A biblical tale of nudity, curses and divine justice, the story of Noah’s son and the curse on Canaan raises more questions than answers. What really happened in that tent?

Ham saw his father naked and told his brothers, who rushed to cover up Noah.

The story of Ham isn’t as well known as, say, the Creation or the Garden of Eden. But it’s a head-scratcher of a tale, where nudity, curses and the perplexities of divine justice intertwine in a way that only the Old Testament can deliver.

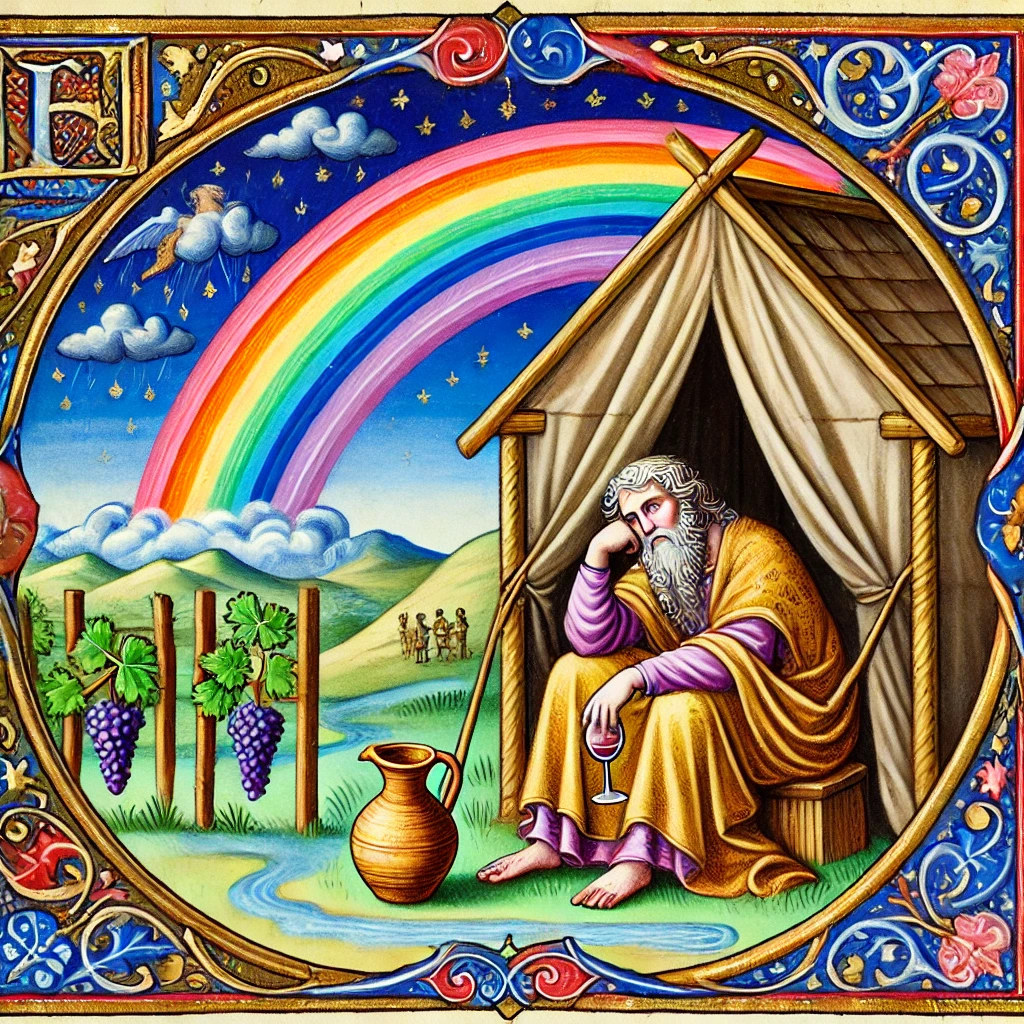

It begins in Genesis 9:20-27 with Noah, one of the few survivors of the Flood. Having planted a vineyard, he’s now enjoying a well-deserved drink after the harrowing events of the deluge. But this is no ordinary drink — he gets the first recorded hangover in history. Noah, in his post-apocalyptic revelry, indulges a bit too much and ends up sprawled naked in his tent. (Who hasn’t been there?) And this is when things take a bizarre turn.

“This isn’t the first or last time someone inadvertently witnessed a family member in an undressed state.

But in the world of the Old Testament, this act carries deep dishonor and disgrace.”

Noah survived the Flood, planted a vineyard, made wine, got wasted — and goes down in history as having the first recorded hangover.

RELATED: The Flood was a tale borrowed from another culture — and other controversial takes on Noah’s Ark and the Flood

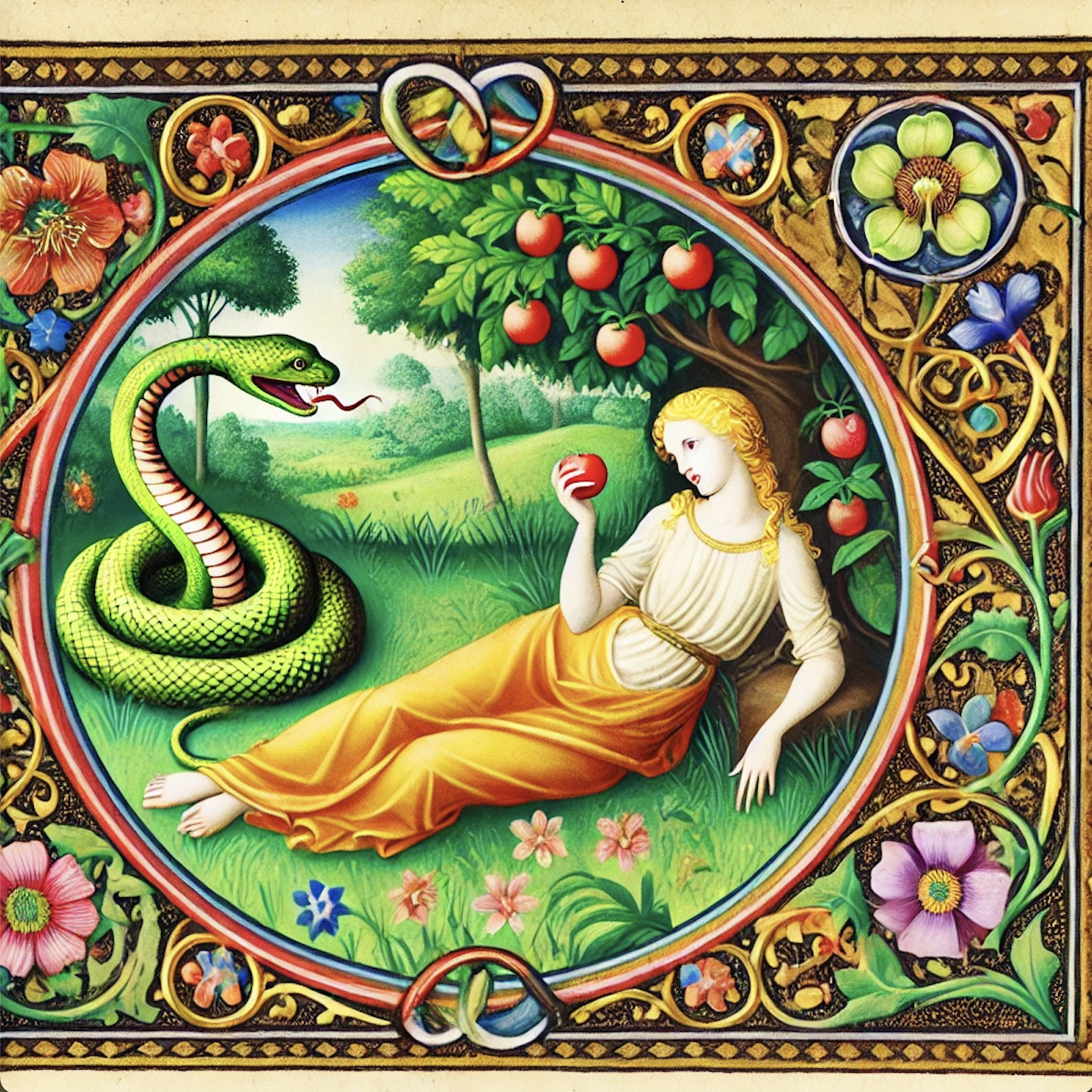

Enter Ham, Noah’s middle child. He stumbles upon his father in this compromising position and unwittingly does something that’ll echo through the generations: He sees Noah naked.

Ham stumbles upon his father naked — and all hell breaks loose.

The Indignity of Seeing Your Father Naked

Now, you might wonder, what’s the big deal? After all, this isn’t the first or last time someone inadvertently witnessed a family member in an undressed state. But in the world of the Old Testament, this act carries deep dishonor and disgrace.

The shame of nudity in this context isn’t just about physical exposure; it’s about a loss of dignity, a stripping away of the patriarch’s honor. Noah, as the father and leader, is supposed to be a figure of authority, respect and, perhaps most crucially, control. Seeing him naked, vulnerable and unconscious is a direct affront to this image. In the ancient world, where familial honor was paramount, this was akin to a serious breach of respect.

But Ham doesn’t just see his father naked — he goes and tells his brothers, Shem and Japheth, about it. Shem and Japheth respond by carefully covering their father, walking backward with a garment to ensure they don’t see his nakedness. This act of discretion starkly contrasts Ham’s behavior, which some interpretations suggest wasn’t an innocent blunder but perhaps a deliberate act of mockery or dishonor.

Good boys that they are, Shem and Japheth bring a sheet to cover their indecent father.

When Noah wakes up and discovers what Ham has done — or rather, what he’s seen — he doesn’t curse Ham directly but instead curses Ham’s son, Canaan: “Cursed be Canaan; the lowest of slaves will he be to his brothers” (Genesis 9:25).

Did Ham do more than just see his father passed out and naked?

Castration or Another Violation

Some scholars, like David M. Goldenberg, have explored the possibility that Ham’s offense was far graver than a mere glimpse of his father’s nakedness. Ancient Jewish interpretations suggest that Ham may have castrated Noah or even violated him, which would explain the severity of Noah’s reaction. Though these interpretations are speculative and highly debated, they attempt to rationalize why Noah’s curse was so intense.

Poor innocent Canaan didn’t do anything wrong — but ends up cursed.

Was this story written later to explain the subjugation of the Canaanites?

Cursing the Canaanites

But why did the curse fall on Canaan, Ham’s son? One theory, as suggested by scholars like Bernard Levinson, is that this curse was a later editorial choice, designed to provide a backstory for the subjugation of the Canaanites by the Israelites. By cursing Canaan, the text offers a divine justification for Israel’s later actions against these people, weaving the story into the sociopolitical realities of the time.

Noah curses Canaan and his descendants.

The Naked Truth?

This story has been the subject of numerous interpretations, many of them controversial. Throughout history, it’s been used to justify various social hierarchies and even slavery, though these takes are now widely criticized. The notion of cursing an entire lineage for the actions of one man is as perplexing as it is unsettling, and it’s one of those biblical moments that leaves us with more questions than answers.

The tale of Ham and the curse of Canaan is a cautionary tale about the weight of family honor, the repercussions of indiscretion, and the enduring power of curses. It’s a story that reminds us that even the most righteous among us, like Noah, are far from perfect — and that sometimes, the consequences of our actions can ripple through generations in ways we might never expect. –Wally