The sprawling temple complex in Luxor is considered one of the greatest architectural feats of all time.

Areas like this on the massive temple grounds of Karnak evoked Ancient Rome for Wally

For much of the history of Ancient Egypt, Karnak was the epicenter of worship, situated in the great city of Thebes (modern-day Luxor). Over 3,000 years ago, 30 or so pharaohs each wanted to put his or her stamp upon the temple, adding structures and elements, on and on through the centuries. In less-prosperous times, like the reign of Ramesses VI, the pharaoh simply recarved the additions made by his predecessor, Ramesses IV, and claimed them as his own. And Horemheb replaced King Tut’s name with his own on several monuments at Karnak, in a bid to sever all ties with the heretical lineage of Akhenaton.

The site sprawled, and today it is the largest surviving religious complex in the world.

“The great temple complex of Karnak was where Hatshepsut first started her genderbending iconography — all before she declared herself pharaoh.”

So much of Karnak as it is today began during the reign of that fascinating figure Hatshepsut, a female pharaoh who ruled during the 15th century BCE. Before her, Karnak was mostly mud brick but she embarked upon an ambitious construction program that included rebuilding Karnak with sandstone, making it more permanent and the basis of the massive complex we can still explore to this day.

The scale of these massive columns is difficult to describe without experiencing it yourself

Wally loves exploring ancient temples so much, he just had to jump for joy

I’ve mentioned before that a large part of the charm of visiting Egypt is that each temple has something utterly unique about it, and for Karnak it’s the massive scale of the site. In addition, because its stones were plundered for other construction projects, much of the complex lies in a semi-ruined state, which evoked Ancient Rome to me. It’s fun to clamber past large fragments of stone as you explore the temple.

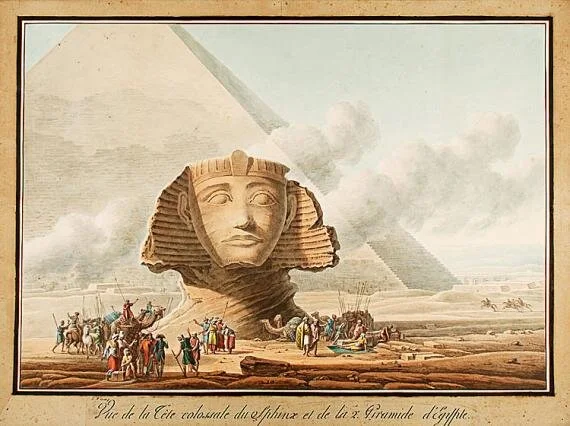

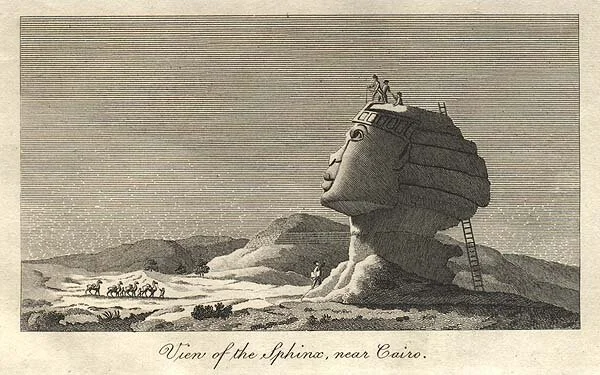

Rows of sphinxes welcome you to Karnak

A Tour of Karnak

We call the temple Karnak today, but that name came from a nearby village, el-Karnak. In ancient times it was known as Ipetisut, “the Most Select of Places.” The main part of the temple was dedicated to that great god, Amun (aka Amon, Amen), who was responsible for fertility and whom Egyptians trusted to keep their country prosperous.

Other, smaller, temples surrounded it, such as the one to Mut, the mother goddess and Amun’s consort.

Admission costs 150 Egyptian pounds, or less than $10, per person. You enter Karnak through an avenue of sphinxes bearing the heads of rams to honor Amun. Between each of their leonine paws, their chins resting on his head, stand small statues of Pharaoh Ramesses II, who commissioned the project.

Ram-headed, lion-bodied sphinxes protect diminutive statues of Ramesses II between their paws

Past these stone guardians, to the right, is a shrine to house the solar barque, used to transport the statue of the god during festivals. Built by Ramesses III, the exterior is lined with statues showing the pharaoh in mummy form with arms crossed to draw a connection with the god Osiris, ruler of the afterlife.

There’s much to explore at Karnak, so be sure to give yourself a couple of hours at least

The Great Hypostyle Hall

Pass under the Second Pylon to come to Karnak’s Great Hypostyle Hall, row upon rows of papyrus columns — 134, in fact. Unlike many other Ancient Egyptian temples, this colonnade is predominantly open-roofed. Blue sky can be seen above, and the sun blazes down upon you. Historians posit that this airy hall was the site of a ceremony called “uniting with the sun” and is supposed to resemble the primeval swamp, part of the creation myth.

The open-air nature of the Great Hypostyle Hall hints at the worship of Amun as a sun god

It’s near impossible to fully comprehend how gigantic some of these columns are, as you stand on the ground, gazing up. But the columns stand six stories high, and it’s said that some of the capitals, or tops, would fit 50 people!

An avenue of sphinxes once led all the way to Luxor Temple, two miles away — and there’s talk of restoring it

In ancient times, statues of deities would have been placed throughout this forest of columns. That’s one of the things that bummed me out most about these temples. As awesome as they are, most are devoid of statuary. I suppose they’ve been relocated to museums around the world — though I wish they had kept at least a few here and there.

That being said, Karnak is one of the few sites in Egypt where you’ll see quite a few statues on the grounds, though most are of pharaohs not gods.

You’ll spot quite a few statues as you wander Karnak

Pharaoh after pharaoh repurposed materials to rebuild portions of Karnak over the centuries

Reliefs cover the exterior of the hall, one showing Ramesses II’s Battle of Kadesh, which ended as a stalemate — though the pharaoh proclaimed victory. This was his favorite piece of revisionist history. He depicted his “triumph” at numerous temples, including Karnak, where he had a poem carved that told of his miraculous victory over the Hittites. His army was about to be defeated, but his father, the god Amun, made him invincible — and he single-handedly vanquished 2,500 of his enemies.

Hatshepsut depicted herself as a pharaoh blessed by the gods on one of her obelisks, now on its side by the Sacred Lake

The great temple complex of Karnak was where Hatshepsut first started her genderbending iconography. A carving shows her wearing a masculine wig and the atef crown, which sported ram’s horns and two feathers — all before she declared herself pharaoh.

It’s truly astounding that the Ancient Egyptians found a way to carve obelisks from a single stone and raise them, where they remain standing, thousands of years later

Obelisks: The Sun Made Stone

Obelisks were the most impressive of architectural feats. Carved from a single block of red granite, the top halves of them were covered in electrum, silver-gold sheets beaten flat. There was no stronger tie to the solar cult than these tall, thin structures resembling the sun’s rays, and, indeed, the metal caught the light, blinding onlookers.

One of the obelisks Hatshepsut erected at the site honors her patron deity, Amun, whom she once served as his “wife.” The inscription reads, in part: “I know that Karnak is Heaven on Earth, the sacred elevation of the first occasion, the eye of the Lord to the Limit, his favorite place, which bears his perfection and gathers his followers.”

Love among the ruins, Wally and Karnak style

A couple of obelisks tower above visitors to this day, and I’m not ashamed to say I was a little freaked out standing beneath them, imagining how easily they could become off-balanced and come crashing down upon us.

In fact, one obelisk does lie on its side, though it was probably done so purposefully. It’s on these remains, in front of the Sacred Lake, that you can see depictions of Hatshepsut as pharaoh.

No swimming allowed! The Sacred Lake was where priests would cleanse themselves before rituals

The Sacred Lake

The lake supplied Karnak with water, in part for its priests to cleanse themselves for rituals.

Nearby is a statue of a scarab (a word that sounds a whole lot cooler than “dung beetle”). Our guide Mamduh told us we should circle it three times for good luck, and a guy on Flickr complains: “Crazy tourists circumambulate — 3 times for luck, 7 times for love, and 10 times for wealth. Makes it hard to get a decent photo.”

Join the throng and walk in circles around the statue of Khepri, the scarab god, by the Sacred Lake. It’s said to be good luck

This is also where you’ll find a café, where we met up with our guide, smoking a cigarette and drinking coffee. He tried to convince us that hot beverages are better for your body in extreme heat, but we ignored his advice and went for ice-cold waters and ice cream treats.

Hatshepsut and Thutmose III make offerings to Amun in the carvings inside the Red Chapel

Hatshepsut’s Red Chapel

Egyptologists gush about Hatshepsut’s Red Chapel, but I don’t get it. To me, it’s not all that impressive, especially compared to all the other marvels found throughout the country, from massive colonnades to towering statues. It’s just a rectangular-shaped building.

Inside this deep red quartzite chapel in the heart of Karnak, Hatshepsut depicted herself as a male ruler. In fact, her images are difficult to tell apart from those of her nephew and co-pharaoh, Thutmose III.

Much like Hatshepsut’s, King Tut’s reign was stricken from the official record

After Hatshepsut’s death and toward the end of his reign, Thutmose III began a campaign to obliterate his co-ruler’s legacy. At Karnak, he took apart her sacred Red Chapel, leaving its bricks in rubble piles nearby. And at the Eighth Pylon, Thutmose III reassigned two colossal statues of Hatshepsut as pharaoh to his father, Thutmose II. The idea was to connect himself with the traditional patriarchal lineage — and hopefully have everyone forget the unconventional time he shared Egypt’s throne with a woman.

In 1997, the French Institute undertook the challenge of rebuilding what they refer to as la Chapelle Rouge. Today you can visit the Red Chapel, and hopefully you won’t have the space crowded with tourists and a woman doing an Instagram photo shoot out the back.

Beyond the Red Chapel, at the back of Karnak, off to the left, you can wander through Thutmose III’s Festival Hall.

Off to the side of the complex is the Akh-Menou, or Thutomose III’s Festival Hall, featuring tentpole columns

After exploring the rest of the complex, Duke and I wandered past the Sacred Lake, out to the Tenth Pylon. The gateway was closed off, but beyond was once an avenue of sphinxes that led to the Temple of Mut. The road took a turn and joined up with another avenue of sphinxes, this one leading all the way to Luxor Temple, two miles away. Everyone’s abuzz at the prospect of renovating and reopening that avenue — though it didn’t appear much progress had been made when we visited. –Wally

The temple grounds are a mishmash of architecture from many different pharaohs’ reigns

Much of Karnak lies in ruins

Hatshepsut built the Eighth Pylon, making it one of the oldest parts of the temple complex

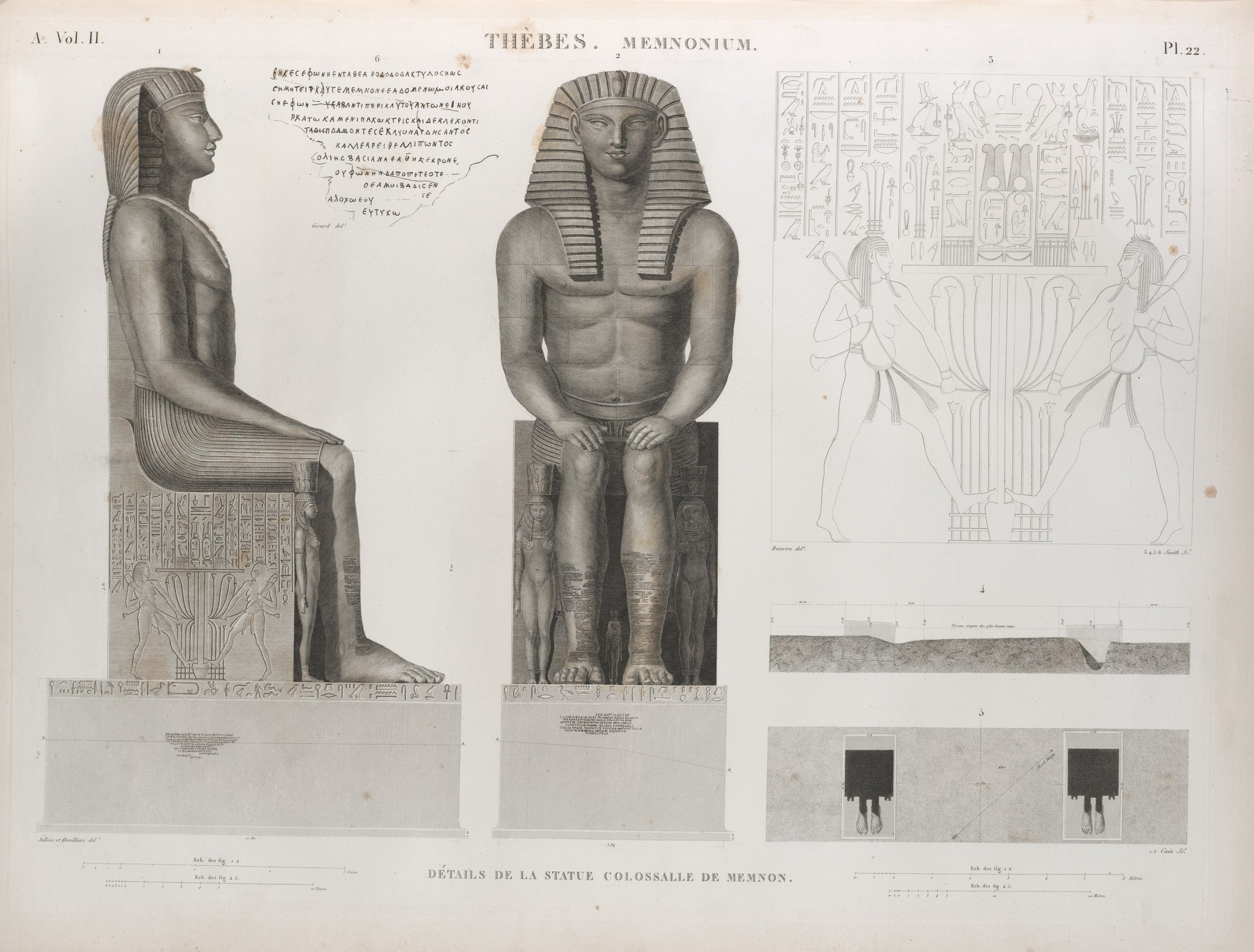

Historic renderings of Karnak

Even if you don’t read French, this map can help you navigate the Karnak complex