Akhenaten moved the capital from Thebes to an undeveloped stretch of land in the middle of the country. It didn’t last long.

Unlike the other monuments of Ancient Egypt that are well preserved, little remains of the short-lived capital of Amarna

Pharaoh Akhenaten, now disparaged as a heretic, made some bold decisions that completely uprooted thousands of years of Ancient Egyptian tradition, including the move to the worship of a single god. This brief era, lasting less than two decades, is known as the Amarna Period and took place in the 1300s BCE. Not surprisingly, all that remains of Akhenaten’s legacy are fragments here and there, some of which had been buried for thousands of years in the sand, some of which were torn apart and repurposed in construction projects elsewhere in the country — and some of which surely have yet to be discovered.

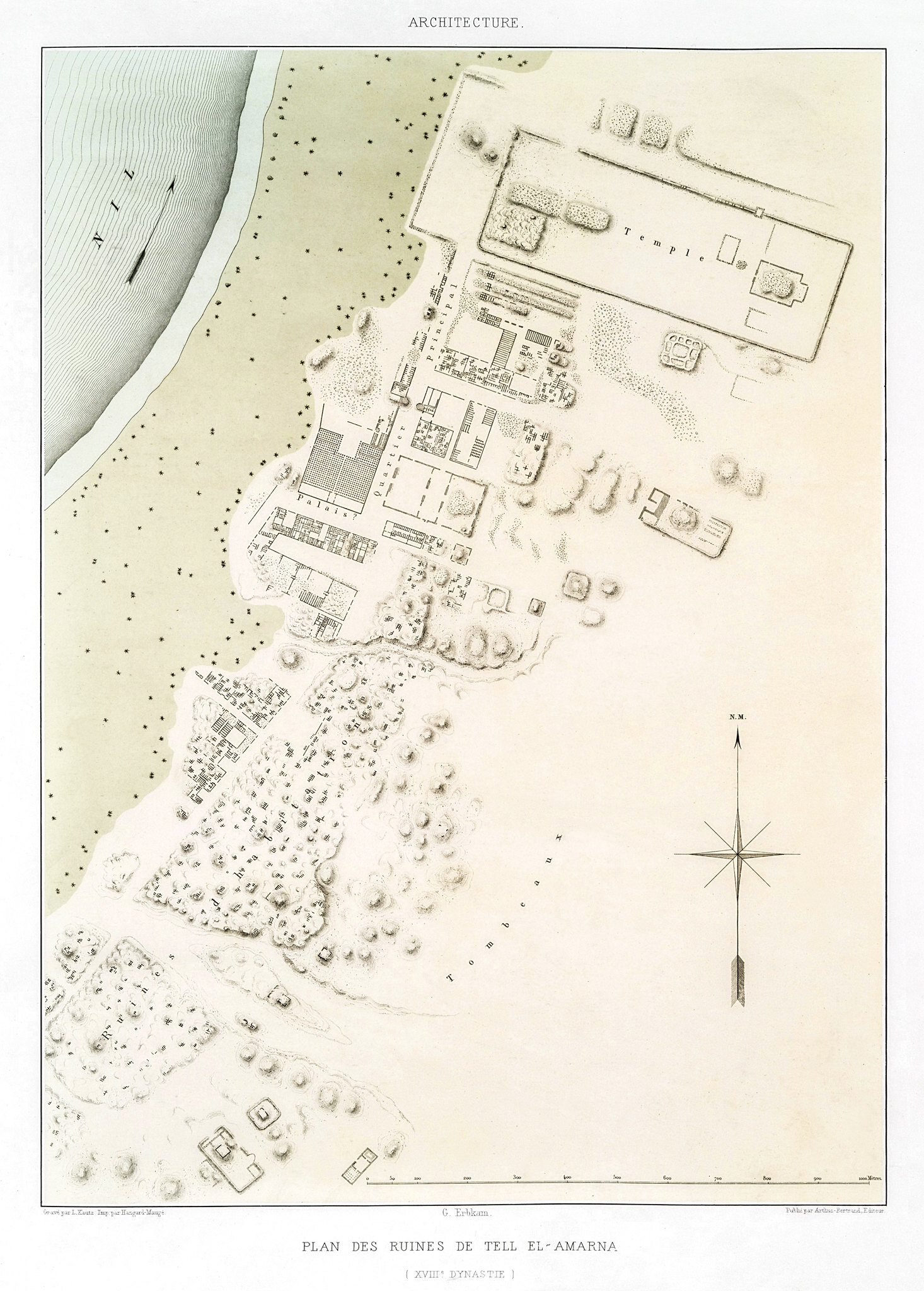

A map of Amarna, with a large temple to the Aten at the top

The Move to Amarna: The New Capital of Akhenaten

At this time, the cult of the chief deity, Amun, held great power, particularly in Thebes, modern-day Luxor, which had become the religious and political center of Egypt. Perhaps as an attempt to reduce the power of the Amun priesthood, Akhenaten (the name he adopted, as he was previously known as Amenhotep IV) decided to decree that all worship be shifted away from Amun and the rest of the pantheon to a minor sun god, the Aten. On top of that, he moved the capital to an unoccupied stretch of desert along the Nile, bordered to the east by cliff walls that would house the royal tombs. He named the new city Akhentaten (Horizon of the Aten), confusingly similar to his new name. The city is now referred to as Amarna. The site was located on a barren stretch of the desert that lay between Lower Egypt’s capital, Memphis (200 miles to the north), and Upper Egypt’s capital, Thebes (250 miles to the south), making it a good spot to administer both lands.

Why did Akhenaten make this drastic move? Despite the fact that many Egyptologists delight in thinking it was the doing of a religious maniac who decreed that the old gods were false and that only one deity, the sun, deservered reverence, it was “dictated less by theological insanity than by court intrigue and politics,” writes Nicholas Reeves in his book Akhenaten: Egypt’s False Prophet, republished in 2019.

When you declare that all of the old gods are forbidden but one, as Pharaoh Akhenaten did, you’re going to piss off a lot of people — especially the wealthy and powerful priesthood of Amun, the former chief deity

An Assassination Attempt?

Reeves, always one to lend credence to a conspiracy theory, hints that a brush with death could have led to the move. “If Akhenaten had narrowly escaped assassination — and his subsequent persecution of the Theban god does indeed suggest a grudge of considerable magnitude — then he was now moving cleverly and decisively to outflank the opposition.”

While the Amun priesthood certainly had their gripes with a sudden loss of power and wealth, Reeves suggests that the population, the younger ones in particular, viewed the move to a new capital as an exciting adventure, “a contrast to the staid and perhaps stale atmosphere of conservative Thebes,” he writes. “For the new generation, pharaoh was the hero of the hour, the man who had re-established true order on the Egyptian world. There was energy in the air; the people believed.”

All that remains of the once-impressive north palace of Amarna

Akhentaten: Nearly a Decade in the Making

It was nine years before Akhentaten celebrated its official inauguration — “and to judge from the number of wine-jar dockets of this date recovered from the site, it must have been quite a party,” Reeves writes.

Although Akhenaten wasn’t known for his economic aptitude, he started out with overflowing coffers. Much of the wealth of his new capital came from the pilfered stockpiles of the old gods, Amun in particular.

Akhenaten and his family can be seen worshipping the Aten (aka the sun) in a tomb carved into the cliffs outside of Amarna in this photo from 1903

Amarna art focused on nature, reflecting the lush oasis Akhenaten created

Today Amarna is a desert wasteland, so it’s difficult to imagine that it once was a lush, green oasis, filled with trees and bushes, as depicted in the reliefs of the time. One of the highlights of the city were its gorgeously painted pavements showing scenes of nature. They were uncovered by the archeologist Flinders Petrie (amusingly described by Reeves as “legendary but dour”) in 1891. Petrie took great pains to preserve these works of art — but a local farmer destroyed most of them in a fit.

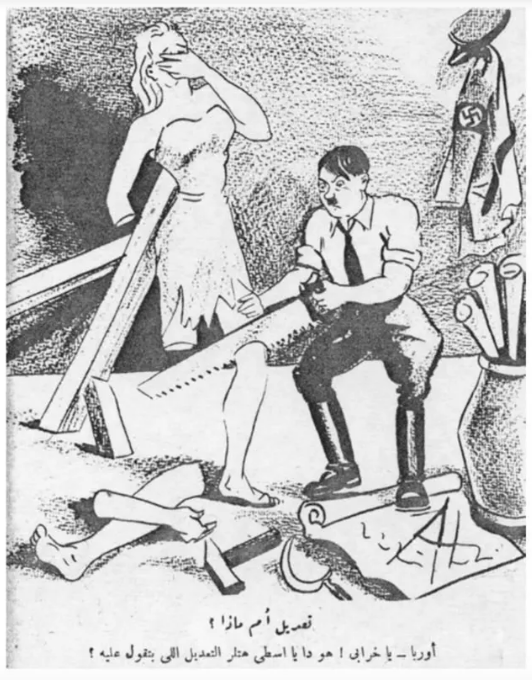

Even Hitler fell under the spell of the beautiful Nefertiti, as depicted in her famous bust

Hitler and the Famous Bust of Nefertiti

The palace and major temple were located in the north, so it’s interesting that many of the higher-end villas, like that of the vizier (a role we might now call prime minister), were built in the south — as far as possible from the pharaoh to still be within the boundaries of Akhentaten.

It was in one of these villas, owned by the artist Thutmose, whose house doubled as his studio, that the famed one-eyed bust of Nefertiti was found. If you want to see it in real life, you’ll have to visit the Berlin Museum. There was talk that the sculpture would be returned to Egypt during World War II, but Hitler liked Nefertiti’s “Aryan” appearance, declaring, “What the German people have, they keep!”

If you want to see the bust of Nefertiti, you’ll have to go to Berlin, as these visitors from 1963 did

A political cartoon in an Egyptian newsweekly from 1940: The woman, who represents Europe, is shouting, “Oh, no! Hitler, is this the new order you preached about?!”

This statue of Nefertiti was a particular favorite of Adolf Hitler’s, and for four years had been kept inside a fortified anti-aircraft gun tower next to the Berlin Zoo.

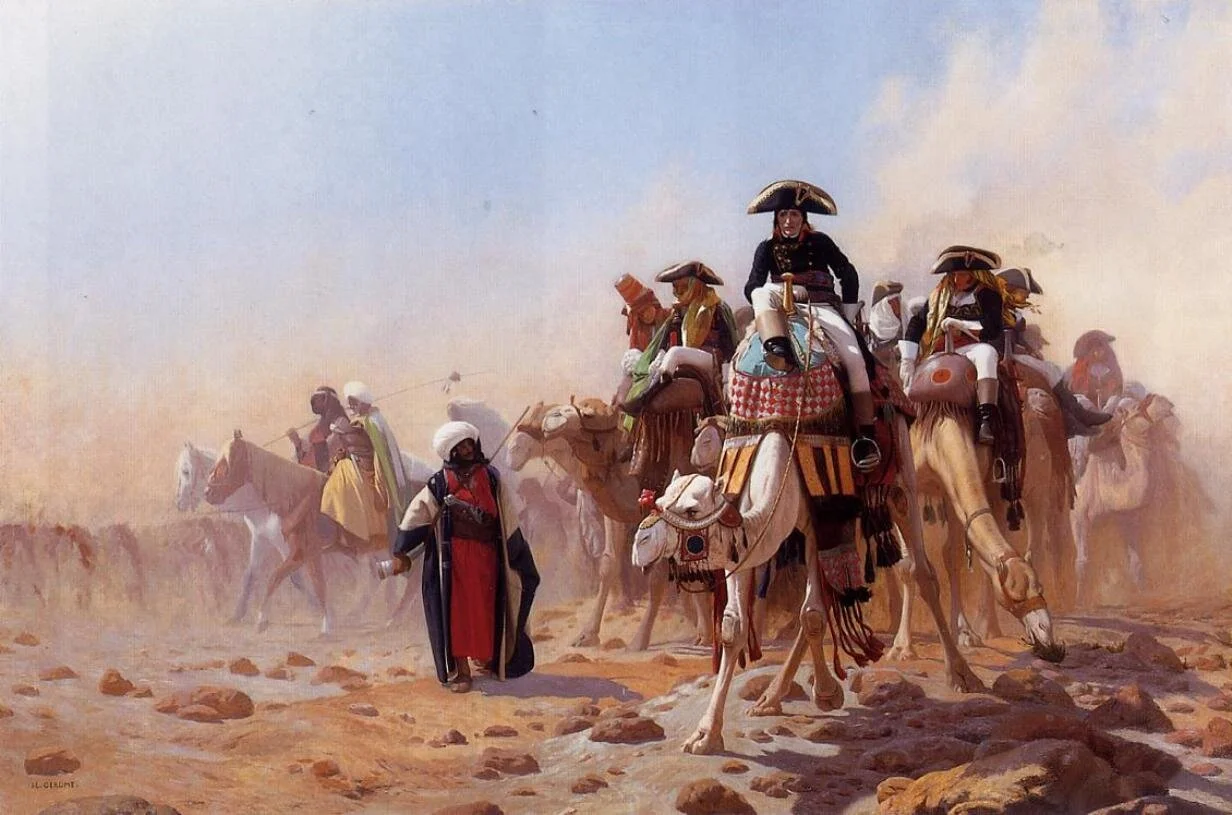

Napoleon During His Campaign in Egypt by Jean-Léon Gérôme, 1863

Napoleon and Amarna

Amarna remained undiscovered for so long in great part because the local population, “whose habit of shooting first and greeting later deterred the curious from taking an interest in the area,” according to Reeves.

The first Westerners to lay eyes on Amarna were members of Napoleon Bonaparte’s expedition of 1789-1799. The French had come in search of a new passage to India. On all French ventures at the time, scholars were brought along to study and record the culture and history of the lands they passed through, and this was no exception. In fact, Napoleon had 139 of these “savants” in his party.

Very little remains of Amarna today — most buildings were used in other construction projects or simply abandoned

All’s Well That Ends Poorly

The new capital was, ultimately, a failed experiment. It only lasted 17 years. There’s no record of how or when Akhenaten died, but Reeves, of course, wouldn’t be surprised if he was the victim of foul play.

Whatever the cause, the Egyptian people weren’t too bummed at the city’s (or pharaoh’s) demise. As Reeves writes:

For ordinary folk, there is little doubt that Akhenaten’s actions as king over time inflicted the greatest misery: the people were confused by the man’s religious vision, frightened by the ruthless manner in which it was imposed, and quite likely appalled by his personal behaviour. Denied the celebration of the traditional religious festivals which gave form to their year, and brought to the very verge of bankruptcy by their king’s over-ambitious schemes and administrative incompetence, disillusionment was clearly widespread.

Akhenaten’s successor, none other than Tutankhamun, moved the capital back to Thebes, and reverted to polytheism — changing the end of his name from -aten to -amun to signify an allegiance with the previous chief deity, Amun.

History hasn’t looked favorably upon Akhenaten, a pharaoh whose drastic actions and lack of acumen in ruling nearly ran the legendary empire into the ground. –Wally