The Temple of Horus at Edfu, one of the best-preserved Greco-Roman sites in Egypt, can be paired with Kom Ombo.

The well-preserved Temple of Horus at Edfu is in the Ptolemaic style.

It’s no secret that Wally and I love temples and visited as many as we possibly could during our time in Egypt. Our favorites ended up being the less-busy ones, and the Temple of Horus at Edfu fell into this category.

Wally and Duke hired a driver and guide to take them from Aswan to Luxor, stopping at Kom Ombo and Edfu on the way up.

The city of Edfu and its Ptolemaic-period temple was about a two-hour drive from the Temple of Kom Ombo and sits on the West Bank of the Nile.

“The evil god Seth is shown in the form of a hippopotamus, his diminutive size rendering him less threatening.

Ancient Egyptians believed that what was carved was given life.”

In antiquity, Edfu was known as Behdet, and the region was referred to as Wetjeset-Hrw, “The Place Where Horus Is Extolled.” Local lore hypothesized that this was the site of the fierce and final battle between Horus, a falcon-headed god of the sky, and his wicked uncle, Seth, a jackal-headed god of chaos who killed Horus’ father Osiris. The modern Arabic name, Edfu, comes from the ancient Egyptian name Djeba, or Etbo in Coptic. Djeba means Retribution Town, this being where the enemies of Horus were brought to justice.

READ ABOUT THE CRAZY BATTLE OF THE GODS: Horus vs. Seth: Homosexuality, Hippos and Familial Violence

Construction on the Temple of Horus was started by Ptolemy III in 237 BCE, after the last native Egyptian pharaoh ruled. Its style combines classical Egyptian architectural elements with Greco-Roman influences. Work on the temple was frequently stalled due to insurrection — the Egyptians despised their new Ptolemaic rulers. It ultimately took six successive rules to complete, in 57 BCE.

The mammisi in front of the main temple at Edfu honors Harsomptus, the son of Horus and Hathor. The courtyard in front of smaller structure was the site of an annual festival of singing and dancing.

Et Tu, Edfu?

The site is one of the best-preserved pharaonic monuments, thanks to being almost completely buried in sand until French archaeologist Auguste Mariette stumbled across them and began excavating the ruins in 1860. At that time, the desert had swallowed the temple up to its lintels, and locals had built mud-brick dwellings on top of the hypostyle hall.

The Ptolemy rulers adopted Egyptian customs, including depicting themselves with the gods on the walls of temples.

Later generations of Coptic Christians had a bad habit of defiling imagery of the gods, which they viewed as blasphemous.

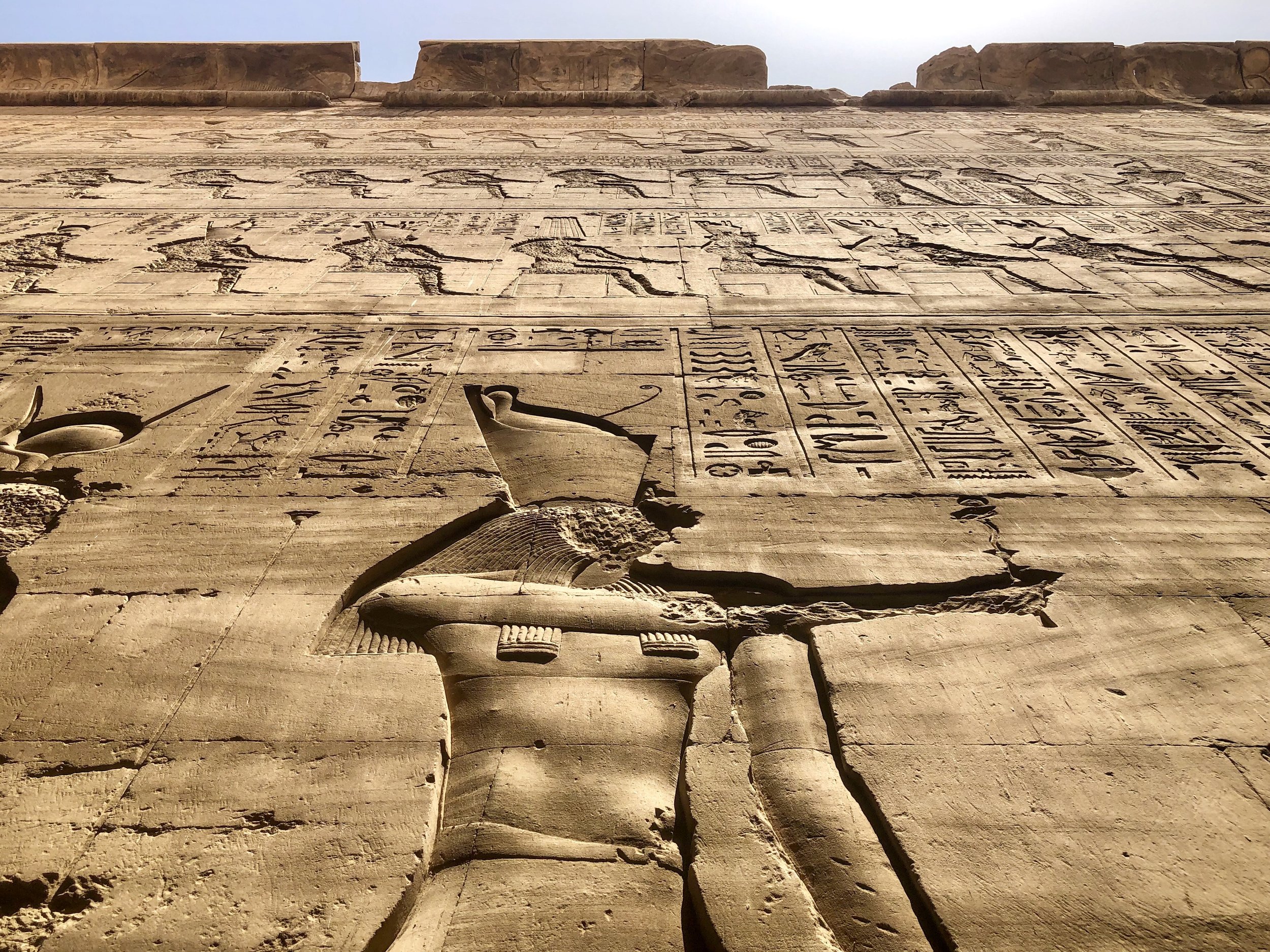

The focal point of the temple exterior is the entrance gate. Monumental in scale, the twin pylons measure an impressive 118 feet tall. The incised reliefs depict Ptolemy XII smiting his enemies before Horus. As this part of the structure was visible to the general public, and literacy levels were literally nonexistent — only an elite few could read and write hieroglyphics — imagery like this was used as propaganda to emphasize the might and legitimacy of the rulers.

Imagery on the pylon gates would have been visible to the public and served as propaganda to legitimize the Ptolemaic dynasty.

Wally stands with one of the giant falcon statues out front. They depict the god Horus, and the small person they’re protecting is none other than Caesarion, the son of Cleopatra and Julius Caesar.

Beyond the pylon is the court of offerings, a large paved terrace surrounded on three sides by a 32-columned arcade where the populace would bring their offerings to the statue of Horus.

Only elites could read and write hieroglyphics, so pictures told the story.

Adorning the walls are reliefs depicting the Feast of the Beautiful Meeting, the annual reunion between Horus and his wife, Hathor. The festival lasted 15 days from the arrival of the sacred cult image of the goddess, which traveled by sacred barge from Dendera to Edfu. The statues of the gods were reunited within the temple sanctuary, where Hathor was symbolically impregnated by Horus and returned to Dendera to bear their son Harsomptus.

This hieroglyph represents the people of Egypt — and looks quite a bit like the ba, one of the symbols of the body’s soul — or, as Duke thinks, a bird taking a selfie.

A glyph that I saw here, and at many of the other temples, looked like a bird holding a phone and taking a selfie. I asked our guide Mamduh (pronounced Mom-doo) what this was, and he told me that it’s actually a rekhyt, a lapwing bird that symbolically represented the common people of Egypt under the king’s rule. Its upraised human arms are not holding a phone but are instead a presenting a gesture of adoration. The symbol also acted as a boundary marker and designated where the populace was allowed to congregate and what parts of the temple were off limits.

This statue of an eagle honors Horus, who is usually depicted with the bird of prey’s head. Pharaohs aligned themselves with this deity.

Falcon Crest and Fatty

A 10-foot-tall black granite statue of Horus as a falcon wearing the double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt stood ahead of us outside the entrance to the outer hypostyle hall. The central doorway was originally fitted with cedar doors that were closed to the public. Stone screen walls, half the height of the front columns, still stand to either side and aided in further obscuring the view of the interior. Eighteen palmiform columns date to the reign of Ptolemy VIII, who was given the not-so-nice nickname Physkon, or Fatty, by his contemporaries. I would imagine the climate of Egypt did not prove agreeable to him.

This section of the temple was built by Pharaoh Fatty.

Wally felt the power of the holy temple.

We followed Mamduh into the second hypostyle hall, which is older and smaller than the first. The room was dim except for shafts of natural light that entered the chamber through small apertures cut into the roof. Mamduh paused to explain the significance of the 12 papyrus columns, which symbolize the concept of amduat, the nightly journey of the sun god Ra through the 12 regions of the netherworld, corresponding to each of the 12 hours of the night.

A chamber off the hypostyle hall depicts the process for making perfume.

Heaven Scent

Off to the side of the hall was a small chamber that Mamduh referred to as the laboratory. Piquing our interest, he went on to elaborate that temple priests used this particular room for making perfume and incense. He gestured to the ritual scenes and accompanying hieroglyphics, explaining that they contain ancient recipes and methods of preparation. Burned daily in the temple, ingredients included frankincense, myrrh, mastic, pine resin and spices such as cinnamon, cardamom, saffron, juniper and mint.

One of the Ptolemies honoring Horus

Seeking Sanctuary

The narrow room beyond the second hypostyle hall is the hall of offerings, where food and drink were consecrated daily for the eternal sustenance of the deity.

From there we entered the windowless holy of holies, which contains a granite shrine, the naos of Nectanebo II, the last of the native rulers of Egypt. This is the oldest and most sacred part of the temple and once held a golden cult statue of Horus. Nowadays, a reproduction of the god’s processional solar barque rests atop a low pedestal. The original is now in the Louvre.

During the Festival of the Beautiful Meeting, the statue of Horus was carried out of the sanctuary on a solar boat like this to reunite with his consort, Hathor, who traveled down the Nile from Dendera.

Chapels, storerooms and ancillary chambers dedicated to various deities, including Min, Sekhmet, Osiris, Khonsu, Hathor and Ra, are arranged around the central sanctuary.

Mamduh gave us a moment to backtrack and told us how the stairwell design mimics the spiraling circular path of a falcon’s ascent. Another stairwell, used to descend from the roof, is straight, to evoke a falcon’s downward plunge.

During the Opening of the Year festival, the equivalent of New Year’s Day, the cult statue of Horus was carried up the ascending staircase to the temple rooftop to bask in the first sunrise of the new year. The ritual is depicted in raised relief with figures of priests and bearers. Unfortunately, roof access is closed to visitors.

You’ll feel like Indiana Jones, exploring the dark passageways covered with amazing carvings.

We encountered a father and young daughter, who I believe were French from the few words I heard spoken between them. I’m not sure if it was due to excitement or boredom, but the girl ran away from her father. Later, we saw her wandering around the inner sanctum, lost, calling out to him. “Serves her right for being naughty,” Wally remarked.

The figure on the left pours out holy water in front of Horus.

Finally, we emerged outside in a narrow outer hall known as the Passage of Victory. Its walls are decorated with a tableau of scenes and texts depicting the Contendings of Horus and Seth. Seth is shown in the form of a hippopotamus, his diminutive size rendering him less threatening (Ancient Egyptians believed that what was carved was given life). Horus, casts his harpoon 10 times into Seth the hippo, ultimately conquering him and ascending the throne. Unfortunately, many of the carvings bear scars from chisels, obliterating the faces, hands and feet of gods — most likely the handiwork of Coptic Christians who found the images blasphemous.

The god Horus battles his Uncle Seth, who’s shown as a small hippo — Ancient Egyptians believed that if you carved something, it would actually happen. So they didn’t want to give too much power to the evil Seth.

Horus and Seth battle for the crown of Egypt, and Horus is ultimately victorious.

If you’re traveling to Luxor, consider heading down to Kom Ombo and Edfu. Admission to the Temple of Horus at Edfu costs 140 Egyptian pounds, or a bit over $8 when we visited. We booked through Egypt Sunset Tours, stopping at the two sites on a drive up from Aswan. You won’t get to see the ancient festival, but at least you can explore the entire temple, something only the most elite were allowed to do in antiquity. –Duke

Step back in time to explore the temple at Edfu, more than 2,200 years old!

The Temple of Horus at Edfu

Adfo

Markaz Edfo

Aswan Governorate

Egypt