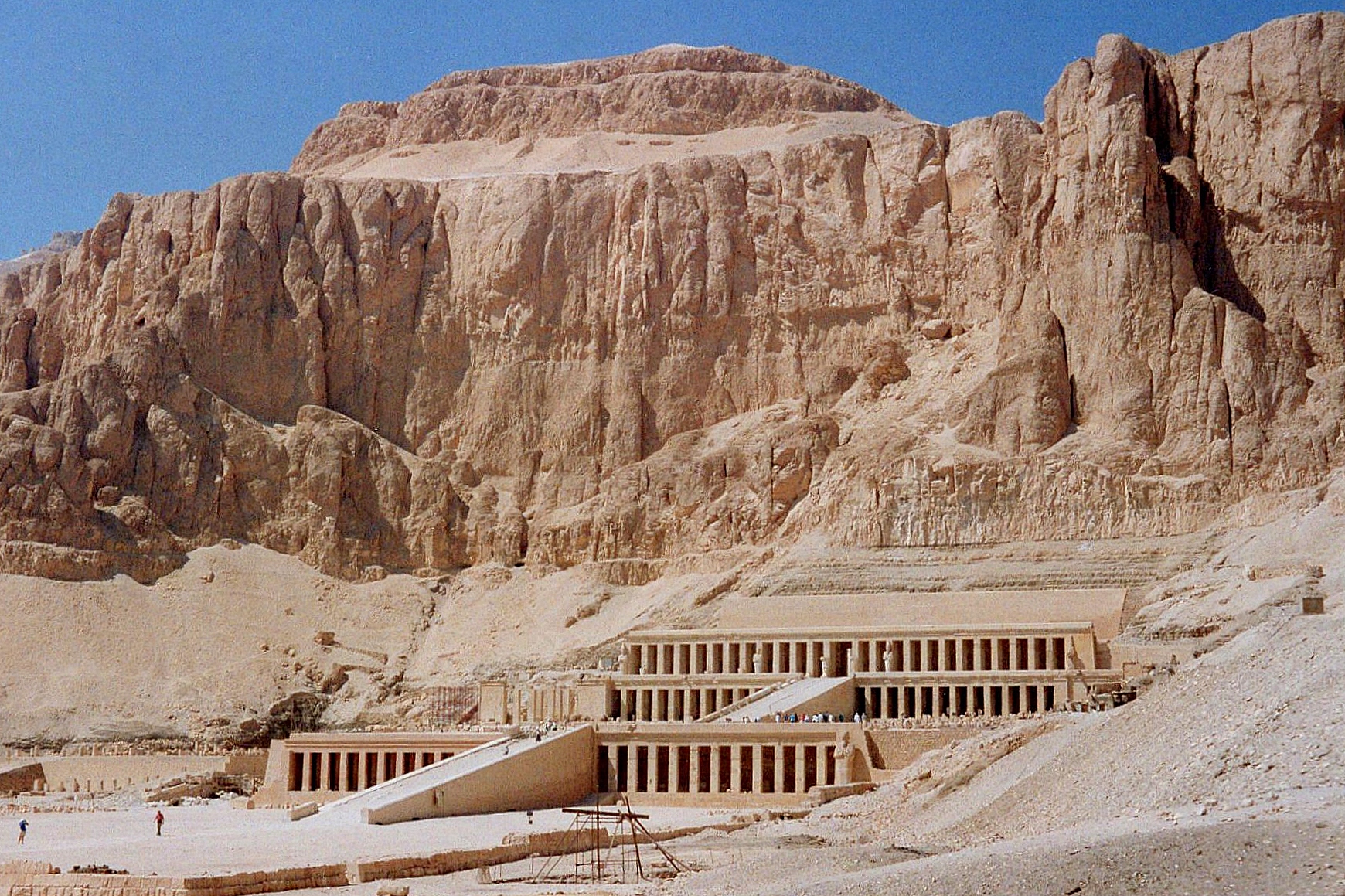

A firsthand account of what it was like to excavate the Hatshepsut temple at Deir el-Bahari in the 1970s.

Kenneth shares his experience as an archaeologist in Luxor, Egypt in the early 1970s.

Archaeology is one of those careers that sounds so thrilling — I always picture Harrison Ford as Indiana Jones on his search for the Ark of the Covenant (minus the snakes). But it turns out that, more often than not, this profession means long hours, low pay, and months or years of tedious fieldwork.

That being said, when Kenneth reached out to us with a kind note about our blog, mentioning that he had been briefly involved with the excavation of Hatshepsut’s temple at Deir el-Bahari, we simply had to learn more.

He obliged with an interview of what it was like to be an archaeologist in Egypt half a century ago, back when he was a starving field worker put up at the now-glamorous Winter Palace hotel, “in a shabby, Nile-view room with the bathroom far down the hall.” –Wally

The Colossi of Memnon stood as they do today, in a clearing surrounded by fields. But there were no barriers of any kind — you could climb the statues if agile enough.

What was it like being an archaeologist?

I was not a classical archaeologist for very long. (Not nearly as long as it took me to get my degree!) Turns out I liked to eat. And pay rent. Field work, which was really the reason I went into archaeology, pays next to nothing. There’s always a candidate working towards their doctorate who will offer to do the work for free.

In 1969, I worked in Winchester, England (the Roman capital of Britain) under the well-respected British archaeologist Martin Biddle and Birthe, his Danish-born archaeologist wife. It was Martin who got me a temporary position the next season with the joint British-Polish expedition working at Deir el-Bahari.

I was only at Luxor a few months before the Vietnam War intruded and I went off to the Navy. When I was discharged in 1973, the Arab-Israeli War was looming, and available funds for archaeological work in Egypt had completely dried up. I took what I thought would be a temporary job as a flight attendant, fell in love with the job and stayed 30 years. During that time, I met my husband, Michael (we celebrated our 35th anniversary last week), and the impracticality of going off on a months-long dig and leaving Michael at home put an end to any thoughts of returning to archaeology.

The top colonnade on Hatshepsut’s funerary temple — which did not exist in 1970 — is complete in this 1989 photo.

What was the project you were working on?

In 1970, restoration work was focusing on the third tier of Hatshepsut’s temple. The structure has been extensively rebuilt. Some Egyptologists would say overly rebuilt.

There was an ongoing search for stone blocks that had been appropriated by later pharaohs to use for their own building projects. In Upper Egypt there are vast areas filled with thousands of broken stone blocks from fallen or dismantled structures. Often, missing stones from a particular ancient monument can be discovered and moved (at great effort and expense) to their original site.

Kenneth’s husband, Michael, studying the statue of Horus at the temple at Edfu

Imagine you are working on a jigsaw puzzle. Some of the pieces are missing. In the next room someone has dumped into a huge pile thousands and thousands of pieces from hundreds of different jigsaw puzzles. In that pile you might find the missing pieces from your puzzle. The image on one of the pieces you are missing will be of a human arm. The left arm. And so as you sift through the huge pile of dumped puzzle pieces you are looking for one bearing the image of a left arm.

Of course, in Ancient Egypt when a stone was reused, it often had carving on one side. The stone would be turned so the carving was no longer visible, and a new carving would be done on a blank side of the stone block. Five hundred years later, the block might be reused again, and so there would be a third side that would be carved…

So, going back to that pile of jigsaw pieces, as you are looking for that image of a left arm, you’re having to turn each puzzle piece because there are different images on each side of each piece.

Fifty years ago, it was a laborious task to try to find a particular stone in one of many locations up and down the Nile. (Now, computers do the work in seconds.) There were huge books full of illustrations of thousands of “available” stones. One needed to just keep looking. And if — by chance — a stone with the left arm was found, arrangements had to be made to legally acquire and move a multi-ton block of granite or sandstone. Reams of paperwork were required. It was what we’d call grunt work. And that’s mostly what I did. No glamour. No glint of gold in the sand. It was pouring over books and filling out paperwork. But it was Egypt, and I loved it. (At Winchester I was actually on my hands and knees, excavating a burial ground filled with Roman soldiers. I found coins minted under the reign of Hadrian and carved-bone dice for gambling, and because of the high peat content of the soil, well-preserved leather sandals as well. Skeleton after skeleton too — some of the bodies pathetically shattered in battle.)

What’s your take on Hatshepsut?

Well, of course she’s a fascinating person. The oldest known woman on the planet. She jumps out at us, her carved thoughts in many instances perfectly preserved because Thutmose III covered them with a layer of stone: “Now my heart turns this way and that, as I think what the people will say. Those who see my monuments in years to come, and who shall speak of what I have done.”

I think that Hatshepsut, like Cleopatra Vll, 13 centuries later (and Joan of Arc, 1,400 years after that), must have dazzled through the sheer force of her personality, to have accomplished what she did. Usurping her stepson’s throne might have made sense if the lad was unwell or unfit for the job. But he went on to be one of Egypt’s greatest pharaohs! Was that despite Hatshepsut, or because of her?

Kenneth posing with Cleopatra and Caesarion on the rear wall of the temple complex at Dendera

When I worked in Egypt, there was only a slim hope that Hatshepsut’s body would ever be found. The fact that her architect (and supposed lover) Senemut’s red granite sarcophagus had been discovered broken into many pieces and spread across the desert seemed to indicate a royal temper tantrum that could very well have been Thutmose lll’s. Easy to imagine him hating the commoner whom Hatshepsut had showered with titles. I always thought that if Thutmose hated Senemut that much, he must have hated his ruling stepmother as well. The thought of ever finding her remains struck me as highly unlikely. I figured he eventually “grew a pair” and had her murdered and her body fed to the jackals.

But no! Now we know she was lying right under our noses in KV20 in the Valley of the Kings! And the proof that it was her right there in the Cairo Museum: one of Hatshepsut’s molars, packed in a small wooden box bearing her cartouche, and matching the gap in her mummified jaw. And we now know she grew old, and fat — with pendulous breasts. A life lived long!

So how and why was the throne eventually turned over to Thutmose? That is a mystery we may never unravel. I like to think Thutmose may have been a late bloomer. That his smart, capable stepmother watched over him and groomed him to become the great pharaoh he was.

The timeless Old Cataract, which Kenneth and Michael say is “one of our favorite hotels anywhere in the world.” Wally and Duke agree!

What was your favorite memory of that time in Egypt?

There were no tourists! War with Israel was looming. Luxor was virtually empty. Once, on a day off, I had Luxor Temple entirely to myself. Walking down a colonnade, between towering pillars, a falcon flew just over my head, sailing along ahead of me about 20 feet in the air. At the end of the colonnade, he rose up and landed on top of the head of an enormous statue — a statue of Horus. I just stood perfectly still, savoring the moment, and feeling I’d been visited by a god.

The floating restaurant Bodour, moored just upriver from the Winter Palace in Luxor, was one of their favorite places to dine, with its sumptuous Belle Epoque furnishings.

What was your least favorite memory of Egypt?

The food. I grew up in health-conscious San Francisco. I was desperate for salads, which were not safe anywhere in Egypt because produce was routinely fertilized with human excrement. I gave in to temptation on a quick trip to Cairo and ordered a chef’s salad at the Nile Hilton, the hotel in the city. (It’s now the Ritz-Carlton.) I thought, “Surely it will be safe to eat a salad here.” Nope. I ended up at Cairo’s American Hospital for two days!

The rising sun turns the Theban mountains pink. As you can see, the West Bank was entirely agricultural. Luxor had yet to jump the river.

How has Egypt changed since the 1970s?

As far as the monuments are concerned, 50 years is a mere blink of the eye. The ancient stones are unchanged. What has changed is contemporary Egypt. In 1970 the view across the Nile from the Winter Palace was one of cultivated fields and the distant Theban mountains. That was it. (I could just make out the ramps at Deir el-Bahari from my room’s balcony.) There were hardly any visible West Bank buildings at all. The few villages, such as sand-colored Qurna, blended in with the cliffs. These days, the city of Luxor has jumped the river and spread along the West Bank.