KV2 is a particularly fine example of these once-hidden burial chambers, where magic spells helped guide the pharaoh through the afterlife.

A glimpse into burial chamber of Ramesses IV

Arid, desolate and dusty, the colorless desert landscape of the Valley of the Kings belies the magic and mysticism hidden beneath in the tombs of the pharaohs.

Our early morning arrival allowed us to avoid some of the crowds, a welcome reprieve, as we’d travelled halfway around the world and didn’t want to share our trip with throngs of other tourists. And though the entrances to Egypt’s New Kingdom pharaohs’ burial chambers were intended to remain secret, they now dot the barren tract of land in every direction you look.

“Early explorers, such as Jean-François Champollion (who deciphered hieroglyphics using the Rosetta Stone), used the tomb as lodging during their time excavating the Valley of the KIngs.”

Wally near the tomb’s entrance

While visiting the site, your ticket includes admission for three tombs. Our guide, Mamduh, chose the tombs of Ramesses III, IV and IX — each of which is beautiful and unique in its own way.

We refer to many Egyptian pharaohs with Roman numerals like those of the kings of Europe. But, as Barbara Mertz points out in Temples, Tombs & Hieroglyphs, “such designations were never used by the Egyptians. (It’s easier to keep track of these fellows by such means than by trying to remember their distinctive throne names, which are often annoyingly similar and which were sometimes changed midreign.)”

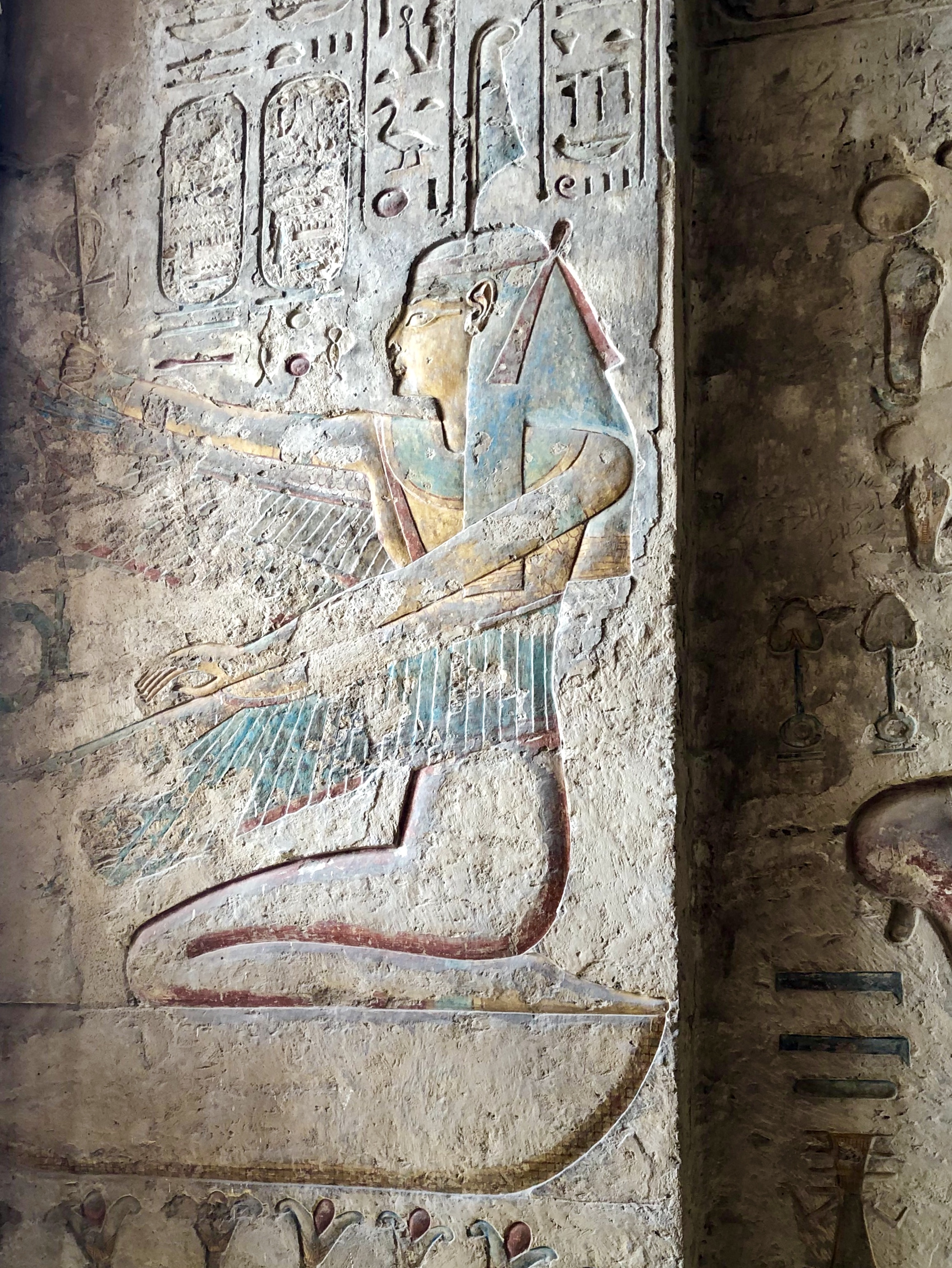

The pharaoh with the god Horus

Heqamaatre Ramesses, otherwise known as Ramesses IV, was the fifth and youngest son of Pharaoh Ramesses III. He was appointed crown prince by the 22nd year of his father’s reign, after his brothers had died — it wasn’t uncommon for people to die young in Ancient Egypt. With the assasination of his father in 1156 BCE, Ramesses IV, who was at this time middle-aged, inherited the throne. He died a mere six years into his reign.

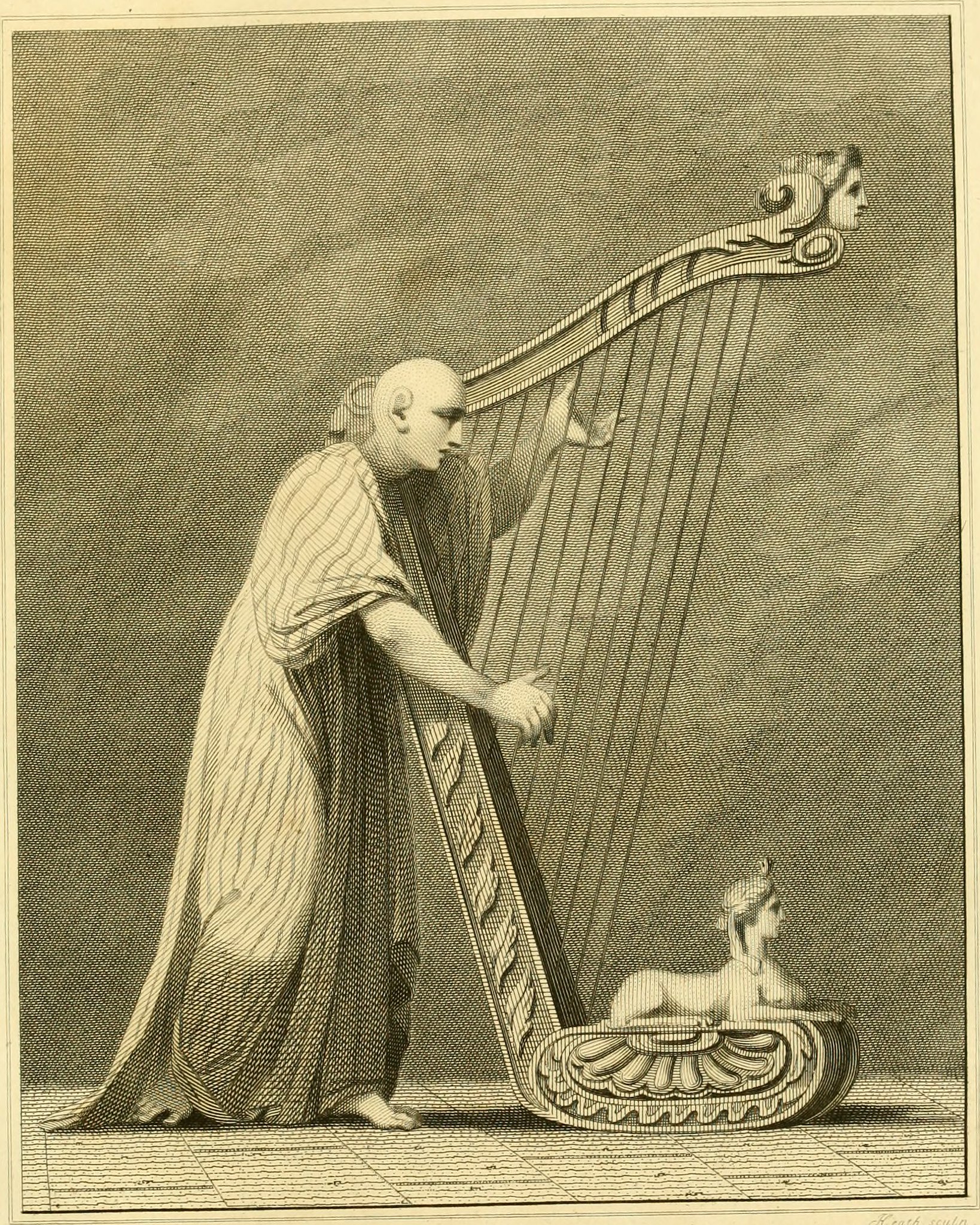

Magic spells line the walls of the tomb to guide Ramesses through the dangers of the afterlife

Passage to the Underworld

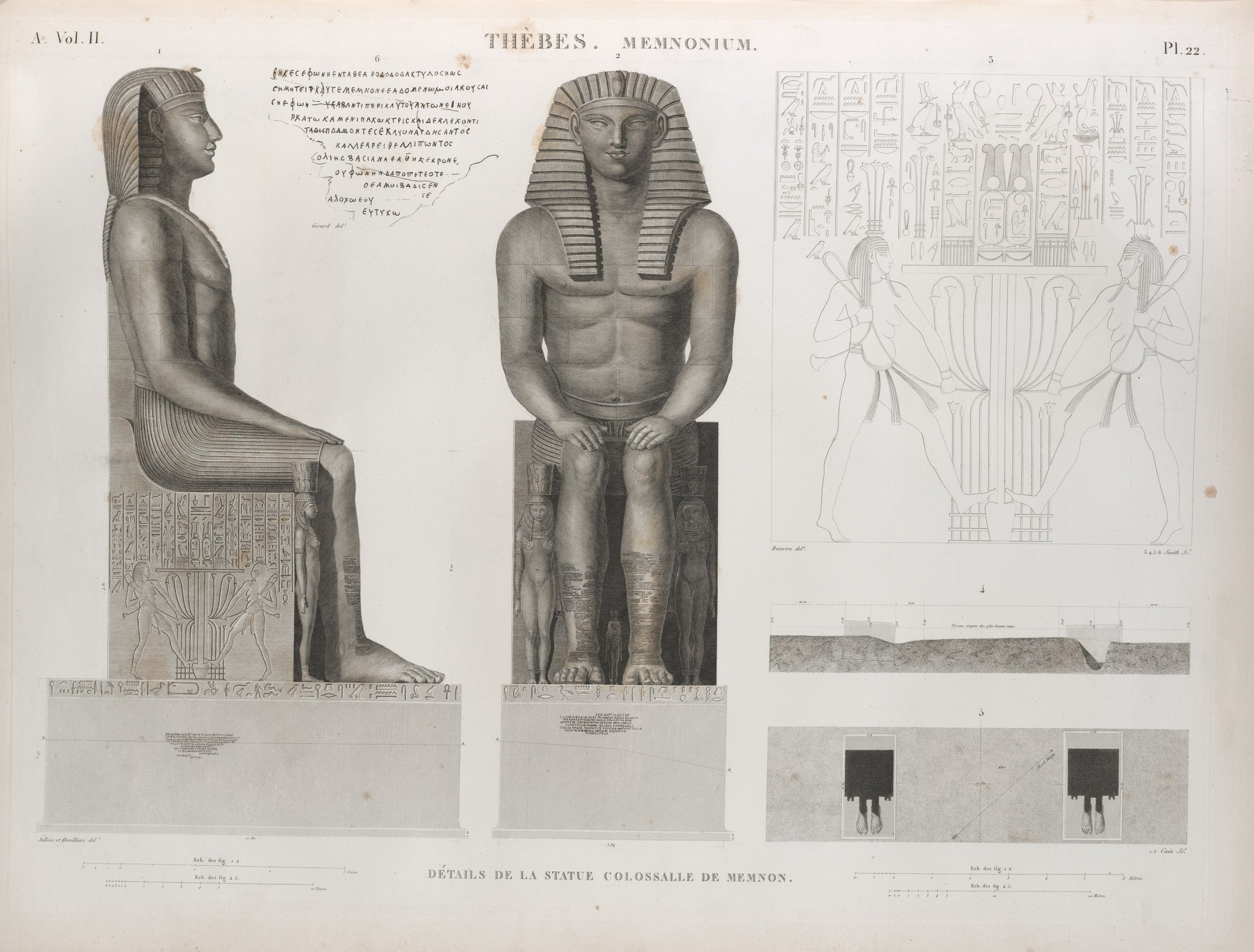

Each site in the Valley of the Kings now has a designator that begins with KV, for Kings’ Valley. Ramessess IV’s tomb is known as KV2 and has been open since antiquity. The area in front of the entranceway to the tomb was excavated by Edward Ayrton in 1905, and later by Howard Carter in 1920 (of King Tut fame). The archeological dig yielded a few relics, including shabti figures (which would act as servants in the afterlife) and glass and glazed earthenware pottery known as faience.

Early explorers, such as Jean-François Champollion (who deciphered hieroglyphics using the Rosetta Stone), Ippolito Rosellini and Theodore David, among others, used the tomb as lodging during their time excavating the valley.

The entryway has a staircase divided by a sloping central ramp that descends into a linear 292-foot-long passageway representing the symbolic journey of the sun god Ra (or Re). The tomb’s design is comprised of three corridors, an antechamber and a burial chamber with small annex chambers beyond. A large number of Coptic Christian and Roman graffiti can be seen scattered throughout the tomb, including prayers, drawings of crosses and saints. A particularly large inscription in red paint can be seen near the entrance to the tomb.

Those naughty Coptics defaced the walls near the entrance

Look for the red graffiti left by early Christians

Unlike other tombs from this era, KV2’s original design was modified: The chamber intended to be a pillared hall was converted to a burial chamber when the king died sooner than expected. Ramesses IV had doubled the workforce on the project to speed it along, but no one can stop death from coming — even a deified ruler.

A pair of rectangular niches set high into the walls at the front of the second corridor are decorated with manifestations of Ra. These figures continue as a register above the texts of the Litany of Re, which cover both walls of this corridor. The detailed carvings remain vibrant, despite the age of the tomb.

Look up to see stars painted on the ceiling

Seeing Stars

The third corridor contains a vaulted ceiling decorated with scenes from the funerary text the Book of Caverns. Although no well shaft was ever cut, a descending ramp passes through the antechamber and ends at the burial chamber’s entrance. Surrounded by golden stars on a blue background, the king’s names follow the path of the sun — the pharaoh and Ra had become one.

The paint is surprisingly bright, considering it’s millennia old

The massive stone sarcophagus would have housed at least two coffins like nesting dolls

Sometimes You Feel Like a Nut

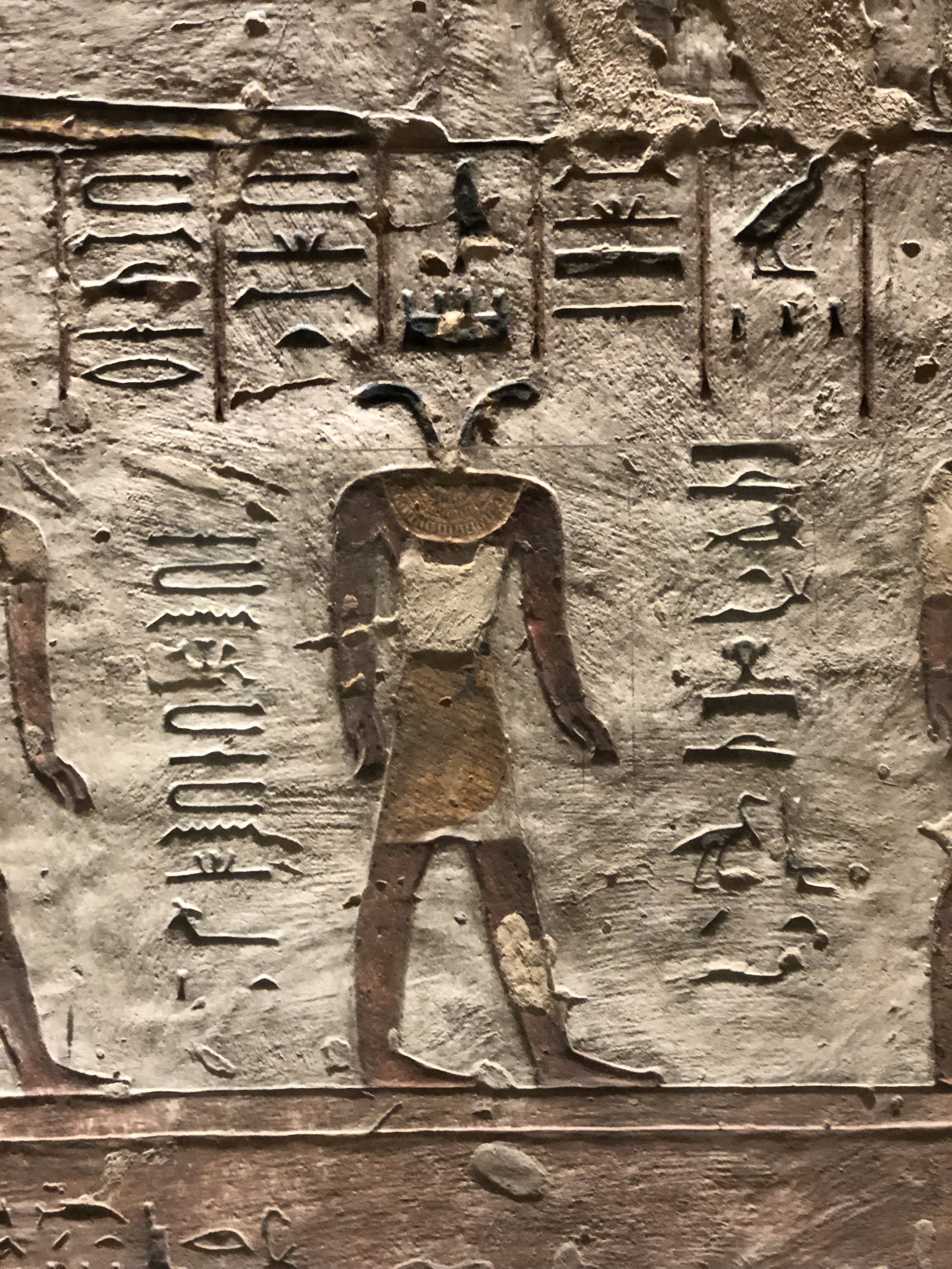

In the burial chamber, scenes from the Book of Gates show towering gateways that separate the divisions of the underworld guarded by fire-spitting serpents. Illustrations from other funerary texts, including the Amduat and the Book of Heavens, were inscribed on the ceiling of the sarcophagus chamber, depicting Ra’s nightly journey through the underworld.

Watch out for snakes! A depiction of what we can expect in death

Scenes from funerary texts were carved onto the walls of the tomb

Cobras and Anubis, a jackal-headed god of death

Ancient Egyptians believed that paintings could come to life — no need to bury servants alive; just draw them on the wall!

The burial chamber is almost filled by the massive quartzite sarcophagus. Twin figures of the sky goddess Nut are depicted on the ceiling, her elastic, naked body held aloft by her father Shu, the god of air and sunlight. Nut’s arms and legs extend downward to touch the horizon. Each night she swallows the sun disk, which travels through her body and emerges in the form of a winged scarab from her womb in the morning.

Ramesses IV’s tomb is an impressive example of New Kingdom burial chambers — though I’m not sure I’d want to have a slumber party in there like all those archaeologists. –Duke

You get to choose three tombs to visit with your pass