Was Tutankhamun murdered? Did he die from a chariot accident? Why is his tomb so unimpressive? We help solve one of the great mysteries of Ancient Egypt.

How did the most famous pharaoh of Ancient Egypt die? Recent evidence disproves some of the most popular theories

Tut’s mummy

Think of it as an Ancient Egyptian cold case. For decades there have been many competing theories about how Tutankhamun, the Boy King, died and why his tomb is smaller than that of other pharaohs. His cause of death has remained one of Ancient Egypt’s most enduring mysteries.

The mummy of Tutankhamun lies within his tomb in the Valley of the Kings, where it was discovered by Howard Carter. As far as we know, it’s the only mummy in the Valley of the Kings — most royal remains have been relocated to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

“Was Tut a victim of foul play, hit in the head with a blunt instrument, murdered by his uncle and successor, Ay? ”

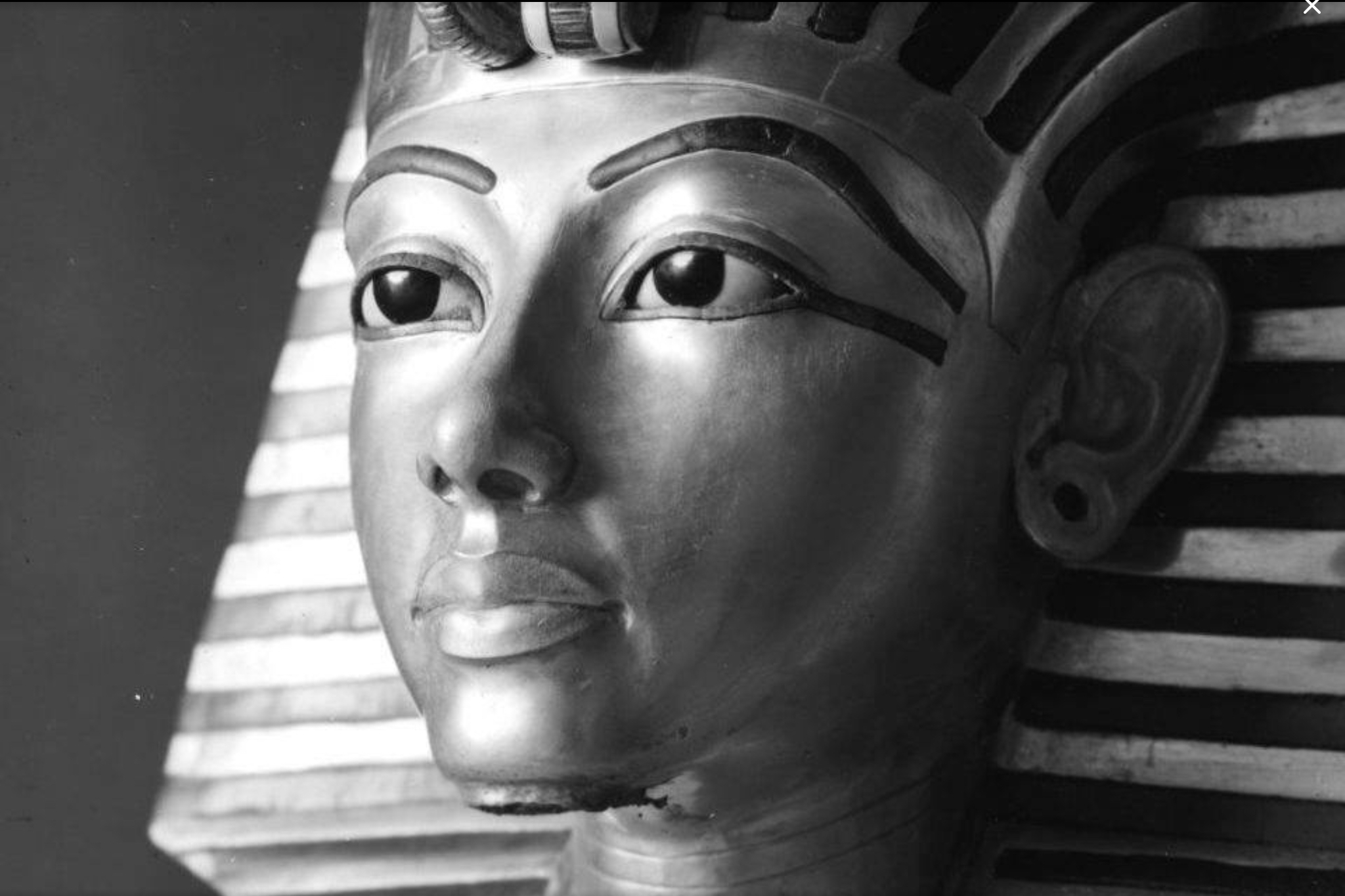

The resin used to preserve King Tut’s mummy actually ended up damaging it when Carter and his team removed the funerary mask

LEARN MORE: Ancient Egypt’s Mummification Process Explained

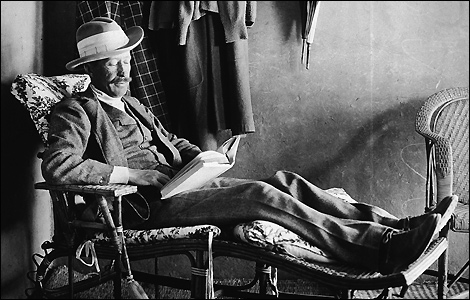

Carter, who discovered Tut’s tomb, unveils the mummy in 1925

Was the tomb cursed?

What’s it like to visit today?

EXPLORE King Tut’s Tomb

A Look at the Evidence

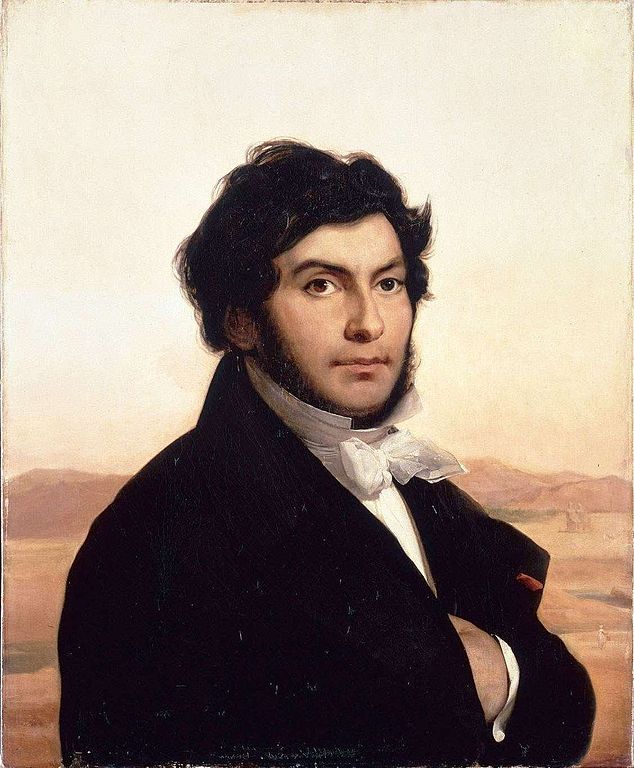

Tutankhamun’s mummy shows that he died when he was around 18 or 19 years old, but his death remains a mystery. Was he a victim of foul play, hit in the head with a blunt instrument, perhaps murdered by his uncle and successor, Ay?

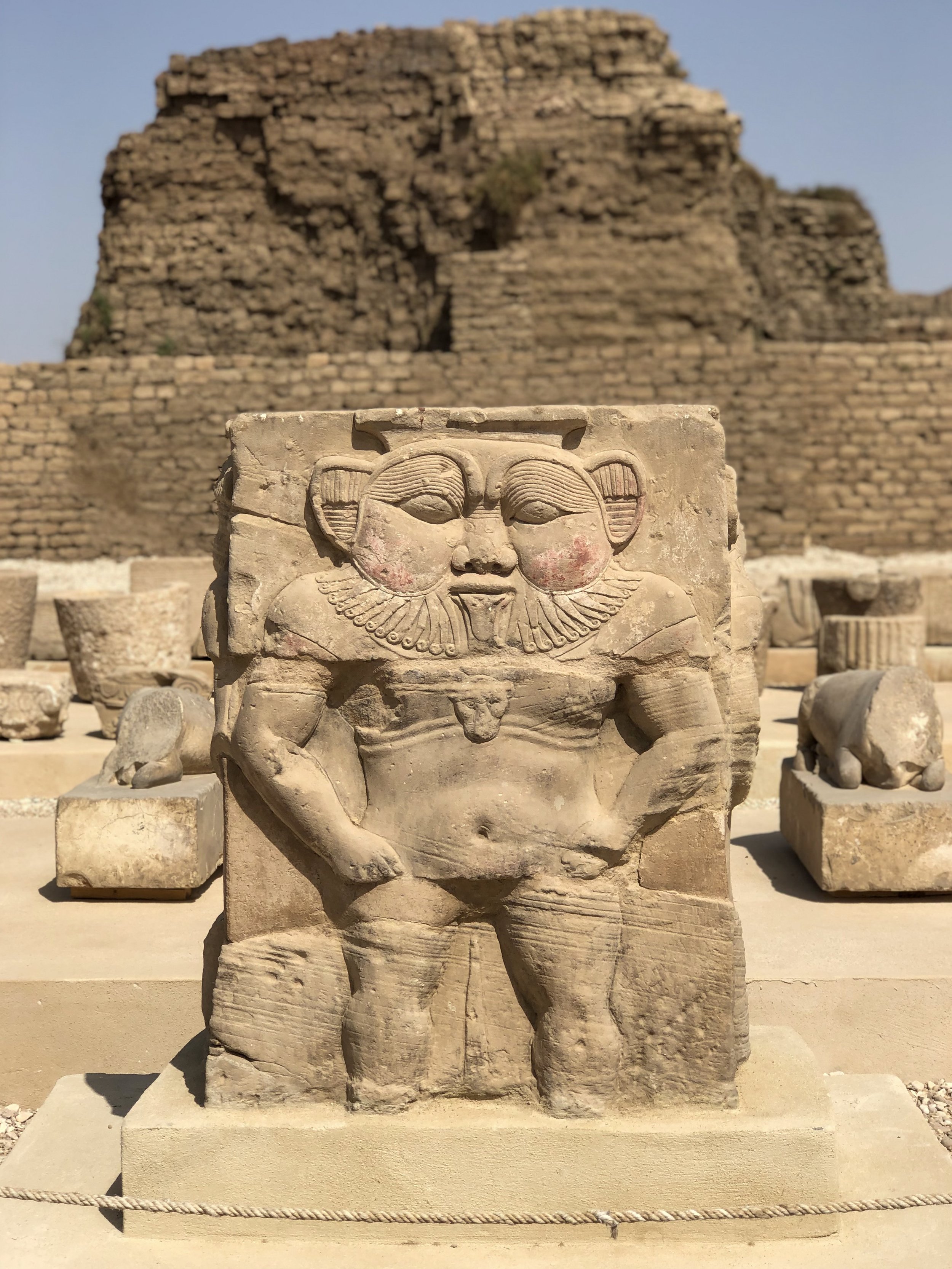

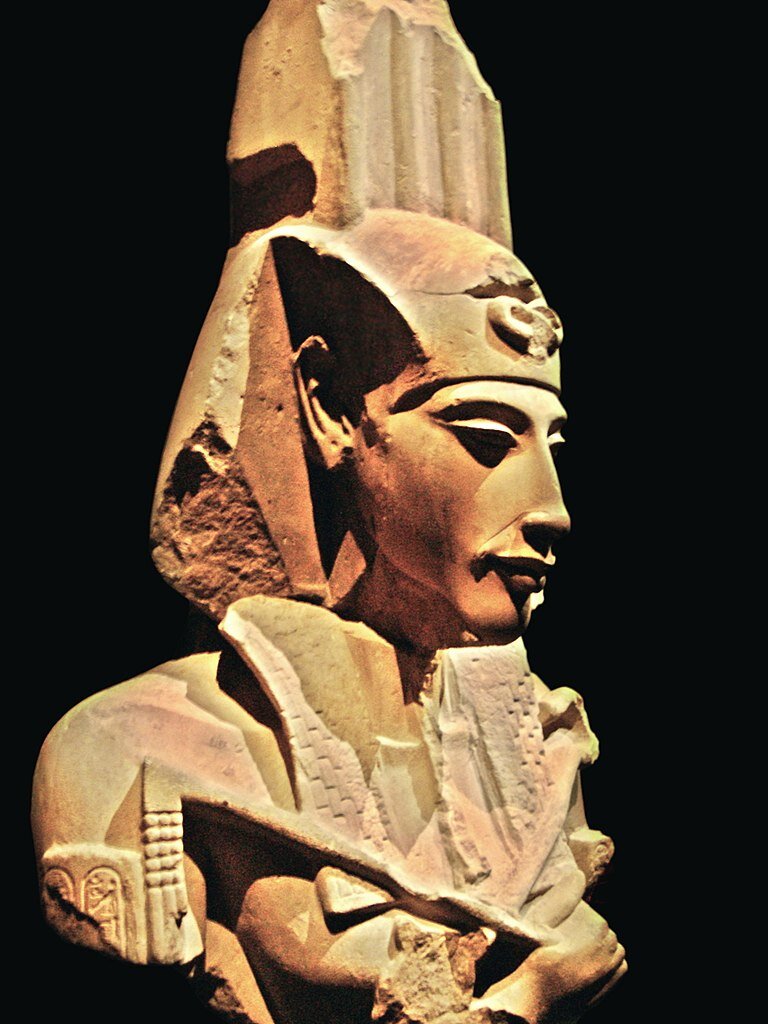

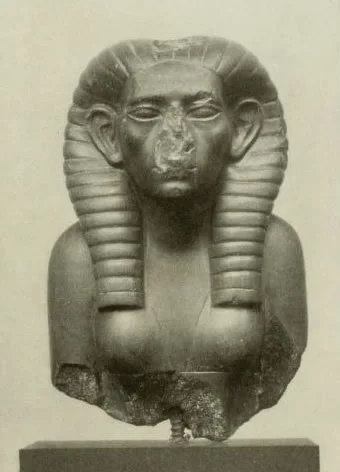

A carving of Ay from Amarna

This theory stemmed from X-rays taken in 1968 showing bone fragments in his skull. It’s now disproven — this damage actually occurred when Tut’s gold death mask was pried unceremoniously from his mummy by Carter and his team.

Was Tut in a chariot accident, trampled beneath the hooves of his horses? Or perhaps he perished from an infection caused by a fractured femur that became gangrenous?

A replica of a chariot from Tut’s tomb — even though his bum foot should have prevented the young pharaoh from riding in one

One of these theories may be true. But in Ancient Egypt, where the average lifespan was about 30 years old, it wasn’t uncommon for people to die at a young age, even royals, who had a better chance at longevity than the general populace.

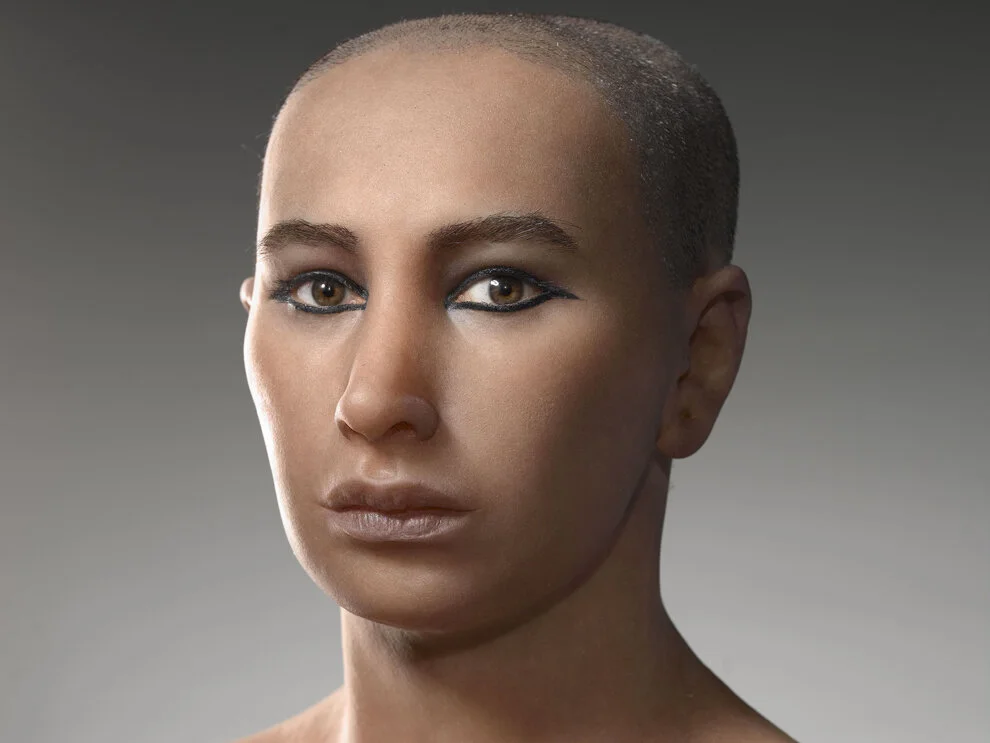

A reconstruction of what Tutankhamun probably looked like

Who says incest is best? Generations of inbreeding led to various maladies that Tut suffered from, including a bone necrosis in his foot

Tutankhamun suffered from a variety of maladies, including malaria and a crippling bone necrosis known as Kohler’s disease, that weakened his left foot. This makes it doubtful that he died from a chariot accident, as it would have been difficult for the young man to safely operate one. As a side note, 130 canes, many of them showing signs of use, were buried with King Tut.

The Egyptians believed that incest kept the bloodline pure, but it actually had the opposite effect, leading to his generally weakened state from genetic afflictions — problems likely exacerbated by malaria.

You’ll have to pay extra to visit Tut’s tomb in the Valley of the Kings

A Tomb Not Really Fit for a King

This brings us to the question of why Tut’s tomb is so meagre in size compared to that of his fellow pharaohs. Was he placed in there because he died suddenly, at a young age?

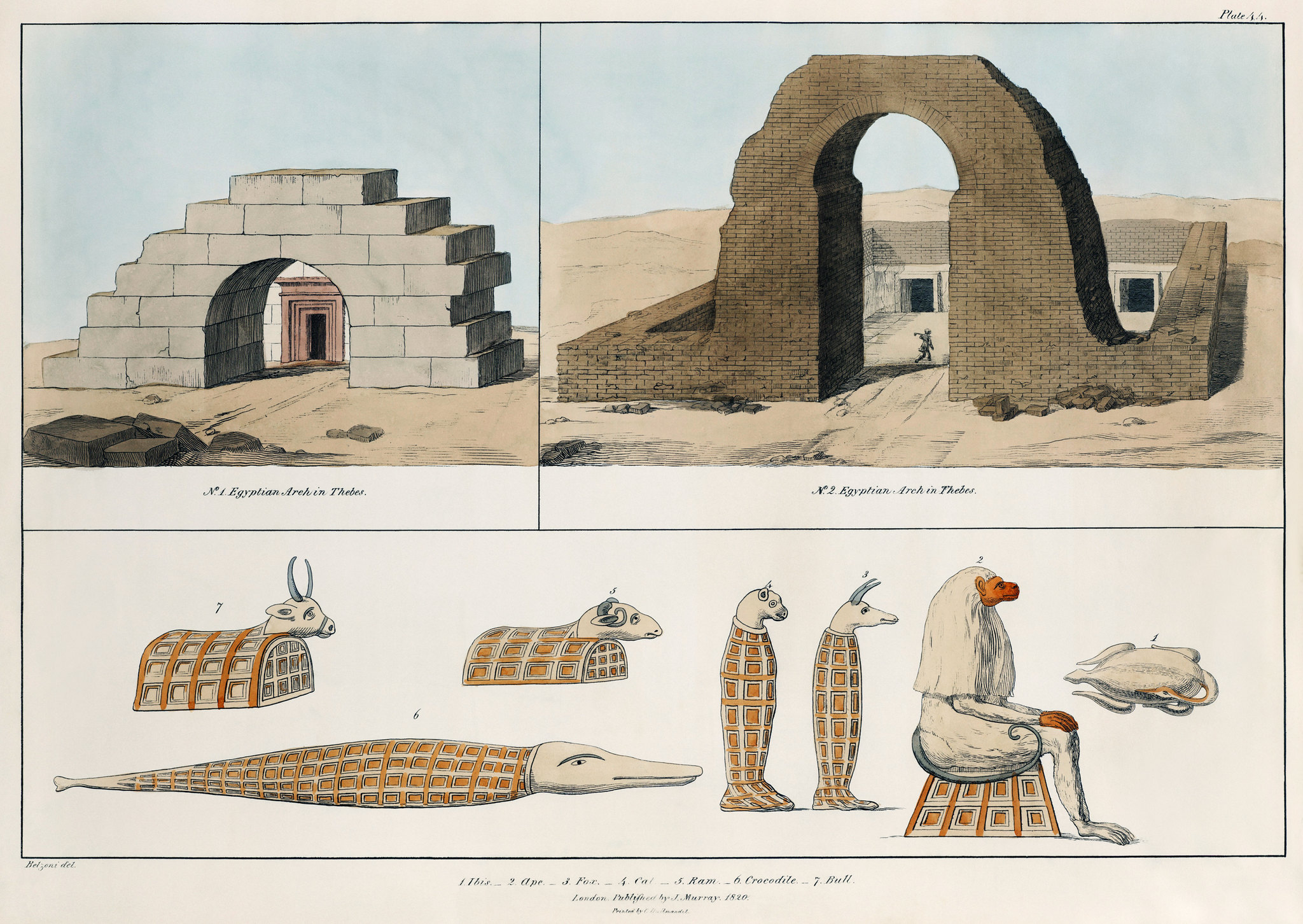

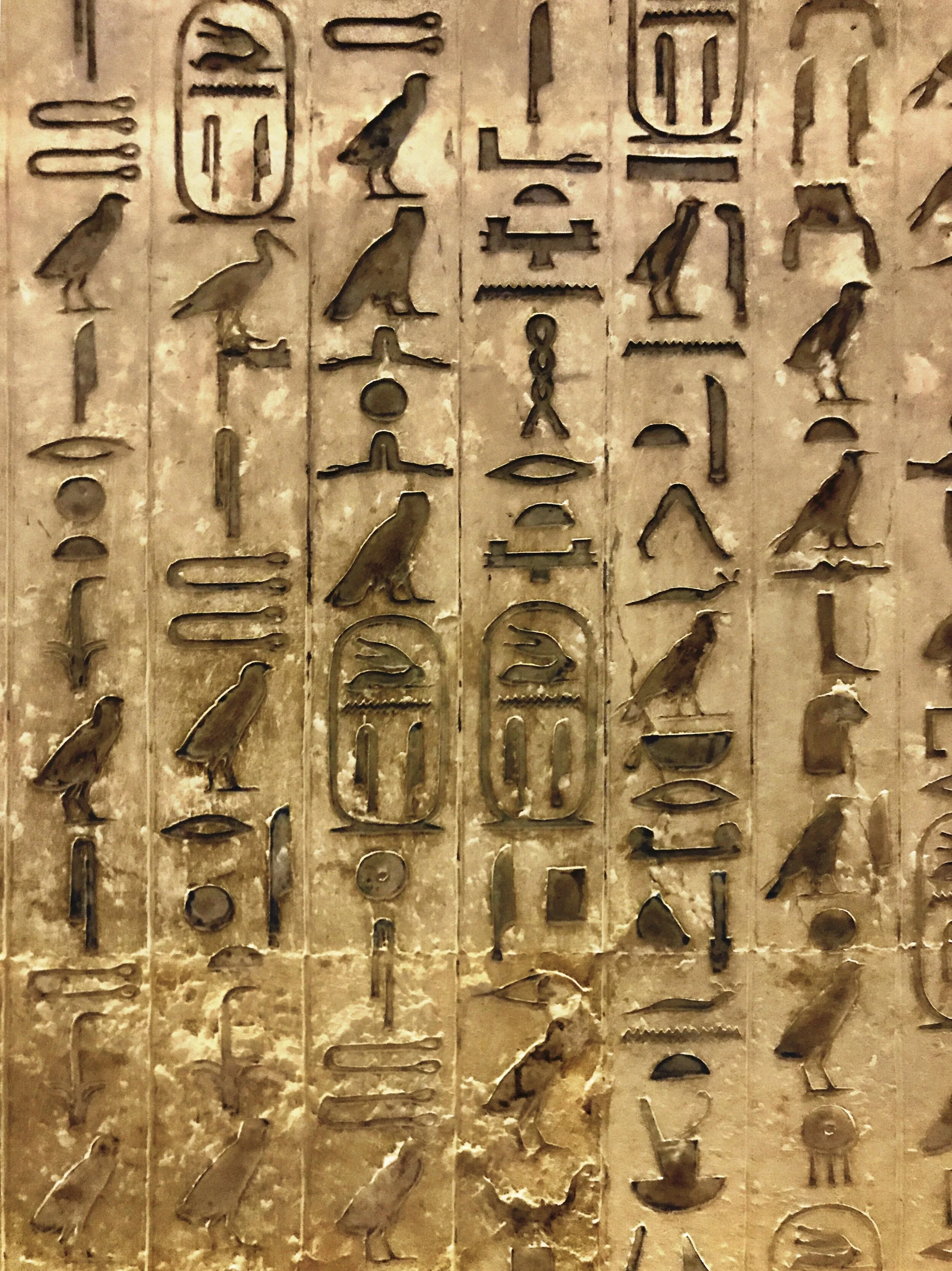

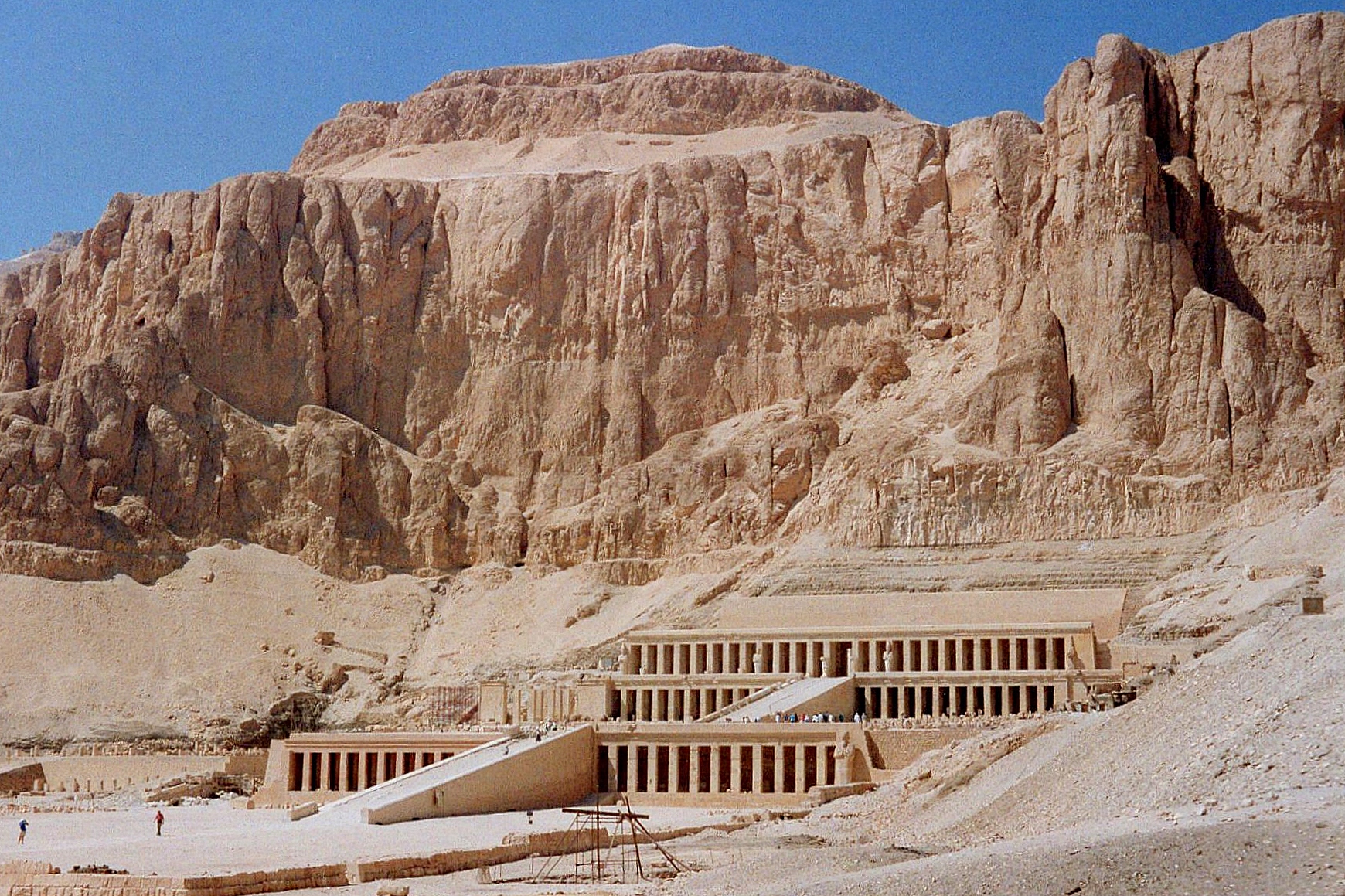

In general, the subterranean walls and passages of New Kingdom royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings were laid out in a succession of descending corridors and chambers adorned with texts and reliefs pertaining to the underworld. Over the centuries, thieves managed to raid all of tombs in this valley except one: KV62, that of Tut.

Although more modest in scale and lacking in decoration, Tutankhamun’s four-chambered tomb more than made up for that in content (though one has to wonder if the larger tombs, since plundered, held even more goods — we’ll never know.)

The narrow entrance corridor and minimal area of the tomb’s plan indicate that it had never been intended for the burial of a king. It’s been speculated that it was originally intended for Tutankhamun's vizier, Ay, or possibly the mysterious female pharaoh Neferneferuaten. Whatever the case may be, it was hurriedly adapted when he unexpectedly died in his late teens.

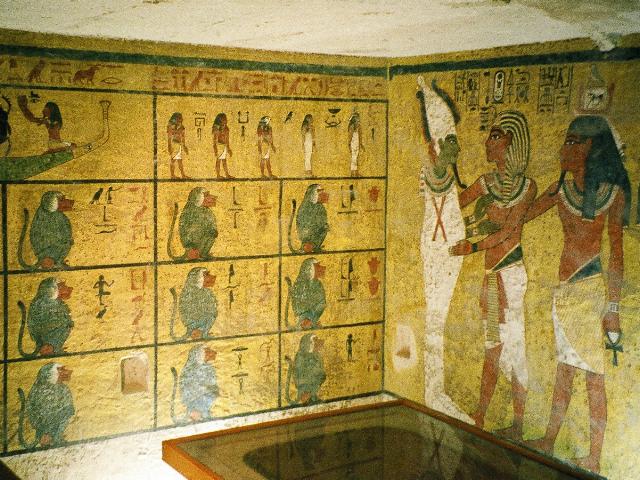

One of the few paintings in King Tut’s tomb shows his righthand man and successor Ay performing priestly duties to help the pharaoh journey through the afterlife

In Tut’s tomb, only one of the four small rooms, the burial chamber, is plastered and decorated with brightly painted scenes. The scene on the north wall depicts Tutankhamun in the form of Osiris, with his vizier and successor Ay, dressed as a high priest performing the opening of the mouth ceremony, meant to revive the dead pharaoh in the afterlife. A network of long-dead black mold spores like leopard spots perforate its surface, providing even more evidence of a rush job: The burial chamber was sealed before the paint even had time to dry.

Carter examines King Tut’s innermost sarcophagus

The Verdict

As far as Tut’s death goes, the jury’s still out — but it’s not as dramatic as some would like to imagine. He probably wasn’t assassinated, and he most likely couldn’t ride safely in a chariot. Tut comes from a long line of incestuous liaisons that severely weakened his immune system and left him with a diseased leg. Chances are this became infected and led to his untimely death. Tut, tut. –Duke