Beware! Medusa, the Sphinx, Cerberus and other monsters reveal the greatest fears of a society.

Saint Martha Taming the Tarasque, circa 1500

There’s young Wally, curled up on the loveseat in the living room (the one his mother constantly tells him not to sit on), with D’Aulaires’ Book of Greek Myths or the D&D Monster Manual.

The original Monster Manual used to play Dungeons & Dragons

From an early age, I’ve always loved monsters. Of course I imagined myself as a hero, and that often entailed slaying monsters — usually with magic. But I always found something sympathetic about monsters. To me, they often seemed misunderstood and maligned. Yes, the Minotaur devoured innocent youths. But did he ask to be born a vicious half-breed, trapped in the Labyrinth?

The monsters of myth continue to have a mass appeal, as evidenced by the vampire craze (think True Blood, Twilight, Interview With the Vampire and The Vampire Diaries).

As my friend Heather’s little boy, Gulliver, explained to me about the Batman villain Two-Face, “He’s a likable baddie.” He paused, then continued, “He’s a baddie — but he’s a goodie to me.”

Couldn’t have said it better myself.

While scrolling though episodes of The History of Ancient Greece podcast, I was intrigued to see one that had an interview with Liz Gloyn, senior lecturer in Classics at Royal Holloway at the University of London and author of Tracking Classical Monsters in Popular Culture. Upon listening, I couldn’t help but wonder: Why didn’t my college offer courses on monster theory?!

Liz Gloyn, author of Tracking Classical Monsters in Popular Culture

I reached out to Dr. Gloyn, and she graciously agreed to answer some questions about monster theory and her obsession with things that go bump in the night. –Wally

What drew you to monsters in the first place?

To be perfectly honest, I got cross! I had come up with an idea about how the original Clash of the Titans film used monsters and wanted to read what people had said on this subject, but when I went to look at the existing literature, there was nothing there. I could have read all I wanted to on the representation of the famous Greek heroes — Perseus, Theseus, Hercules and the rest — but monsters got treated as if they were scenery. That didn’t make any sense to me, so after I had finished with the piece I wanted to write about Clash of the Titans, I decided it was time for the monsters to get some proper attention of their own.

The Italian movie poster for the original Clash of the Titans, which came out in 1981

“It’s noticeable how many monsters turn out to be women — or, if they’re male, they’re hypersexualized and hyperviolent, reflecting what happens without the controlling influence of civilization. ”

What is monster theory?

Monster theory is the field of academic studies which seeks to explain and understand the function of monsters. It’s based on a very influential piece by a medievalist, Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, who set out seven theses of monster culture, or seven ways in which monsters manifest and make themselves known.

Few could dream up creepy creatures like Hieronymus Bosch, who painted up horrorscapes in the late 1400s and early 1500s

Monster theory argues that monsters are cultural creations — that is, the particular fears and concerns of a given culture will generate monsters which reflect those fears and concerns. They might be about the “other,” whether you define that in terms of gender, sexuality, ethnicity or something else; they might be about behavioral taboos which need to be observed to keep society safe. And however hard a culture tries to banish a monster, it always comes back.

How has the perception of monsters changed over the years?

In the ancient world, monsters were very much known by how they looked — you could spot a monster a mile off, although it was also possible to bump into one by accident if you were wandering around the forest not paying attention.

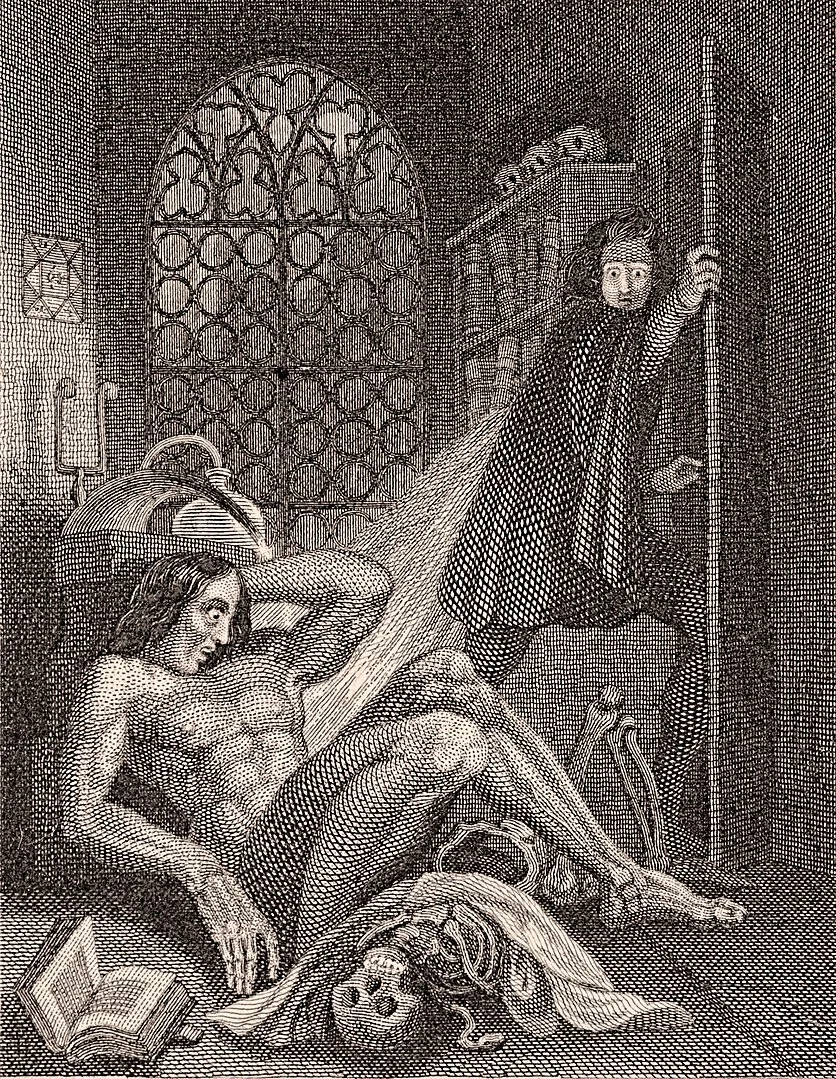

What we’ve seen since antiquity is a move away from a monstrous outside necessitating a monstrous inside. The break begins with Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, where the Creature is initially an innocent and only becomes monstrous when people treat him badly because of his appearance.

The frontispiece to an 1831 edition of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein

What we’re seeing in the 21st century is a major anxiety over not being able to spot a monster on sight — we fear things like the serial killer, the faceless evil government corporation and the imperceptible virus carrying a gruesome disease. That’s what makes the presence of classical monsters in popular culture even more interesting — they’re still immediately recognizable, and so out of step with more modern kinds of monstrosity, yet still have considerable appeal.

What’s the most surprising finding from your research on monsters?

I think what I’ve been most surprised by is the sheer range of modern interpretations of classical monsters out there. When people know you’re working on this stuff, they pass on every example that they come across, and some of the things that have been shared with me are really amazing: tattoos, bar signs, graffiti, as well as places you might expect to find them like computer games, films and books.

Dr. Gloyn didn’t know Wally has a Medusa tattoo — though she’d hardly be surprised

I’ve been particularly interested to find how popular Medusa tattoos are. As a monster that can turn people to stone with a glance, she’s not the most obvious thing to have permanently inked on your arm, but she’s clearly been a very important choice for a lot of people.

Head of Medusa by Peter Paul Rubens and Frans Snyders, circa 1618. Not too many people know that Medusa was a rape victim punished by being transformed into a monster

What monster has been most maligned in your opinion?

Historically, it does have to be Medusa — her origin myth as told to us by Ovid in his poem The Metamorphoses is pretty explicit that the transformation happens after Poseidon has raped her, specifically as a punishment from Athena.

When you hear Medusa’s story, you can’t help but feel some sympathy for her and be pleased that she’s such a badass, even after death

Ovid’s version has been the most read and most influential in post-classical cultures, but until recently Medusa’s rape was translated away as “seduction” or a similar euphemism. Thankfully, as Latin literature has been opened up to a wider audience and stopped being the province of elite white men, we’re starting to see more versions of the story which grapple with Medusa’s identity as a survivor of sexual violence, so that aspect of the myth is beginning to get the coverage it should have.

Centaurs were wild creatures hardly more civilized than the wild beasts attacking them in this mosaic

What does monster theory tell us about how women are perceived? Men? Any other groups?

Monster theory argues that monsters come into existence in order to help society articulate fears and concerns about people not belonging to the dominant group — so, given the social structures of patriarchy, it has quite a lot to say about how society monsters women! Particularly in Greek myth, it’s noticeable just how many monsters turn out to be women — or, if they’re male, like centaurs, they’re hypersexualized and hyperviolent, reflecting what happens without the controlling influence of civilization.

The Rape of Hippodamia by Peter Paul Rubens, 1638. Drunken centaurs tried to carry off the bride at her wedding feast

What looking at monsters that map on to different groups of people really tells us is what kind of threat they are supposed to hold. We see this, for instance, in the demonization of sexually active women in figures like the Sirens, or the way that villains in Hollywood are so often queer-coded, even in films made this century.

Every society and every time period will react to these threats differently, so while there are some patterns we can spot which repeat, each monster reflects back the particular concerns of the society that generated it.

The Victorious Sphinx by Gustave Moreau, 1886. You had only one chance to get the riddle of the Sphinx right

What’s your favorite monster, and why?

I have a soft spot for Medusa, as you may already have noticed, but I’m going to say the Sphinx.

Oedipus and the Sphinx by Gustave Moreau, 1864. The wandering hero solves the riddle, so upsetting the Sphinx, she kills herself

Before Oedipus shows up and solves her riddle, she has been patiently sitting on the road to Thebes, saying her piece to every passing traveller and then, when they don’t listen to her properly and instead try to mansplain her riddle to her, eating them. I admit that this might be a slightly free interpretation of the myth, but it does strike me that Oedipus solves the riddle because he’s the first person to actually pay attention to what the Sphinx is saying, as opposed to all her previous victims who just thought that they’d understood her.

Hercules and Cerberus by Peter Paul Rubens, 1637. Bad doggie! The three-headed pooch Cerberus guards the gates of Hell, but is caught by Hercules as one of his tasks

What monster would you least like to encounter?

Cerberus. I’m just not a dog person, let alone a three-headed dog person.