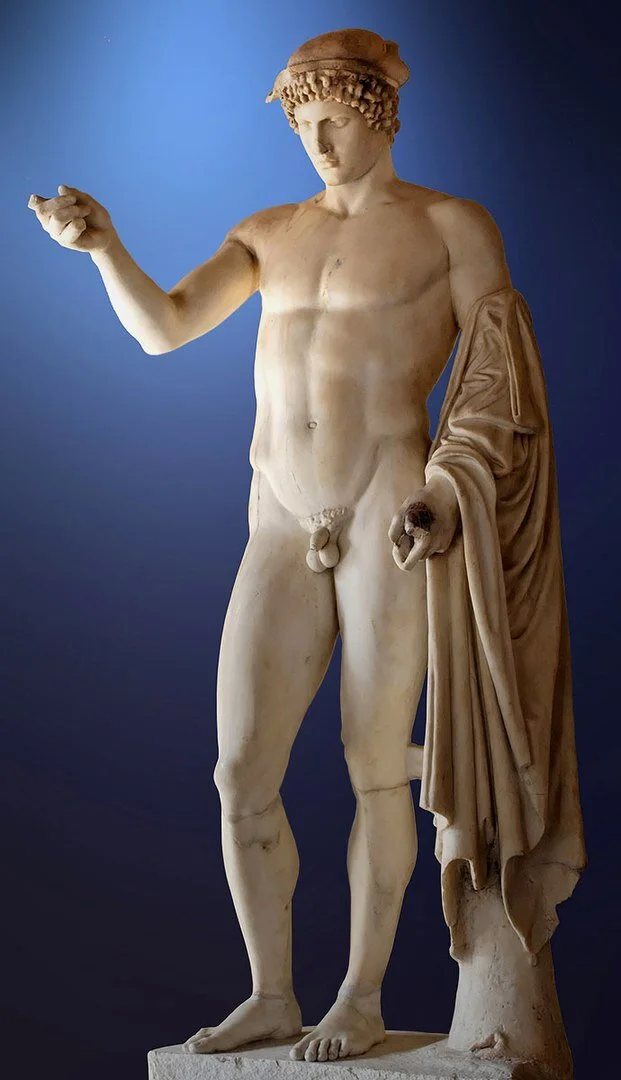

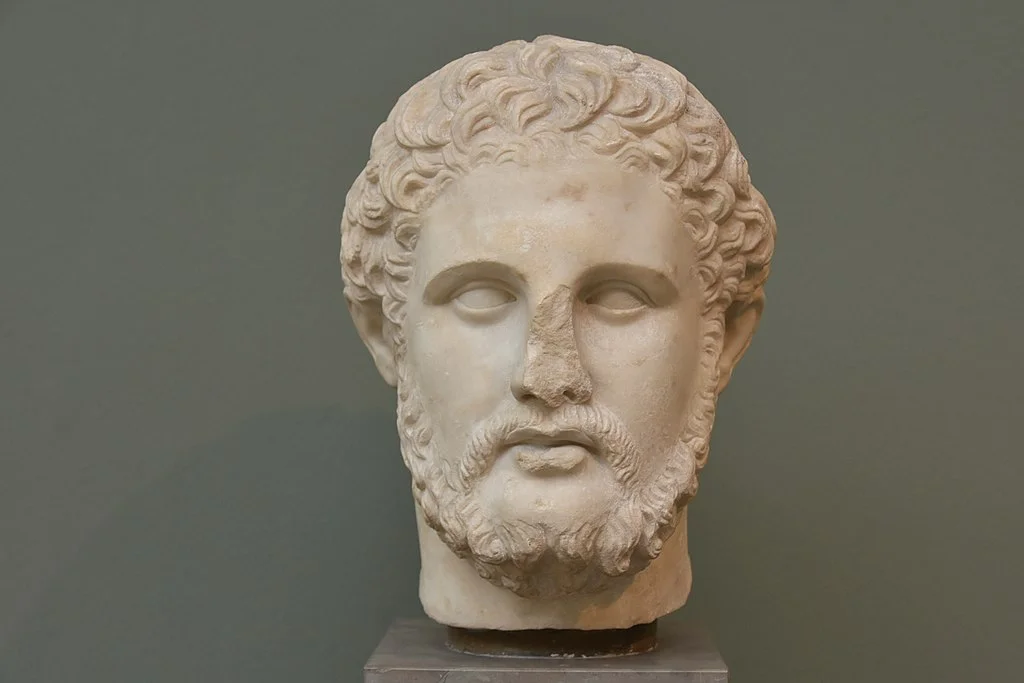

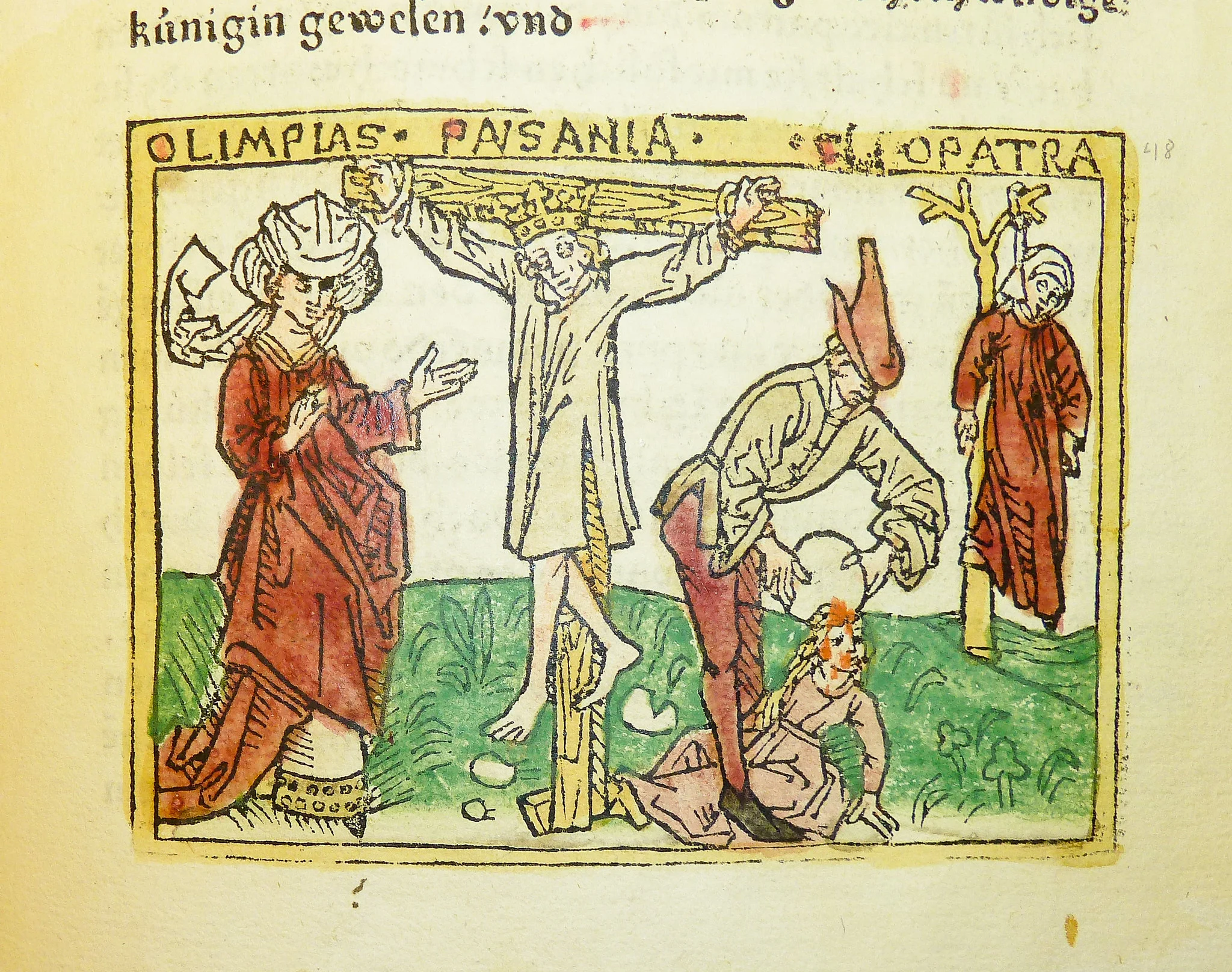

But believe it or not, so-called virgin births weren’t uncommon in the pagan world. Pythagorus, Plato and Alexander the Great were all said to have been born of virgins by the power of a holy spirit.

Alexander the Great’s mom dreamed of a lightning bolt striking her vagina — and lo and behold! She became pregnant with the future king of Macedon. In antiquity, “virgin” births weren’t all that uncommon.

“Christians, aware of the antique pantheon, are still worried by the parallel between Christ’s story and the dozens of virgin births of classical mythology,” Maria Warner wrote in her 1976 work Alone of All Her Sex: The Myth and the Cult of the Virgin Mary.

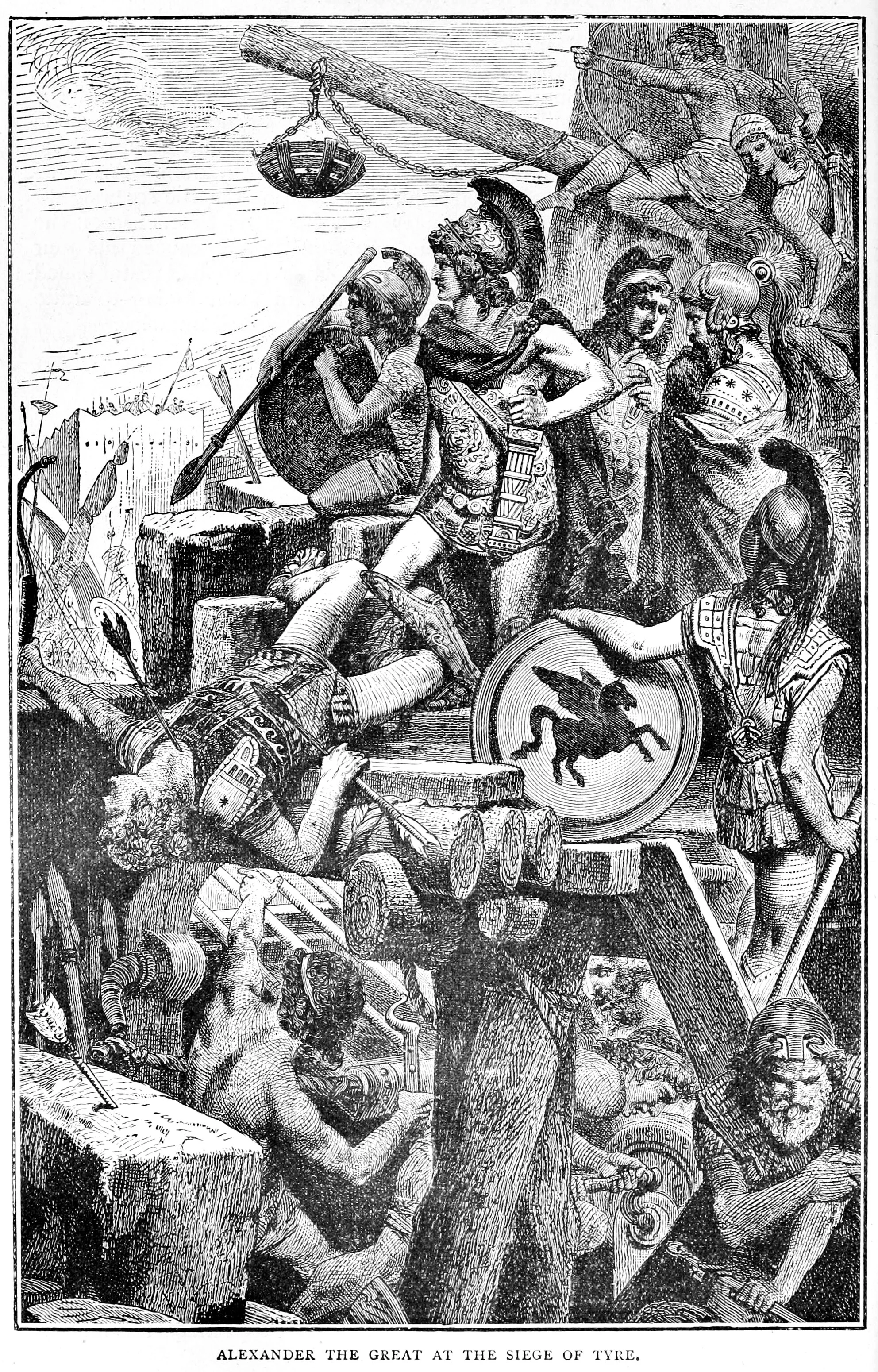

So how exactly does one conceive without fornication? We can turn once again to paganism. In Greek mythology, the closest parallel seems to be when Zeus turned himself into a shower of gold and impregnated Danae, who gave birth to the hero Perseus.

Danaë and the Golden Shower by Andrea Casali, circa 1750

The Greek myth of Zeus impregnating a woman in the form of a golden rain could have inspired the form the Holy Ghost took with the Virgin Mary.

The Greek god Zeus metamorphosed into a swan to couple with Leda. Did this bird imagery inspire the Holy Ghost’s representatoin as a dove?

Then again, the Holy Ghost is often depicted as a dove, and in another encounter, Zeus, that shapeshifting, lecherous cad, adopted the form a bird as well: He became a swan to seduce (or, perhaps, rape) Leda, mother of Helen of Troy, the twins Castor and Pollux, and another daughter, Clytemnestra.

The Annunciation by Fra Angelico, 1445

The shaft of light symbolizing the Holy Ghost isn’t too different from Danae’s shower of gold. Notice the contrast of the Virgin with Adam and Eve being expelled from the Garden of Eden to the left.

Connecting Sex With Sin

Of course in these cases, Zeus is copulating with the women. It’s an act of lust, and, at least for the god, one of pleasure. That’s in stark contrast to the Christian idea of Mary’s conception of Jesus: She remains a virgin, her maidenhead unbroken, and there’s no animal-like rutting.

This was an essential part of the Christ story. The fathers of the Christian church connected sex with sin early on, taking their cue from Genesis and the Garden of Eden: Fornication becomes necessary for reproduction, and the pain of childbirth a curse that Eve, and all women to follow, must bear.

Sex was seen as the ultimate sin. Saint Augustine wrote in City of God, in 426, that the passion aroused by lovemaking was sinful — though the holy act of propagation was not. In a similar vein, he added, “We ought not to condemn marriage because of the evil of lust, nor must we praise lust because of the good of marriage.”

“[I]n this battle between the flesh and the spirit, the female sex was firmly placed on the side of the flesh,” Warner wrote. “For as childbirth was woman’s special function, and its pangs the special penalty decreed by God after the Fall, and as the child she bore in her womb was stained by sin from the moment of its conception, the evils of sex were particularly identified with the female. Woman was womb and womb was evil.”

The Annunciation from the Grabower Altar in St. Peter’s in Hamburg, Germany, 1383

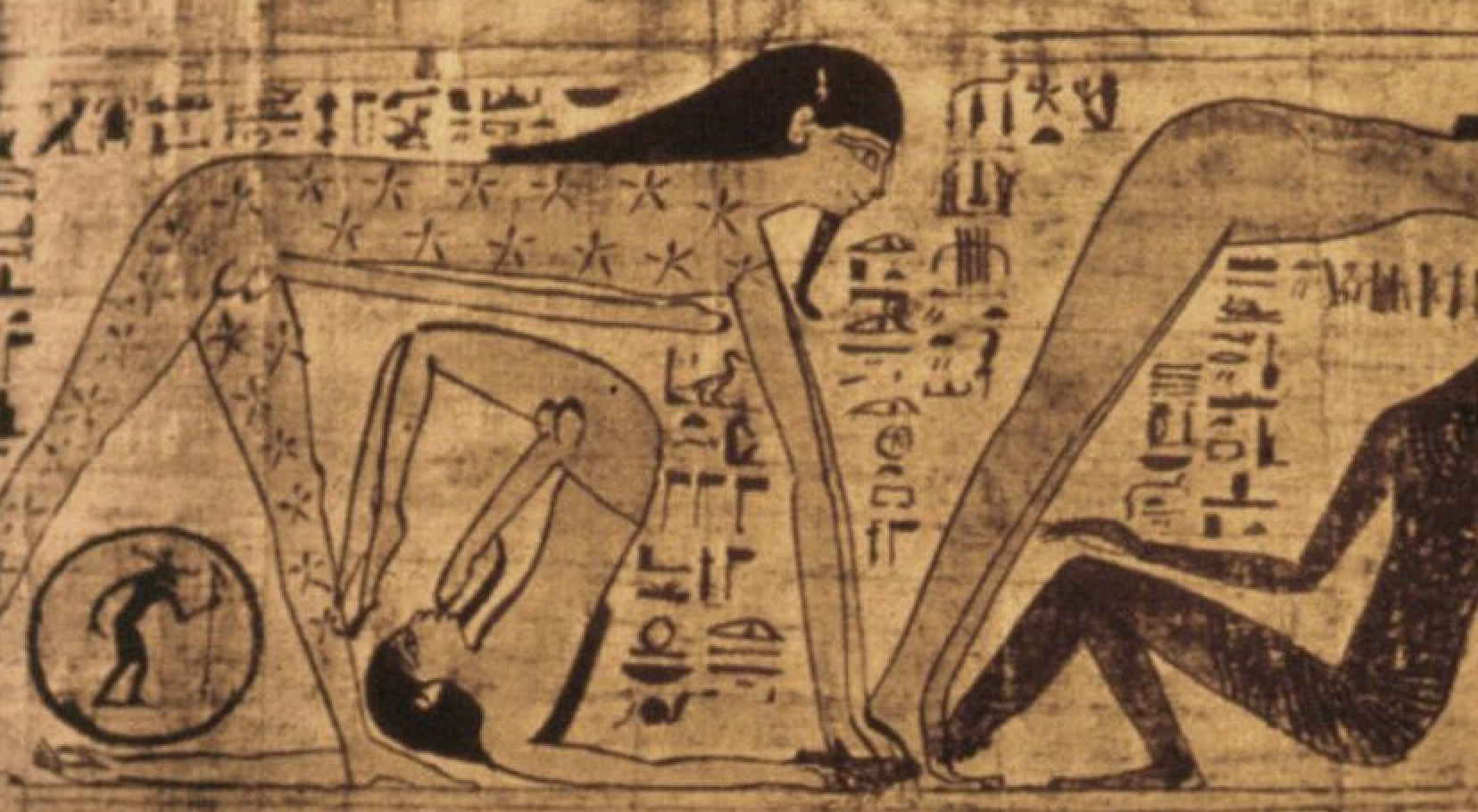

Saint Ephrem the Syrian wrote, “Perfectly God, he entered the womb through her ear.” The idea was that by conceiving via her ear, Mary remained a virgin.

The Virgin Mary: Not Your Typical (Sinful) Woman

Mary’s impregnation is, in contrast, a serene, holy act. It’s possibly tied to the very words of the Angel Gabriel when he announces her role in bringing forth the Savior. In ancient times, some people actually believed pregnancy could come about through the ear. (It gives a whole new meaning to Iggy Pop’s lyric “Of course I’ve had it in the ear before.”)

A sixth century hymn that’s still sung today goes:

The centuries marvel therefore

that the angel bore the seed,

the virgin conceived through her ear,

and believing in her heart, became fruitful.

The son of God chose to be born of a virgin, according to Augustine, because it was the only way to enter the world without sin. So, “Let us love chastity above all things,” he wrote, “for it was to show that this was pleasing to Him that Christ chose the modesty of a virgin womb.”

Painful births were one of God’s punishments for Eve eating the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil. But Jesus’ mother couldn’t be connected with anything so sinful, so she was said to be a virgin, pure and intact.

Slandering the Virgin Mary

The early Christian church had to defend itself against rumors that painted Mary in a negative light. Jews and pagans in Alexandria, for example, were saying that Jesus wasn’t conceived by God — instead, he was the bastard child of an incestuous union of Mary and her brother.

It doesn’t seem far-fetched nowadays to question a scientific impossibility — but at the dawn of Christianity, virgin births wouldn’t have been too big of a surprise. For early Christians, anything to do with female bodily functions was dirty and sinful. So they would have insisted their savior had to have come from an inviolate womb. And, despite evidence to the contrary, Mary became a virgin. –Wally