Manuel Jiménez is credited with starting the alebrije tradition in Oaxaca, but we’re smitten with the playful creations of Martín Melchor Ángeles.

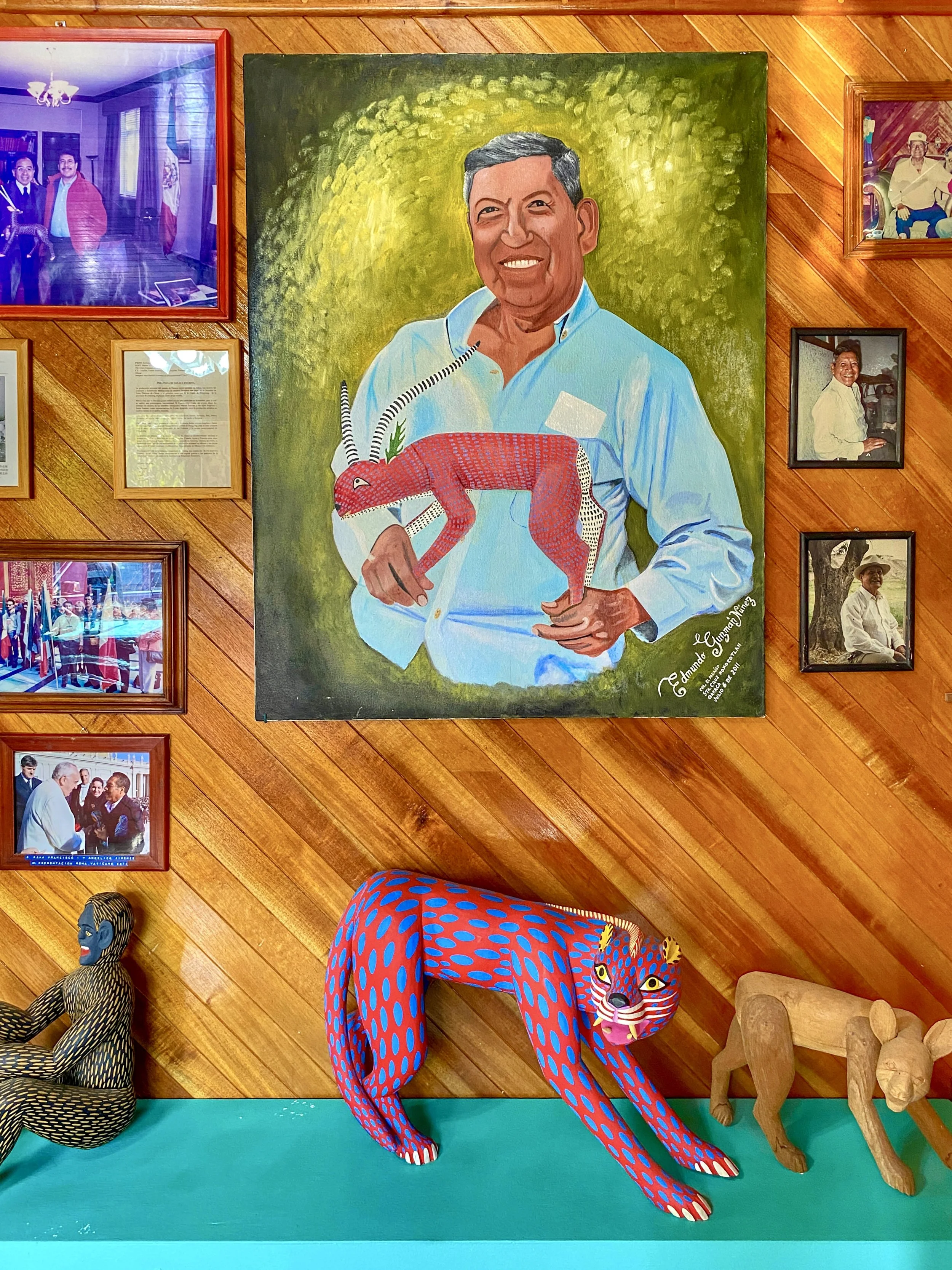

Don Manuel Jiménez is credited with bringing the alebrije tradition to Oaxaca, and shifting the medium from papier-mâché to wood.

On our fifth day in Oaxaca, Wally and I were picked up outside Casa Antonieta, the hotel we were staying at, by folk art expert extraordinaire Linda Hanna. Having done our research, we knew that Oaxaca was famous for its brightly painted collectible wooden figures and that Linda was the perfect guide to explore the region. We were on the road by 9:30 a.m. and en route to San Antonio Arrazola, a small pueblo where the tradition began.

These wood carvings are the newest of the local crafts yet draw on generations of skill. Even the capital’s fútbol (soccer) team, Los Alebrijes, is named after the locally produced wood carvings, which are an important source of income for their indigenous makers. According to Linda, prior to the 1940s, the region produced utilitarian items such as wooden spoons and molinillos, a utensil used to froth drinking chocolate.

Alebrijes are believed to have been modern offshoots of nahuals, human-headed animal amulets worn by the Zapotec.

The origin story that Linda has heard often and which she believes to be the most credible involves a Zapotec tradition: Every baby was given a small nahual or nagual (pronounced “na-wal”) amulet to wear around their neck from the day they were born. These tokens took the form of animals from the 20-month Mesoamerican zodiac and were protective talismans symbolic of an individual’s alter ego that accompanied them throughout life.

Don Manuel is no longer living, but his family carries on the woodcarving legacy.

Don Manuel Jiménez: The Alebrije Story Begins

“Manuel Jiménez was a peasant farmer who would be out there in the fields,” Linda told us. “And I think these people are, you know, born with a machete nearby. So carving is almost inherent in their DNA, and he was probably out there whittling away. He didn’t want to be limited by the size of the creatures, so he started making them bigger. At some point he had a bunch of them and would come into town, sit on some street corner, trying to sell them, probably not too effectively — until an American saw his work and was very impressed.”

Alebrijes take many forms but are mostly animals nowadays. Jiménez liked to do human faces, inspired by an ancient Zapotec tradition.

If you’re into alebrijes even half as much as Wally and Duke, consider having Linda Hanna take you on a tour of woodcarving artisan workshop homes.

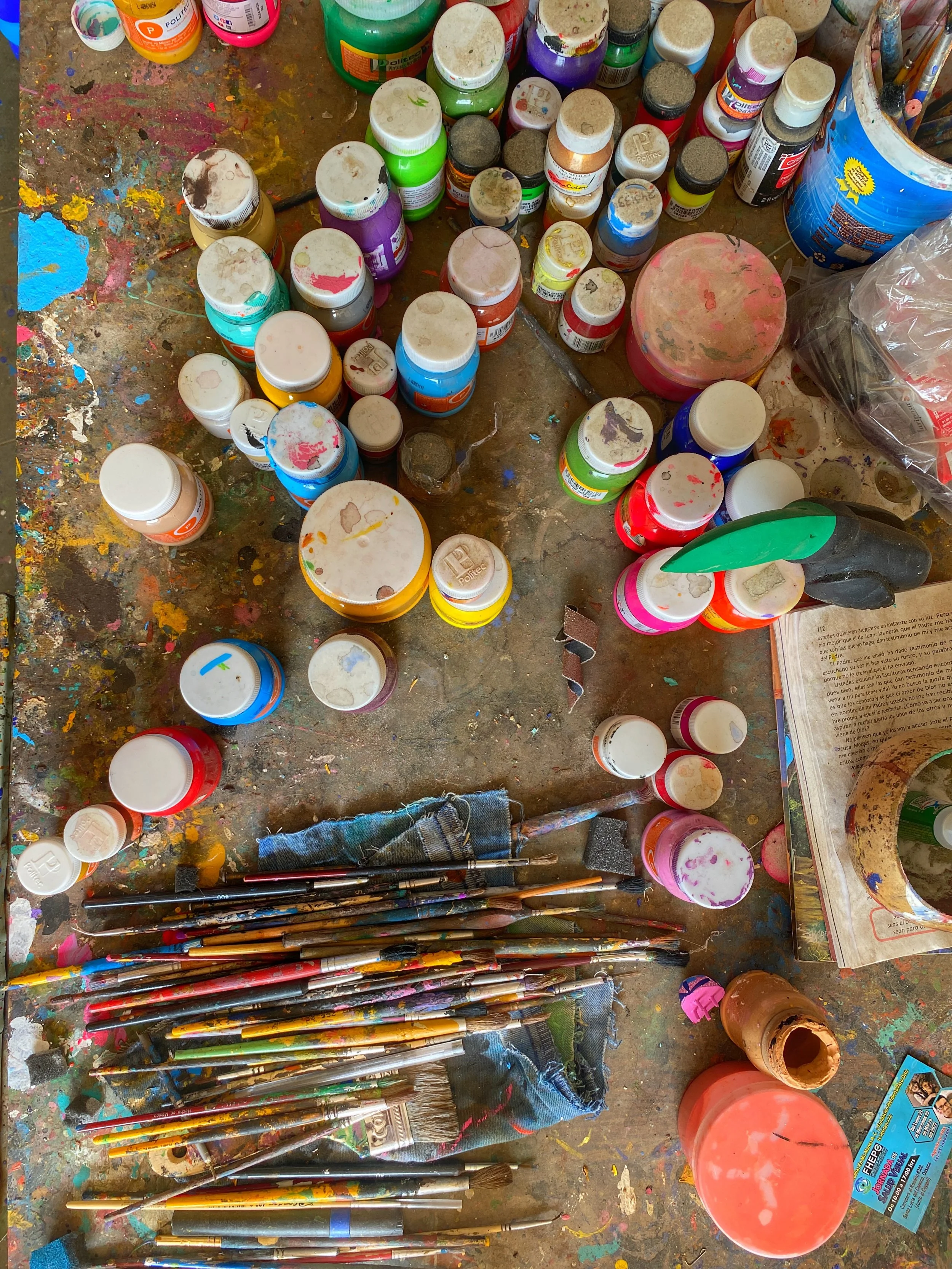

We call Jiménez and his cohorts woodcarvers — but a lot of their craft involves painting. Alebrijes are known for their surprising mix of colors and patterns.

Jiménez, with the assistance of the foreigner, took these objects and presented them to the offices of the Tourist Council in Mexico City. The closest thing they could compare them to were the fantastical creatures Pedro Linares had been making out of papier-mâché, so they decided to also call these surreal, vibrantly colored wooden adaptations “alebrijes,” too.

What’s an Alebrije? Learn more about our favorite Mexican artisan tradition.

Click here

About 45 minutes later, we were welcomed to Arrazola by a giant acid green praying mantis sculpture and a sign commemorating the town as la Cuña de los Alebrijes, the Cradle of Alebrijes. A short time after, we arrived at our destination, the museum workshop of the Jiménez family. Known locally as Don Manuel, the patriarch died in 2005 and is often credited as the father of Oaxacan alebrijes.

A fun sculpture of a giant praying mantis in Arrazola, the Cuña, or Cradle, of Alebrijes

As we parked and got out of Linda’s car, we noticed a man outside the studio enclosure with a converted bicycle grinding a metallic object against a spinning rust-colored disc. When we asked Linda what he was doing, she replied that he was a knife sharpener and it looked like he was working on a pair of scissors.

The charming courtyard at the Jiménez home, workshop and store

In the courtyard, a group of small, weathered and anatomically correct diablitos (little devils) playing guitars hung along a roughly textured stucco wall.

Inside the workshop are framed photographs, newspaper articles and nahuales. One with a man’s face and mustache was sitting upright like a dog, another, ears back, crouched, appearing ready to pounce. A brightly colored figurine of Dante, the dog from the Pixar movie Coco stood atop a well-worn table.

The taller (pronounced “tie-yair”), or workshop, is operated by Don Manuel’s sons, Angélico and Isaías, and contains a small museum with glass display cases of their father’s work. They still sign Manuel’s name to their work — supposedly to honor his legacy.

The patriarch specialized in nativity scenes, animals and nahuales. There’s even a children’s book, Dream Carver, that tells the story of a young woodcarver who breaks with a generations-old artistic tradition, inspired by the life of Don Manuel.

A display case of some of Don Manuel’s works and the children’s book based on his life

There’s a shop/museum connected to the workshop.

“When these started selling, Jiménez tried to keep it a secret — which is impossible in a little village,” Linda said. “They know everything about you, good and bad.”

It wasn’t long before campesinos (farmers) in the nearby pueblos of San Martín Tilcajete and La Unión Tejalapan caught on and decided to carve and sell their products to tourists and collectors from North America and beyond. A new artisan tradition was born.

When you see this mural, you’ll know you’re about to enter Don Manuel’s complex.

El Tallador de Sueños Museo-Taller

Álvaro Obregón #1

San Antonio Arrazola

Santa Cruz Xoxocotlán, 71233

Oaxaca

México

While we were in Arrazola, we stopped into Taller de Alebrijes Autóctonos, a massive store filled with colorful carvings.

Shopping Break

In addition to Don Manuel’s workshop and museum, Arrazola has a concentration of shops on Calle Emiliano Zapata. Wally and I stopped by Taller de Alebrijes Autóctonos, a massive establishment with a vast selection of alebrijes. Linda had mentioned that a few artists use syringes to apply dots of acrylic paint to the surface of their creations. Sure enough, I noticed a woman working on a piece who was using a syringe to embellish a small wood carving.

Taller de Alebrijes Autóctonos

Emiliano Zapata #2-B

San Antonio Arrazola

Santa Cruz Xoxocotlán, 71233

Oaxaca

México

Martín Melchor Ángeles, our favorite alebrije artisan

The Story Continues: Martín Melchor’s Magical Menagerie

The moment I first saw the work of Martín Melchor Ángeles on the Instagram feed of Mexico City-based freelance journalist Michael Snyder, I knew I’d found someone special.

Our next stop was the taller of Martín Melchor Ángeles. A dusty, rose-colored wall sported a hand-painted sign with one of Martín’s signature dalmatians wearing a red shirt and blue pants riding a bicycle.

Martín’s distinct whimsical handcarved animals include a menagerie of creatures: giraffes operating mototaxis, dogs on bikes, alligators in libraries, cows on stilts and more. His wife, Hermelinda, makes handsewn costumes for the figures on stilts.

These are the alebrijes on stilts that Duke and Wally bought at Melchor’s workshop.

The stilt walkers were included as part of a collaborative exhibit, Transcommuniality, by multidisciplinary artist Laura Anderson Barbata, which made an appearance at the Museo Textil de Oaxaca in 2018. The traveling exhibit includes interpretations of stilt walkers’ costumes found around the globe, from the moko jumbies of Trinidad and Tobago to the Zancudos de Zaachila in Oaxaca.

In fact, while walking through Oaxaca Centro a couple days earlier, Wally and I happened upon a parade with these performers. We marveled at how they danced around, tied onto wooden stilts. They’re known as Zancudos, which comes from zanco, meaning “stilt” but also evokes “mosquito” — a reference to the insects’ long legs. The male performers, some dressed in masculine garb, some wearing dresses, are impressive to watch.

Part of the fun of a folk art tour is seeing the handicrafts at various stages of production.

At Martín’s shop, it was difficult to decide between the pieces. But ultimately, we decided upon a bull dressed as a tiliche in colorful scraps of cloth. This character makes an annual appearance at Guelaguetza, a celebration of indigenous culture held in Oaxaca de Juárez, along with an alligator in fanciful Tehuana dress wearing a lemon yellow huipil tunic paired with a long bougainvillea pink skirt.

If for some reason you don’t want to make a trip to Martín’s studio (and want to pay a lot more for his work), we found a couple of his pieces in town along Avenida de la Independencia at Andares. But not only is it cool to meet these artisans and see their workshops, you’ll find the prices much cheaper than those at the stores.

The sign at Martín’s home and workshop shows his playful style, often with animals on bikes or in mototaxis.

Martín Melchor Ángeles

Andrés Portillo #2

San Martín Tilcajete

Oaxaca

México

Wally and I wished that we had allotted extra time in Oaxaca to coordinate a second day trip with Linda. Her involvement with and passion for the region’s indigenous artisans deepened our understanding and appreciation of the process. Having her as both driver and guide took the stress of transportation out of the equation. Plus, her familiarity with and ability to contact the creators prior to us visiting their workshops ensured that they had pieces for us to see and purchase.

If you’re interested in Mexican folk art, Linda can introduce you to local artesanos and take you to see their workshops. Send her an email at folkartfantasy@gmail.com. —Duke