The surprising origins of Jolly Old St. Nick include a tie to prostitution, kids chopped into pieces, a devil named Krampus and a racist tradition around his helper Zwarte Pieter, or Black Peter.

Our beloved Santa Claus started out as a bishop from Asia Minor named Nikolaos

Growing up, I can vividly remember nearly peeing my pants when I was 6 years old. It was early Christmas morning and I was afraid that if I left my room I would startle Santa and he wouldn't leave me any gifts. The willpower of a child is strong, but the pull of a tree with gifts beneath it stronger.

Fast forward to the sad rite of passage in learning that this being you believed in was a lie. Maybe you discovered your parents’ hiding place for gifts (my dad’s office) before they put them under the tree, or perhaps a friend told you.

“A butcher welcomed three children into his shop, slayed them and unceremoniously tossed them into a tub of brine to cure, with the intent to sell their flesh as ham.”

What most of us don’t know is that the inspiration for Santa Claus came from a real man whose historic generosity would become a legacy for the ages.

11 Little-Known Facts About St. Nick

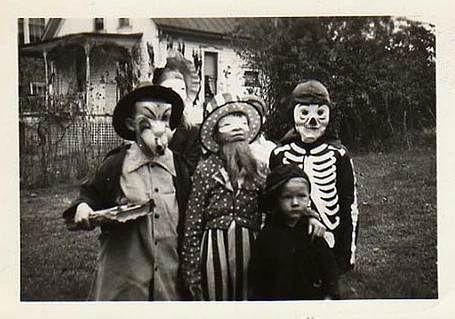

A children’s book about Sinterklaas, the bishop who became Santa Claus

1. He didn’t live at the North Pole.

Far from his home and workshop at the top of the world, in the south of present-day Turkey, lived a 4th century bishop whose full name was Nikolaos of Myra, a city now known as Demre. An ancient Byzantine church dedicated to St. Nicholas and containing his tomb still stands in Demre. Legend holds that it was built on the foundation of a Lycian Temple of Apollo.

St. Nicholas came into money at a young age, and was always very generous with it

2. Saint Nicholas was born into a wealthy family — and had a penchant for charity.

Born a rich man’s son, Nikolaos donated his inheritance to the poor by giving them gifts, which he’d toss through open windows. Details changed as the story was retold with later iterations of him having tossed them down chimneys — the vehicle for Santa Claus to enter homes.

3. The tradition of putting out stockings was to protect young maidens from being sold into sex-slavery.

Many stories are told of his generosity, such as the tale of the father and his three daughters. To save the maidens from being sold into prostitution for want of dowries, Nikolaos tossed a bag full of gold into the man’s house. It landed in one of the stockings the eldest daughter had hung up to dry. Now she could be married and was spared from selling her body to survive. The other two daughters quickly hung up stockings for Nikolaos to fill with gold, so that they, too, could be married.

Note the bags of gold, which saved three young women from a life of prostitution, in this depiction of a young, hot St. Nick

(As an interesting aside, the three golden globes that have come to symbolize a pawn shop are attributed to these three purses of gold.)

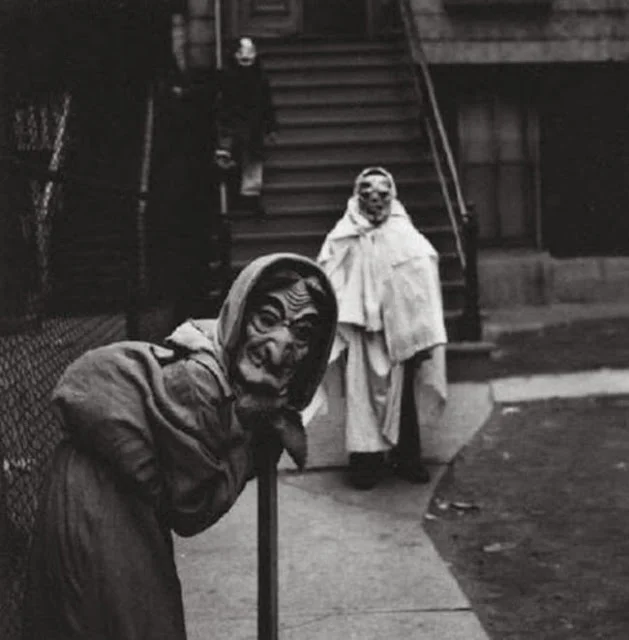

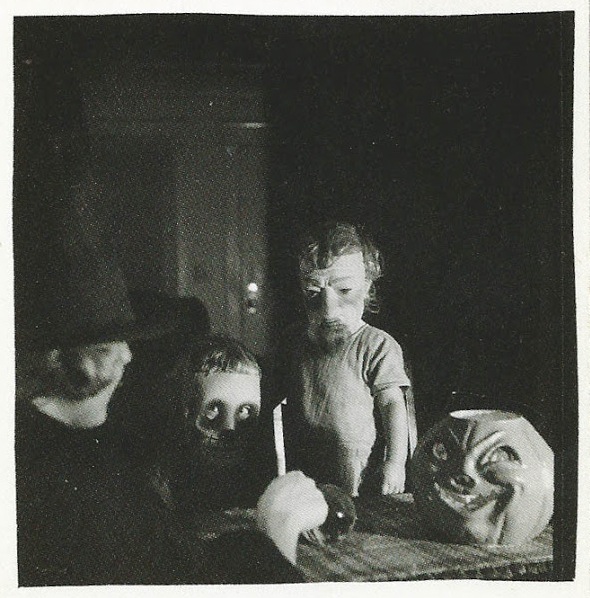

Yeah, it’s kind of creepy that Saint Nicholas comes while kids are sleeping — but, hey, they get some toys out of it

4. Stockings shifted to shoes after Nicholas’ death.

The Feast Day for Saint Nicholas is celebrated annually on December 6, the anniversary of his death. This led to the custom of children hanging stockings or, later, placing their shoes out with carrots and hay for the saint’s horse, hoping that Saint Nicholas would fill them with fruit, candy and other small gifts.

5. Early iconography depicts him as a white-haired bishop atop a horse.

Known as Sinterklaas in the Netherlands, he is a stately and resolute man with long white hair and a full beard. He wears a lengthy red cape over a traditional white bishop’s alb, or tunic, holds a long ceremonial shepherd’s staff with a fancy curled top and rides a majestic white horse.

Saint Nicholas resurrected three kids who had been chopped into pieces by a butcher and left in a salted tub to be passed off as cured ham

6. A not-so-pretty ditty tells of the murder of children and Saint Nicholas’ role in their resurrection.

A 16th century French song titled “Le Légende de Saint Nicholas” recounts the unfortunate and gruesome fate of three children.

The song, inspired by a miracle performed by Saint Nicholas tells of a butcher, who during a time of famine, welcomed three children into his shop, slayed them and unceremoniously tossed them into a tub of brine to cure, with the intent to sell their flesh as ham. Saint Nicholas, visiting the region to care for the hungry seven years later, not only saw through the butcher’s horrific crime but also miraculously resurrected the three boys.

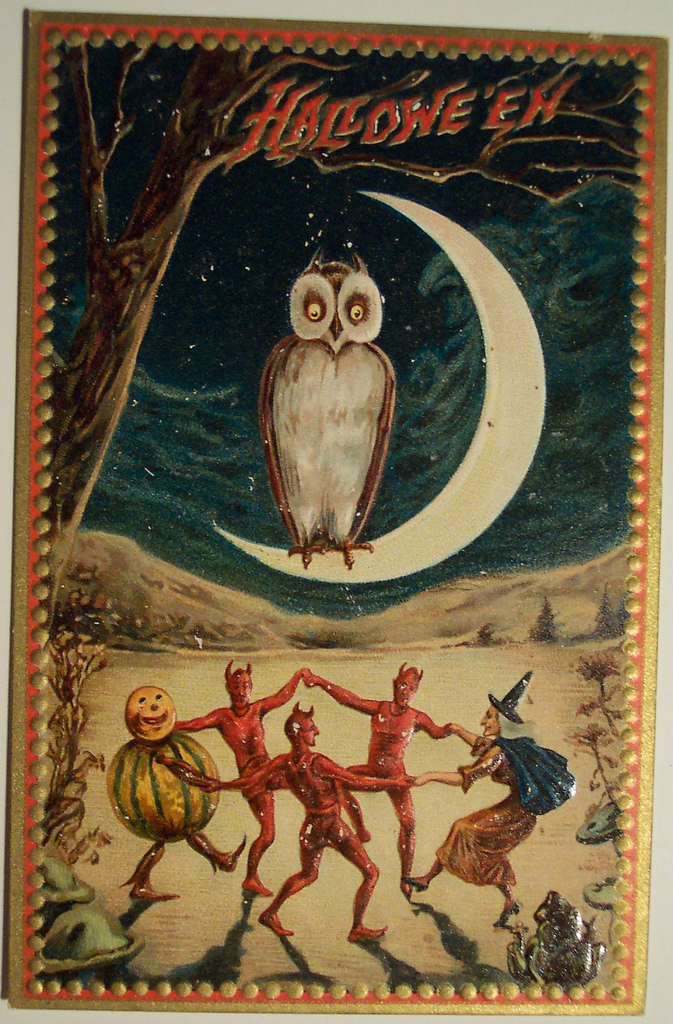

If you’ve been good, St. Nicholas will bring you gifts. If you’ve been naughty, you’re screwed

7. He hangs out with a devil, so be good for goodness’ sake!

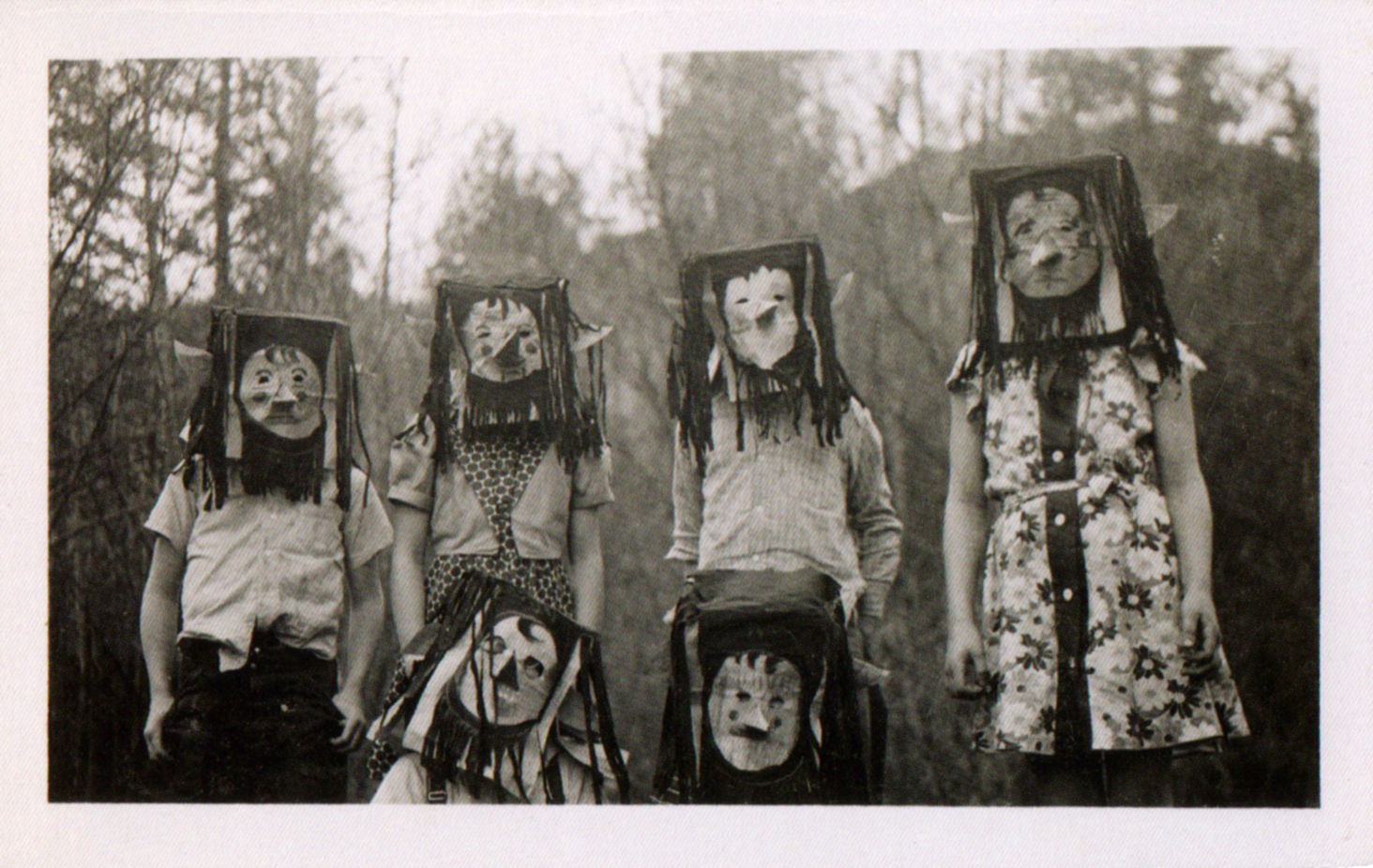

Saint Nicholas was occasionally portrayed in medieval iconography taming a chained devil, who would later become the cloven-hoofed half-goat, half-demon Krampus. Children who have behaved get gifts from Saint Nicholas. Those who have not suffer a terrible fate: They get beaten with a birch switch by Krampus and are packed away in his bag to be taken to Hell.

8. Saint Nicholas’ helper wasn’t an elf — it was a slave.

In Holland, Sinterklaas doesn’t have elves helping him deliver gifts. He has the arguably racist companion Zwarte Pieter (Black Peter).

To this day, parade participants don blackface, red lips, nappy wigs and colorful period attire.

Saint Nicholas’ helper is Black Peter, a controversial character that inspires people in the Netherlands to actually think it’s OK to wear blackface around the holidays. Illustration from a book by Rie Cramer

By Dutch tradition, Zwarte Piet was the servant of Sinterklaas — most likely a “blackamoor,” the name given to Africans who were captured and sold into slavery. The Dutch had the preeminent slave trade in Europe, and one of their roles was acquiring and transporting slaves to the Americas. Slave trade was abolished in the Netherlands in 1863, and while some locals perceive wearing blackface and dressing up like Black Peter as an innocuous tradition, others view the practice as a distasteful connection to the past.

Eventually Saint Nicholas morphed into Santa Claus

9. He morphed into Santa Claus in the U.S.

The Reformation attempted to erase the image of St. Nicholas, without success. The tradition was brought to New Amsterdam, the original name for New York, established at the southern tip of Manhattan island, via Dutch settlers as the beloved and saintly bishop Sinterklaas. After years of mispronunciation, the name evolved into Santa Claus.

St. Nick lost much of his bishop’s attire and began wearing red cloaks before he got his telltale suit

10. Washington Irving played a part in our conception of Santa as well.

In 1809, author Washington Irving’s satire History of New York From the Beginning of the World to the End of the Dutch Dynasty, he introduced the “Knickerbocker,” a New Yorker who could trace his ancestry to the original Dutch settlers. It was also a reference to the style of pants the settlers wore.

In its pages, Irving described Santa as a jolly Dutchman who smoked a long-stemmed clay pipe and wore baggy breeches and a broad-brimmed hat. The familiar phrase “laying his finger beside his nose” first appeared in this story.

Naughty Santa! I guess people started leaving out milk and cookies so he wouldn’t drink their Cokes and eat their leftovers, as seen in this vintage ad

11. Things really do go better with Coke.

In 1822, Clement C. Moore wrote a whimsical poem for his children, “A Visit From St. Nicholas,” which was published the following year and is more commonly known by its opening line “’Twas the Night Before Christmas.”

Coca-Cola commissioned artist Haddon Sundblom to create an image of a wholesome, realistic Santa Claus, which was inspired by Moore’s poem. His popular image of a pleasantly plump Santa debuted in 1931 and is the one that endures, setting the standard for renditions that followed. –Duke