The oldest church in Málaga has a Picasso connection and is home to legendary Holy Week statuary, including El Rico, who pardons prisoners, and El Cristo de Medinaceli, who grants wishes.

This figure depicts the Immaculate Conception of Mary. She stands atop a crescent moon and the world. Her left foot crushes a serpent, symbolizing the original sin assigned to all humans since Adam and Eve—except, of course, to the pure Virgin.

You could easily walk past the exterior of the Parroquia de Santiago Apóstol without realizing the wonders that lie within. The church, which is dedicated to Saint James the Apostle, is located on Calle Granada and was under restoration when Wally and I visited our friends Jo and José in Málaga, Spain in 2015. We strolled by it multiple times, completely unaware of its spectacular interior and ended up buying a few whimsical wire and black glass marble ants from a street artist who had set up shop on a mat across from it.

The church’s wooden doors feature vieras, or scallop shells, the symbol of Saint James.

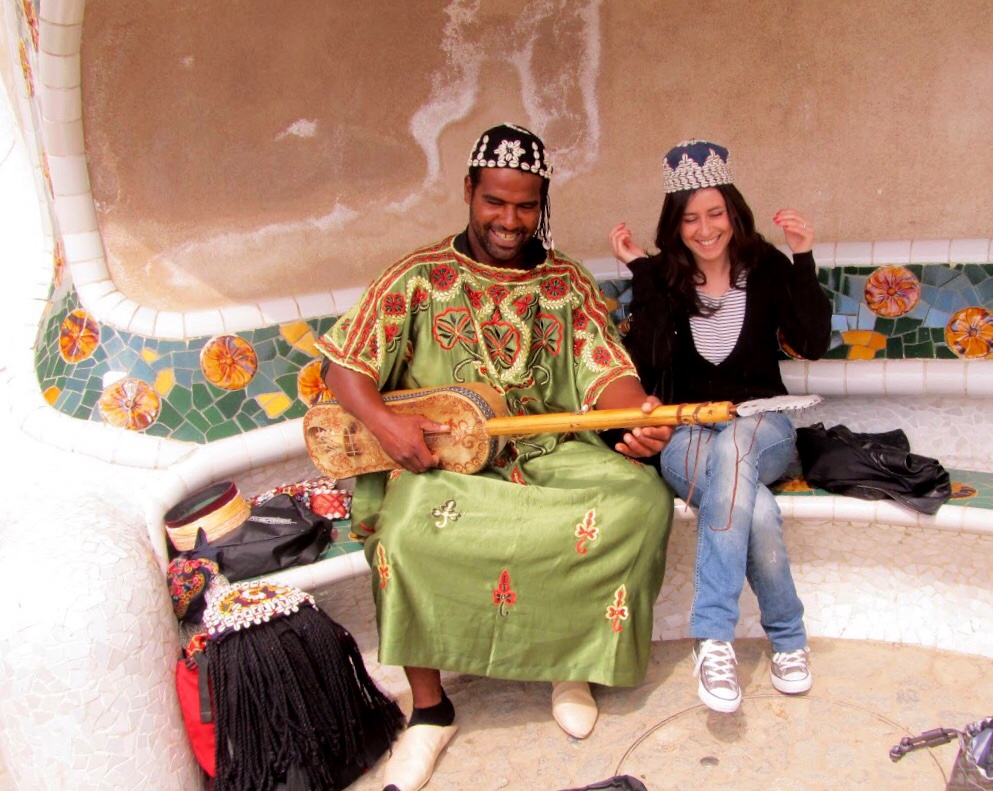

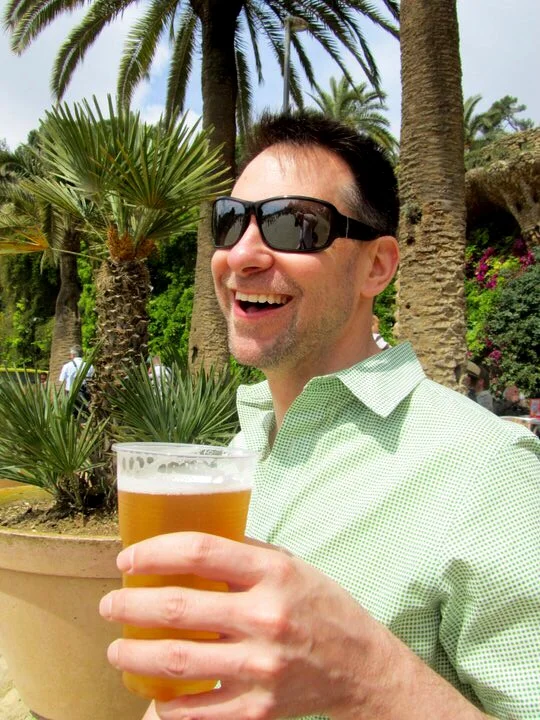

Eight years later, we were back in Spain, and Jo and José suggested adding it to our itinerary. We’re fortunate to know some locals, and we’re never disappointed by what they share with us. Plus, Wally and I love visiting old Catholic churches. These places are not just architecturally stunning; they’re usually brimming with vivid devotional art. And it goes without saying that Spain takes this to a whole other level.

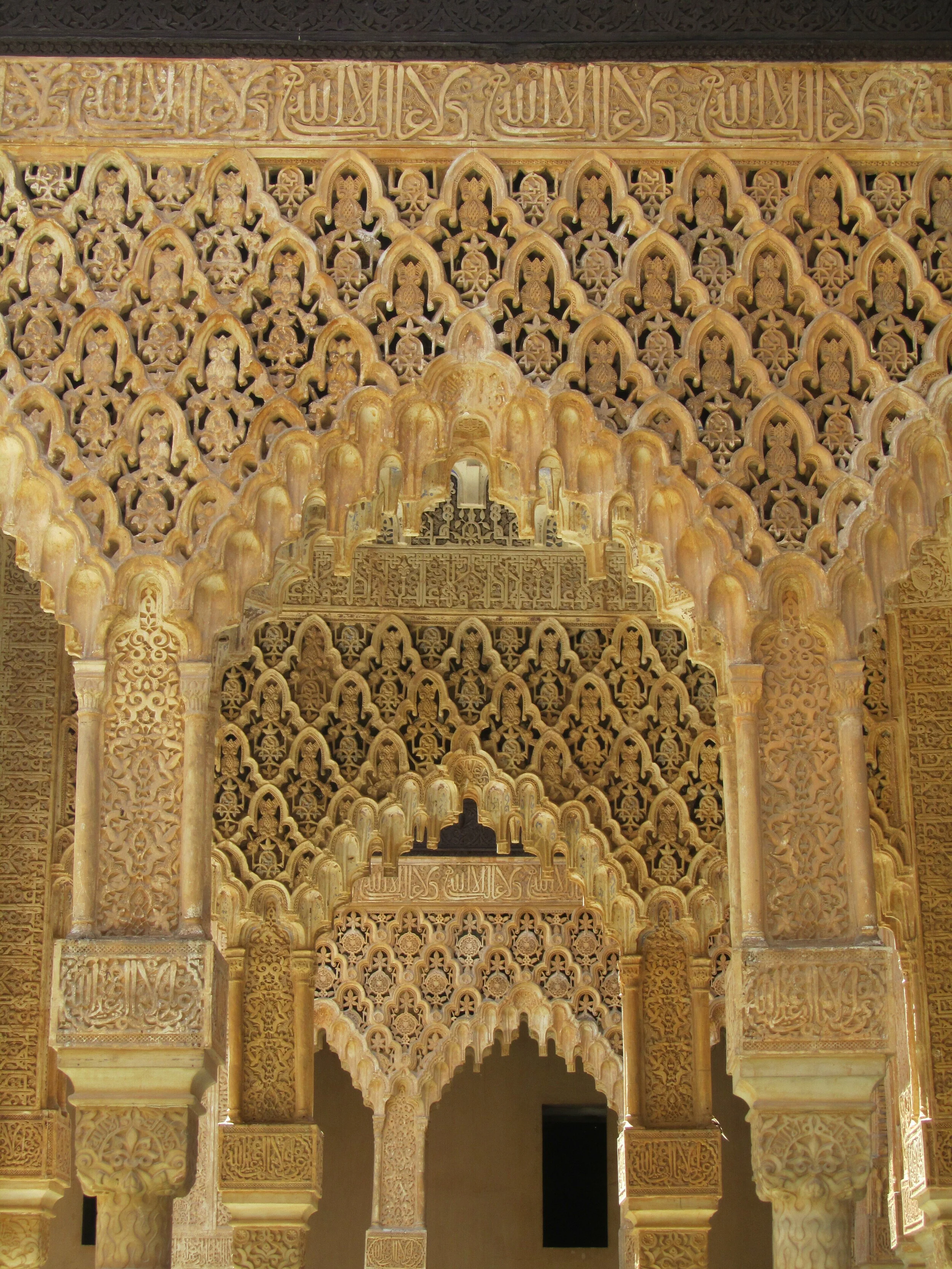

The pointed brick arch of the central doorway framed by tiles arranged in a geometric pattern is all that remains of the former mosque.

From Mosque to Gothic Church

After digging around a bit, I found out that this particular church was the first and oldest of the four parishes commissioned in Málaga by the Catholic Monarchs, Isabella and Ferdinand II. In fact, it dates back to 1509. The structure fuses Isabelline Gothic (a late Gothic/early Renaissance style) with Mudéjar elements and was established on the site of a mosque during the early stages of the city’s Christian conquest. Remnants of the former mosque were incorporated and are visible in the façade, particularly in the central doorway, where a pointed ogee arch is framed by tiles arranged in a geometric pattern that reads as floral. This arch would later evolve into the distinctive Gothic rib vault. In keeping with Islamic tradition, a minaret was built adjacent to the mosque, which was converted into the church’s bell tower during the late 16th century.

A view of the ornate central nave, dome and altar. The carved central altarpiece holds a likeness of the church’s patron, Santiago Apóstol aka Saint James.

the Interior of the Church of Santiago

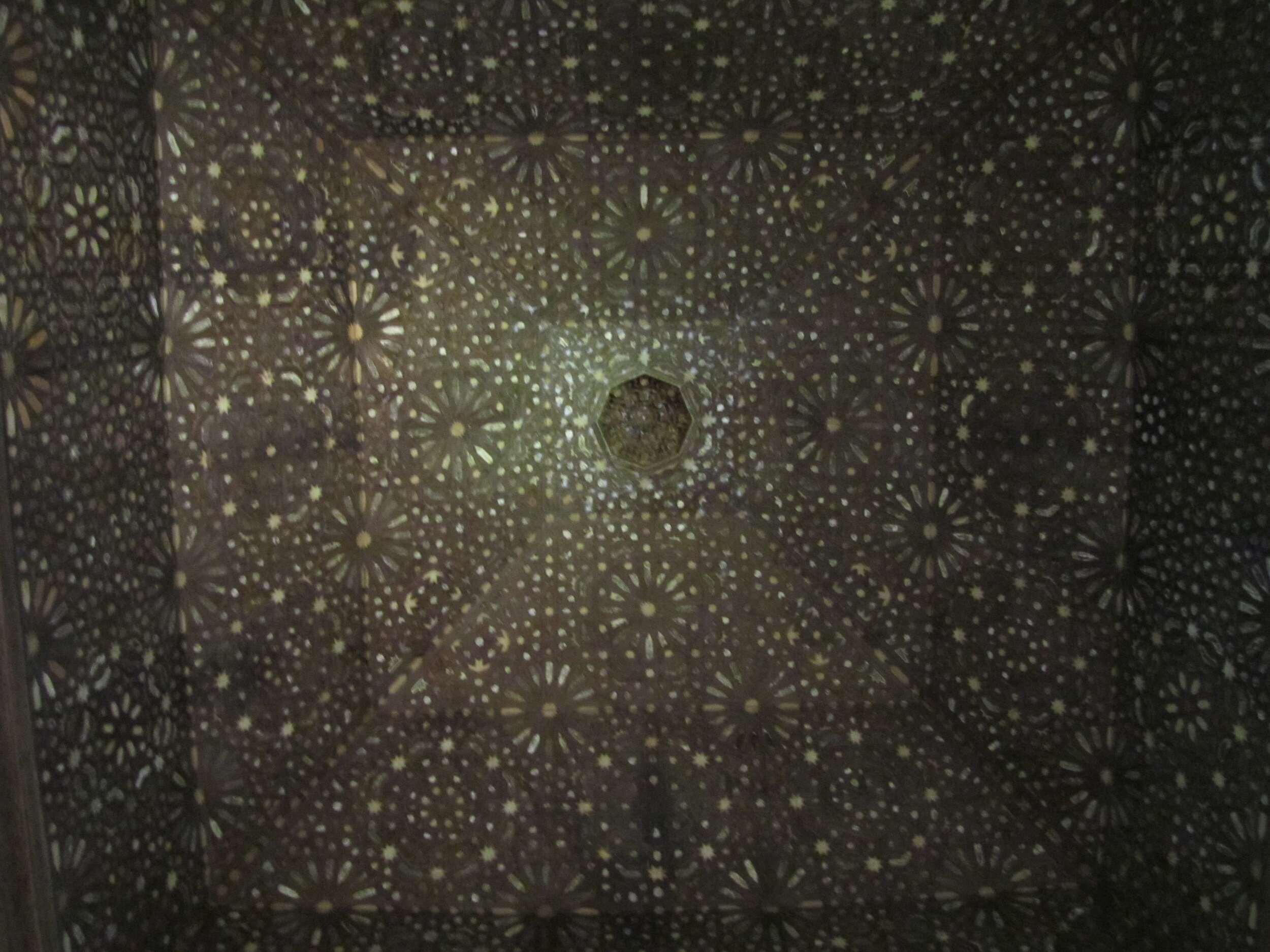

Inside, the Gothic style reveals itself in the vaulted ceilings and chancel of the central nave, which comprises the sanctuary, altar, choir and main chapel. The late 18th century saw the addition of two more naves, embellished in the Baroque style. The handsomely carved altarpiece is fashioned from polychromed (painted in many colors) and gilded wood, and the central niche holds a realistic statue of its patron saint, Santiago Apóstol (Saint James).

A depiction of Mary as the Queen of Heaven

Legend has it that following the death of Christ, James traveled to Galicia in northern Spain to spread the word of Christianity. However, things took a dark turn upon his return to Jerusalem — he was beheaded under King Herod’s order, becoming the first disciple to be martyred.

Fun fact: Pablo Picasso was christened in this church on November 10, 1881, and his baptismal certificate is kept here. Although his family moved to A Coruña in the Galicia region of northwest Spain when the artist was 9 years old, he always considered himself a malagueño, that is, someone from Málaga.

This diminutive likeness of the Virgin Mary, Nuestra Señora del Pilar (Our Lady of the Pillar), stands atop a small column. You can’t see it because it’s covered by the red and gold mantle.

A Tour of the Art and Semana Santa Statues of Parroquia de Santiago Apóstol

Among the significant religious artworks that can be found in the church’s naves is the Virgen de las Animas (Virgin and the Souls) by Juan Niño de Guevara, a large oil painting depicting the Mary comforting souls condemned to Purgatory. According to popular tradition, the faithful offer prayers to the image and leave bottles filled with lamp oil to keep the flames of the glass votives burning in perpetuity for the souls doing penance before being able to enter the kingdom of Heaven.

Additionally, the statues of the Cofradía del Rico and Hermandad de la Sentencia religious brotherhoods are kept inside this church year-round, except during Semana Santa (Holy Week). That’s when they’re placed on massive tronos, quite literally thrones, weighing up to 2 tons and are carried through the streets of Málaga by penitents and members of their religious fraternity.

This nave holds the processional images of Jesús de la Sentencia (Jesus of the Judgement), María Santísima del Amor Doloroso (Holy Mary of Sorrowful Love) and San Juan Evangelista (Saint John the Evangelist) which belong to the religious brotherhood of the Hermandad de la Sentencia.

There are the venerated mannequin-like processional figures of María Santísima del Amor Doloroso (Holy Mary of Sorrowful Love) and Jesús El Rico (Jesus the Rich). To impart a heightened sense of realism, glass was used for the eyes, hair for the eyelashes and ivory for the teeth.

Jesús El Rico (Jesus the Rich) hides behind María Santísima del Amor Doloroso (Holy Mary of Sorrowful Love), which belong to the brotherhood of the Cofradía del Rico. El Rico pardons one prisoner each year.

The Ultimate Get Out of Jail Free Card

El Rico has extended pardons as an act of grace every Holy Wednesday, a tradition that traces its roots back to 1759. The practice of extending a second chance to a prisoner originated during the plague epidemic that swept across Europe during the reign of Carlos III.

It’s said that a riot erupted after inmates learned that Holy Week processions would be canceled due to contagion fears. In response to the news, prisoners mutinied, broke out of jail and carried the life-sized statue of Jesus through the streets of Málaga, praying for salvation from the plague. Rather than fleeing afterward, they chose to return to prison. Impressed by their act of piety, the king decided to grant the Cofradía del Rico brotherhood, the guardians of El Rico, the right to release one prisoner every year. To this day, El Rico symbolically performs this act.

Make a Wish Foundation

If these treasures in this historic church aren’t enough to pique your interest, there’s one more notable devotional figure worth mentioning within the Iglesia de Santiago Apóstol: El Cristo de Medinaceli (Christ of Medinaceli). It received its name because the original was owned by the Duke of Medinaceli.

Every first Friday of March, devotees queue up outside the parish doors and wait their turn to kiss the statue’s feet. They also place three coins — they have to be of the same value — at his feet and make three different wishes. Be careful, though: Only one of your wishes will come true.

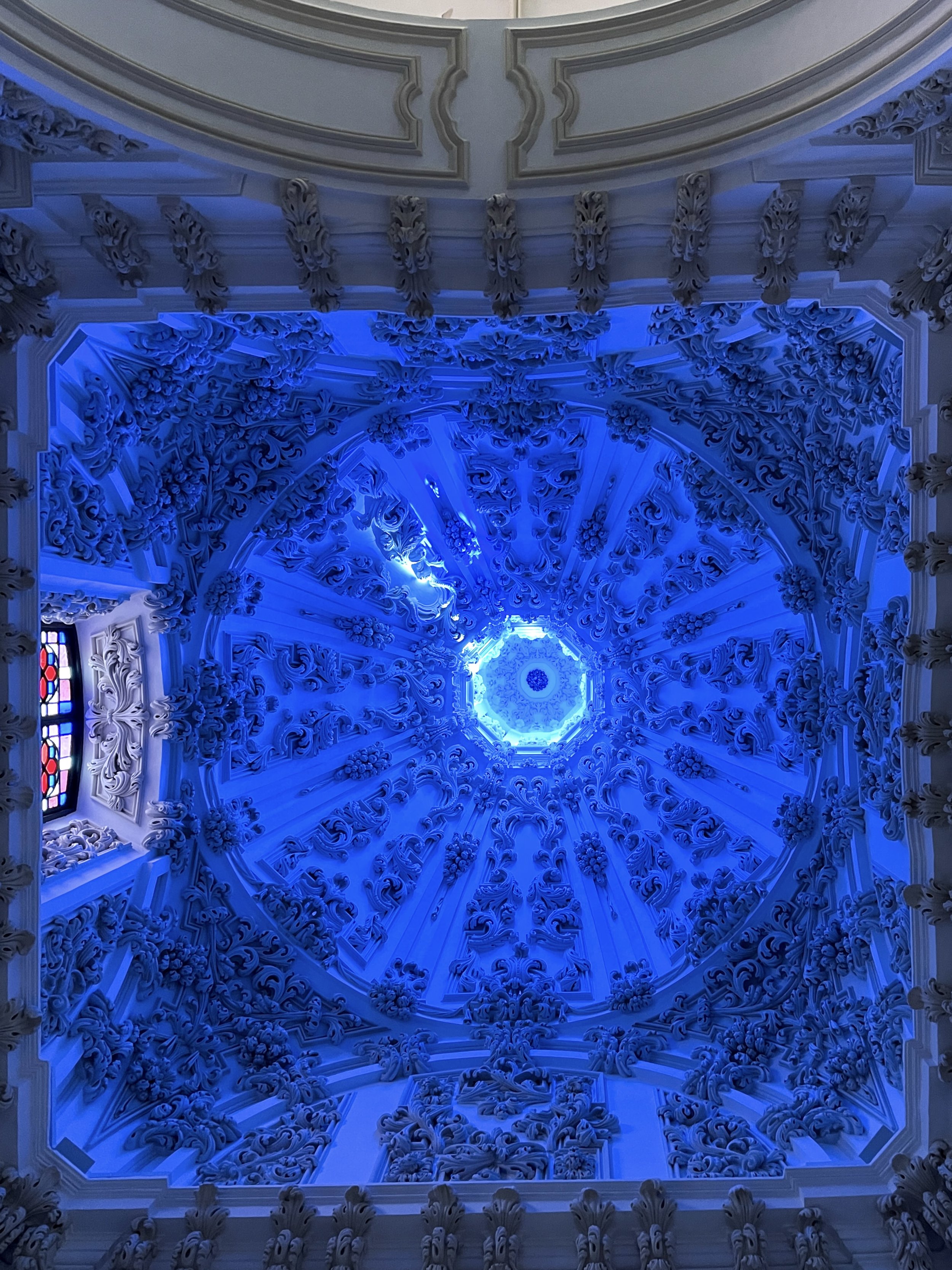

One of the most dramatic aspects of the Iglesia de Santiago Apóstol (and that’s saying something!) is the blue hue of this elaborate dome.

This relief depicts a crowded take on the Last Supper.

If you’re in the neighborhood, and you don’t stop by and admire the Semana Santa statues here, you’ll wish you had. –Duke

Iglesia de Santiago

Calle Granada, 78

29015 Málaga

España